Kawasaki disease, first described in 1967, is an acute, self-limiting, febrile vasculitis that predominantly affects children under the age of 5 years.1 Treatment comprises primarily aspirin and intravenous immunoglobulin, along with corticosteroids, infliximab, other immunosuppressants and adjunctive plasmapheresis for refractory cases. Even with treatment, cardiovascular complications may arise, including coronary artery dilatation, valvular lesions, pericarditis and myocarditis.2 Patients who do not fulfil four of the five principal clinical features of Kawasaki disease, but are found to have coronary artery abnormalities, are deemed to have Kawasaki disease, albeit an incomplete form.

Almost all deaths in patients with Kawasaki disease result from its cardiovascular sequelae.3 Coronary artery dilation may progress to the formation of coronary aneurysms, which may persist into adulthood and carry an increased risk of death, MI and the need for coronary revascularisation.4 Even if coronary artery lesions eventually regress, the underlying tissue is not normal, and people diagnosed with these lesions have an increased lifetime risk of cardiac events.5

There are limited published clinical guidelines on the management and long-term follow-up of coronary artery disease in adults with late complications of Kawasaki disease. Therefore, the Asian Pacific Society of Cardiology (APSC) developed these consensus recommendations to provide expert guidance. These recommendations are intended to guide cardiologists and internists managing cardiovascular conditions. However, the consensus recommendations are meant to supplement – but not replace – clinical judgement.

Methods

The APSC convened a 12-member panel to review the existing literature, discuss gaps in the current management strategies, outline areas where further guidance is needed and – ultimately – develop consensus recommendations on the follow up and management of late coronary artery sequelae resulting from Kawasaki disease. The experts were mostly members of the APSC who were nominated by national societies and endorsed by the APSC consensus board, as well as international experts in treating coronary artery aneurysms. These consensus recommendations build on previous work by the American Heart Association and the Japanese Circulation Society (JCS)/Japanese Society for Cardiovascular Surgery.2,6

Consensus recommendations were developed by a process similar to that outlined in the 2019 American College of Cardiology methodology for creating expert consensus decision pathways.7 Draft consensus recommendations were developed based on the existing literature around the management of coronary sequelae of Kawasaki disease and circulated to the expert panel. Recommendations were discussed in a consensus meeting held on 11 May 2022. The statements were then each put to an independent online vote using a three-point scale (agree, neutral, or disagree). Consensus was reached when 80% of experts voted agree or neutral.

When there was no consensus, the statements were further discussed via email then revised accordingly until the criteria for consensus were reached.

Experts also reviewed the existing literature and appraised the evidence behind each consensus statement using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation system as follows:

- High (authors have high confidence that the true effect is similar to the estimated effect).

- Moderate (authors believe that the true effect is probably close to the estimated effect).

- Low (true effect may be markedly different from the estimated effect).

- Very low (true effect is probably markedly different from the estimated effect).

