Stenosis of the left main coronary artery (LMCA) is associated with significant mortality and morbidity because of the large area of affected myocardium.1,2 The Asia-Pacific Left Main ST-Elevation Registry found that MI due to LMCA stenosis (LM stenosis) is associated with high inhospital mortality and heart failure. Furthermore, survivors remain at high risk for adverse outcomes.3 Other studies have reported that, compared with white patients, Asian patients with LM stenosis have a lower body size, smaller lumen area, larger vessel area and larger plaque burden at the minimum lumen site and over the entire length of the LMCA. In contrast, white patients have more calcification compared with Asian patients.4

Evidence on the use of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in LM stenosis in Asia is growing, but anatomical variations and substantial heterogeneity in healthcare resources and infrastructure have contributed to a lack of consensus on the optimal management in the Asia-Pacific region.3 Hence, the Asian Pacific Society of Cardiology (APSC) developed these consensus recommendations on the appropriate use of PCI in the management of LM stenosis. These consensus statements were developed with general cardiologists and internal medicine specialists practising cardiology as the intended readers to guide them on the appropriate evaluation, treatment strategy selection, stenting strategy planning and the use of antiplatelet therapy in patients with LM stenosis.

Methods

The APSC convened an expert consensus panel to review the literature on the management of LM stenosis, discuss gaps in current management, determine areas where further guidance is needed and develop consensus recommendations on the assessment, management and referral of patients with LM stenosis. The 38 experts on the panel are members of the APSC who were nominated by national societies and endorsed by the APSC consensus board or invited international experts.

After a comprehensive literature search, selected applicable articles were reviewed and appraised using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation system.5 Based on this system, the level of evidence was designated as follows:

- High (authors have high confidence that the true effect is similar to the estimated effect).

- Moderate (authors believe that the true effect is probably close to the estimated effect).

- Low (true effect might be markedly different from the estimated effect).

- Very low (true effect is probably markedly different from the estimated effect).

As indicated in these levels, the authors adjusted the level of evidence if the estimated effect, when applied in the Asia-Pacific region, may differ from the published evidence because of various factors such as ethnicity, cultural differences and/or healthcare systems and resources.

The available evidence was then discussed and consensus recommendations were developed during a virtual consensus meeting in September 2023, a face-to-face meeting in October 2023, and email correspondence from November 2023 to January 2024. The final consensus statements were then put to an online vote, with each recommendation being voted on by each panel member using a threepoint scale (i.e., agree, neutral, or disagree). Consensus was reached when 80% of votes for a recommendation were agree or neutral. In the case of non-consensus, the recommendations were further discussed using email communication then revised accordingly until the criteria for consensus were fulfilled.

Consensus Recommendations

Imaging of Left Main Coronary Artery Stenosis

Statement 1. Intravascular imaging or physiological testing is recommended to further assess LM stenosis with intermediate (50– 70%) diameter stenosis.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of consensus: 100% agree; 0% neutral; 0% disagree.

Statement 2. A minimum lumen area (MLA) of ≤4.5 mm2 may cause ischaemia for Asian patients with LM stenosis.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of consensus: 93.8% agree; 3.1% neutral; 3.1% disagree.

Statement 3. An MLA of >6 mm2 should be considered as a threshold for deferral of revascularisation for Asian patients.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of consensus: 87.5% agree; 9.4% neutral; 3.1% disagree.

Statement 4. Fractional flow reserve (FFR) should be considered in patients with LM stenosis with MLA 4.5 to 6.0 mm2 to guide decisionmaking.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of consensus: 90.6% agree; 3.1% neutral; 6.3% disagree.

Statement 5. Intravascular imaging should be considered when performing LM PCI.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of consensus: 