Consensus Recommendations

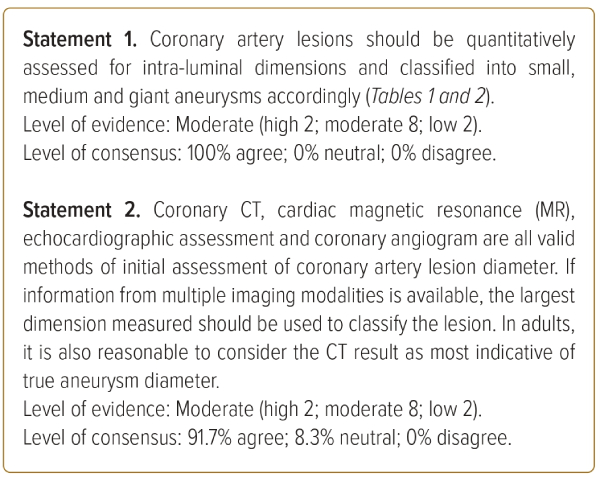

Assessment and Risk Stratification of Coronary Artery Lesions

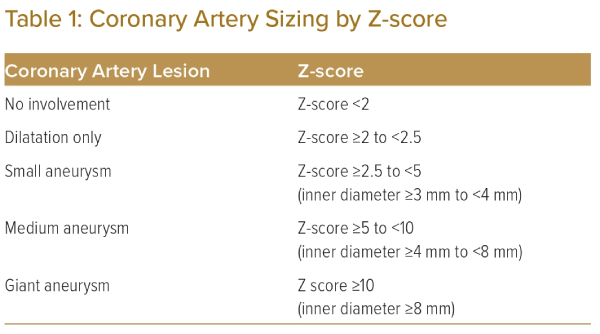

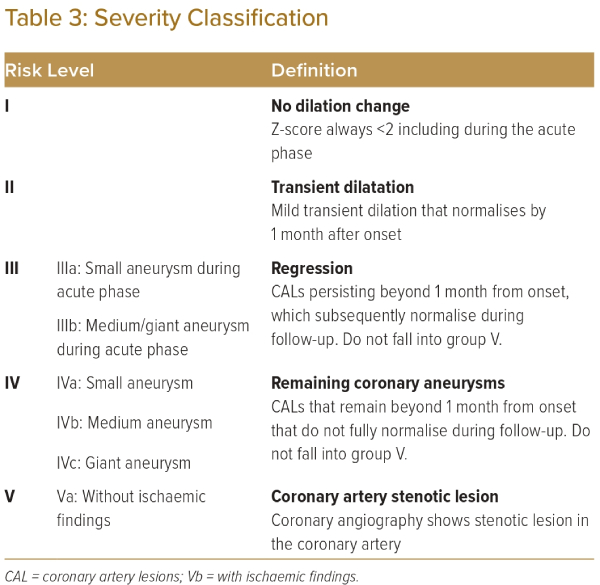

The initial classification of coronary artery lesions is important because it has prognostic relevance for subsequent outcomes.4,8 The presence and size of the coronary artery lesions are the most important factors for judging severity of Kawasaki disease. The JCS/JSCS 2020 guidelines suggest the use of the Z-score for evaluating the severity of coronary artery lesions by their intra-luminal diameter.6 Use of the Z-score is strongly recommended for patients aged ≥5 years (Table 1).2,6,9,10

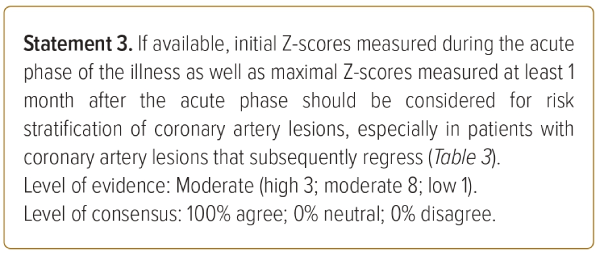

However, the JCS/JSCS 2020 guidelines on this relate primarily to children, and different formulae exist.2,6 In adults, there will patients in whom a normal segment may be ≥4 mm. Furthermore, the calculation of Z-scores in adults can be complicated and not practical for routine clinical practice. We propose the use of the alternative definition in the 2013 JCS guidelines, as indicated in Table 2.11 While the 2013 guidelines also apply to children, it can be more pragmatically applied to adults, as coronary artery aneurysms are sized relative to adjacent segments.

We also recognise that the absolute cut-off of 8 mm remains a useful reference point in defining giant aneurysms in the paediatric population, even if it may not be as significant in an adult population in which coronary arteries are naturally expected to be of larger diameter. Hence, while using the pragmatic method of classifying coronary aneurysms, we suggest that coronary artery aneurysms identified as ≥8 mm during assessment in childhood/teenage years retain the label of giant aneurysm into adulthood, unless they undergo significant regression.

It should be noted that other authors define coronary aneurysms as focal dilations of at least 1.5 times the adjacent normal segment.12–15 Furthermore, it has also been highlighted that a standard definition of ‘giant aneurysm’ does not exist.16 In the broader literature, the term ‘giant aneurysm’ has been accorded to aneurysms >20 mm, and this is used for aneurysms regardless of the underlying pathophysiology or cause.12,16 These discrepancies between aneurysms in general, and aneurysms arising from Kawasaki disease, should be acknowledged as an area of uncertainty.

In asymptomatic patients known to have a prior history of Kawasaki disease, coronary CT, cardiac MR, echocardiography and angiography are all valid imaging modalities to screen for remaining coronary artery lesions. The choice of imaging tool should consider the patient’s age and clinical characteristics, along with the availability of hardware and expertise in treating centres.

We recognise that each of these tools has its limitations. We also acknowledge that measurements of coronary artery lesion diameter may be complicated by calcification in the aneurysm wall. When amalgamating information from multiple imaging modalities, we suggest using the largest dimension measured to classify the coronary artery lesion. In adults, it is also reasonable to consider the CT scan result as indicative of true aneurysm diameter.

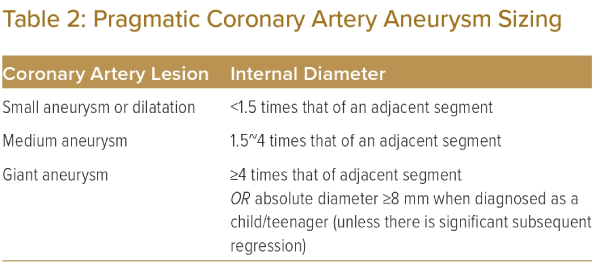

When available from childhood records, the initial Z-scores measured during the acute phase of the illness, as well as the maximal Z-score measured at least 1 month after the acute phase, should be considered in the risk stratification of coronary artery lesions. This has particular implications for patients in groups II or III (Table 3), where the previous presence of aneurysmal lesions that persist more than a month after the acute phase (as opposed to transient dilatation that resolves within a month) should prompt closer initial follow-up, even if the lesions do subsequently regress.2,6 For selected patients, additional invasive investigation with coronary angiography may be considered to diagnose stenotic lesions within aneurysmal segment and assess for ischaemic consequences via measurement of fractional flow reserve (FFR). This classification informs the risk of long-term sequelae, such as ischaemic heart disease caused by these coronary artery lesions.5,17,18 It will also be used to guide follow-up and management.

Long-term Follow-up of Coronary Artery Lesions

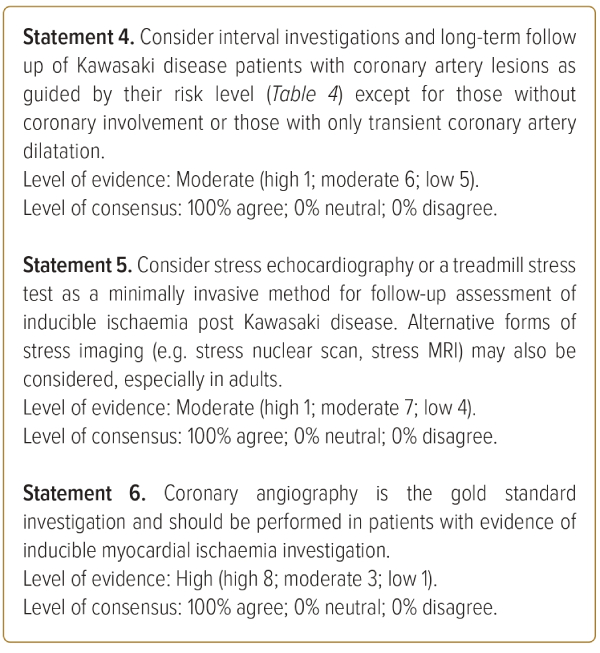

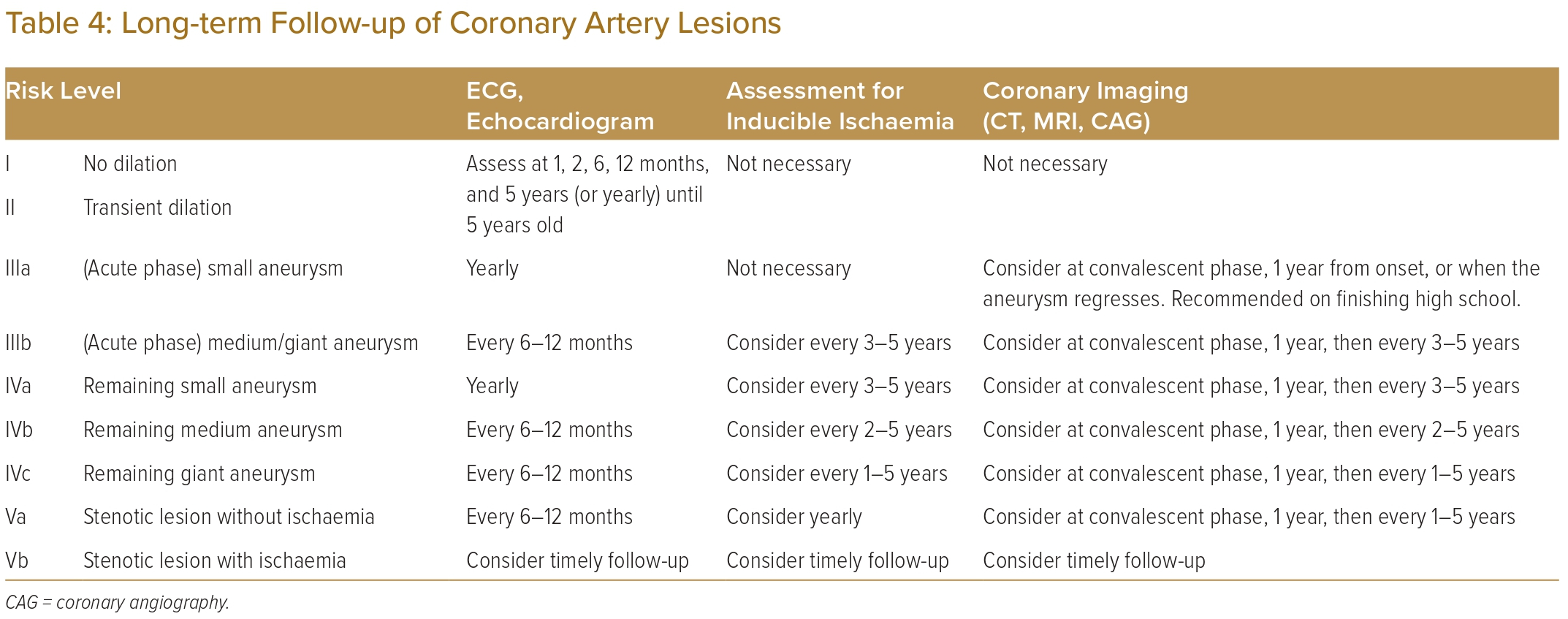

Follow-up for patients with coronary artery sequelae of Kawasaki disease should continue long-term, with interval evaluations for inducible ischaemia as well as consideration of re-imaging the coronary arteries.2,6 The degree of follow up should be guided by each patient’s risk level (Table 4).

Patients with transient dilation can be discharged from on-going cardiology care after follow-up for 5 years if luminal dimensions return to normal by 1 month.6 This should be clarified against aneurysms that have regressed. For regressed aneurysms, it is reasonable to follow up on Kawasaki disease patients even in the long term because of potential coronary events in adulthood and the functional and structural abnormalities in the coronary vessel wall in the long-term.19–21

Nevertheless, all patients should be reminded that having had Kawasaki disease is part of their permanent medical history and should be highlighted to medical professionals in the future. They should be counselled on general cardiovascular health and risk factors, including leading a healthy lifestyle.

Patients with medium or giant aneurysms in the acute phase, as well as all those with remnant aneurysmal coronary artery lesions, should receive regular assessments for inducible ischaemia. Stress echocardiography or treadmill stress tests should be considered as minimally invasive means of assessing for inducible ischaemia.22–25 Alternative forms of minimally invasive stress imaging, for example, stress nuclear scans or stress MRI, may also be considered, especially in adults.

There are additional considerations in children pertaining to these alternative imaging modalities. CT angiography provides a valuable non-invasive method of assessing coronary arteries, and a CT-derived FFR value can also be calculated, but it requires pharmacological control of heart rate and IV contrast use, as well as the risk of radiation exposure. Myocardial perfusion imaging is sensitive and useful for detecting myocardial ischaemia but carries the risk of radiation and the risk of drug load needed to provide myocardial stress. Cardiac MRI uses no radiation, but requires control of heart rate. It also has a long imaging duration, thus requiring a long sedation time.

In patients where an initial minimally invasive assessment reveals evidence of inducible myocardial ischaemia, coronary angiography should be performed. This enables detailed imaging of the coronary artery lumen and is the gold standard for evaluating the degree of stenosis, prognosticating the lesion and deciding if therapeutic intervention is indicated.26–28 Patients with stenotic lesions that are functionally significant and cause myocardial ischaemia (Table 4, group Vb) require closer attention and follow up. Hence, we suggest that the treating clinician exercises discretion in deciding the interval for follow-up investigations.

Medical Therapy for Coronary Artery Lesions

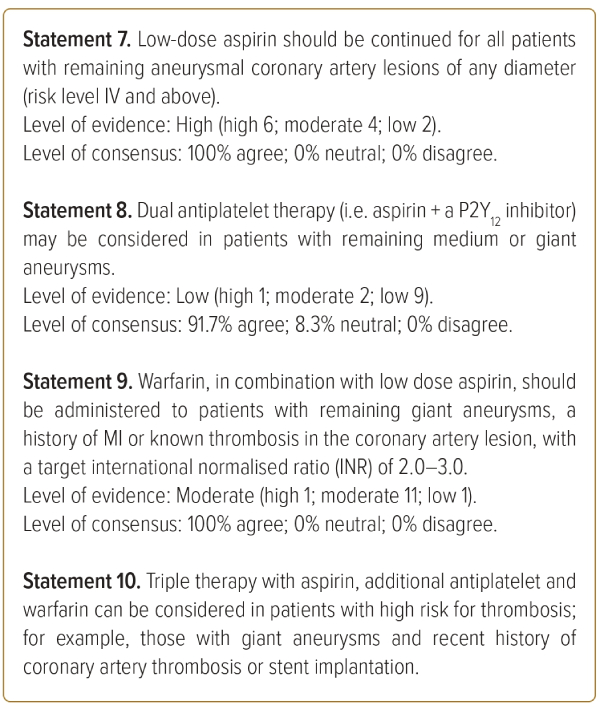

Aspirin is already well established as standard therapy in acute treatment of Kawasaki disease.29,30 We suggest that low-dose aspirin should be continued as primary prophylaxis against ischaemic heart disease in patients with remaining aneurysmal segments (risk level IV and above).2,6,31

Alternative antiplatelet agents should be considered for patients with resistance to aspirin or aspirin intolerance. In patients with remnant medium or giant aneurysms, dual antiplatelet therapy comprising aspirin plus another P2Y12 inhibitor may be considered.

Patients with remaining giant aneurysms, a history of MI or known thrombosis in the coronary artery lesion should be anticoagulated with warfarin in addition to low-dose aspirin, with a target INR of 2.0–3.0. Warfarin therapy, in combination with aspirin, has been shown to lower the incidence of MI as compared to aspirin alone.32,33 Target INR should take into consideration size of the aneurysm, clinical condition as well as the patient’s bleeding risk, with a lower target INR of 2.0–2.5 in patients with higher bleeding risk. Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is a reasonable alternative for patients who are unable to achieve a stable level of anticoagulation on warfarin.34

DOACs are a relatively new class of drugs, and there are limited data pertaining to their use in anticoagulation of giant aneurysms resulting from Kawasaki disease. Nonetheless, given the body of evidence around their use in other indications for anticoagulation, such as AF, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism and LV thrombus, they may be considered as an alternative anticoagulant to replace warfarin in the recommendations above.

Triple therapy with aspirin, an additional antiplatelet and warfarin can be considered in patients with high risk for thrombosis, such as those with giant aneurysms and recent history of coronary artery thrombosis or stent implantation.2,31 This can be continued for a short period of time, in line with other guidelines concerning stent implantation in patients with a separate indication for anticoagulation.35

Finally, there is some suggestion that statins may have a role in reducing coronary artery inflammation via their pleiotropic effects.36 Statins may thus be considered as adjunctive medical therapy in patients with remaining coronary artery lesions of any size.

Invasive Therapy for Coronary Artery Lesions

Coronary artery lesions with functionally significant stenosis may require emergent or elective intervention. In acute MI, we recommend considering primary PCI as the primary modality of reperfusion therapy to reperfuse the ischaemic myocardium as quickly as possible. Because data are limited, management is generally extrapolated from guidelines on management of acute coronary syndrome in adults. Intracoronary thrombolysis or intravenous antiplatelet agents (e.g. abciximab, eptifibatide and tirofiban) can be considered in patients with high thrombus burden within coronary aneurysms. Intracoronary thrombolysis has been shown to be effective in reducing thrombus burden in coronary aneurysms, even up to several hours after thrombus formation, although evidence is limited to case series.37–39

During coronary artery intervention, it is crucial to obtain an accurate picture of true luminal dimensions to guide balloon and stent sizing. Existing literature and clinical experience suggest that it is easy to underestimate true luminal dimensions and miss underlying aneurysmal distortion.40 We recommend the use of IVUS or OCT in the assessment of luminal dimensions.41–44

Chronic lesions are heavily fibrotic and calcified and may be difficult to expand by balloon angioplasty alone. Even if the lesion can be expanded, there is significant recoil, which limits the subsequent results. The high pressures needed to expand the lesions have been associated with formation of neo-aneurysms at the site of dilation.40,43

As such, while POBA may be effective for localised stenotic lesions without calcifications or aneurysms, less than a few years after the onset of Kawasaki disease, we do not recommend them in severely calcified chronic lesions. These may instead require rotational or orbital atherectomy or other adjunctive therapies (e.g. shockwave).43–46 In target vessels in which a burr larger than 2.15 mm in diameter can be used, good patency of the vessel can be maintained by close follow-up and repeat coronary rotational atherectomy, if required.46

CABG has been shown to be an effective method of revascularisation in the paediatric Kawasaki disease population, with good long-term outcomes.47–49 We recommend considering CABG for revascularisation of chronic coronary artery lesions in adults in accordance with other established guidelines in the literature for standard types of coronary artery disease.

Limitations and Future Research

There are significant limitations to these consensus statements. Kawasaki disease is a rare condition, and the prevalence of coronary sequelae has been steadily declining with improvements in diagnosis of Kawasaki disease as well as the introduction of aspirin and intravenous immunoglobulin as effective therapies in the acute phase. As such, evidence for some of these recommendations (in particular, Statements 9, 11, 12 and 13) are extrapolated from conventional adult coronary artery disease guidelines or based on case series with limited patients, some of which were published more than two decades ago.

There is currently no published evidence for the use of DOACs in the anticoagulation of Kawasaki disease patients with high-risk coronary lesions, and these recommendations are extrapolated from the use of DOACs in place of warfarin or LMWH for other indications. Ultimately, in this rare condition, treatment decisions should be individualised and determined by the managing physician with consideration for the patient’s unique profile. These consensus recommendations are meant to serve merely as a guide and not replace clinical judgement.

Further research is needed to determine the optimal medical therapy of remnant coronary artery lesions post Kawasaki disease, specifically, which combinations of antiplatelets/anticoagulation are most efficacious in the prevention of ischaemic heart disease while balanced against bleeding risks at each level of risk.

Conclusion

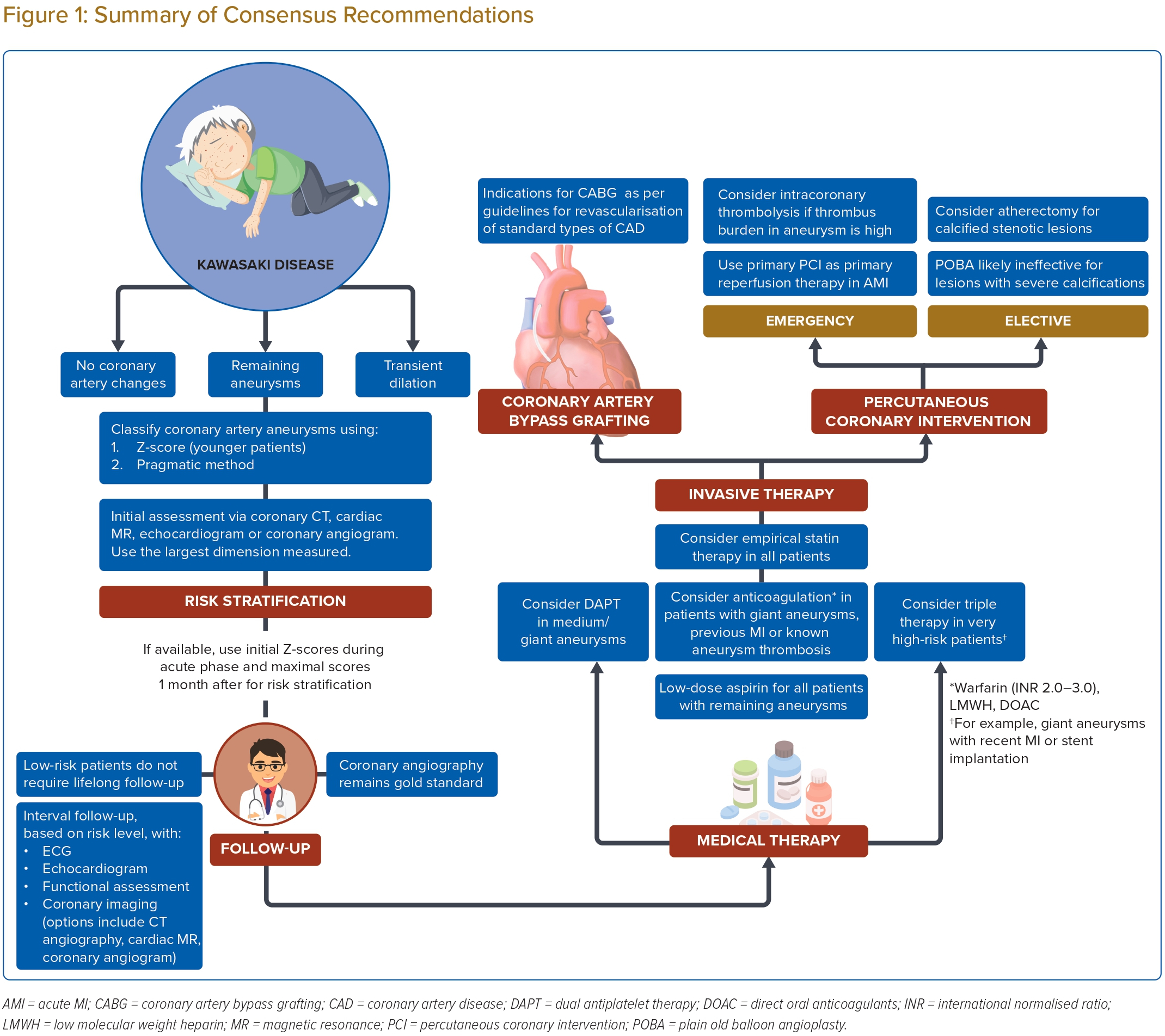

A summary of the consensus recommendations is shown in Figure 1. Advances in the management of Kawasaki disease have significantly reduced its mortality. Nevertheless, a proportion of patients may have residual coronary artery aneurysms that do not regress after the acute illness, which increases the risk of MI. We have developed these consensus recommendations to guide risk stratification, long-term follow up and management of coronary artery disease in adults with these late complications of Kawasaki disease.

Clinical Perspective

- Coronary artery lesions resulting from Kawasaki disease should be assessed for their intra-luminal dimensions and risk stratified accordingly.

- Risk level guides choice of investigations and intensity of long-term follow-up.

- Medical management for coronary artery lesions includes aspirin and statin, along with additional antiplatelet agents and/or anticoagulation in higher-risk patients.

- Primary percutaneous coronary intervention should be considered as primary reperfusion therapy in acute MI, with consideration of intracoronary thrombolysis or intravenous antiplatelet if the thrombus burden is high.

- During intervention, the use of intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography for accurate luminal sizing and atherectomy for calcified lesions should be considered.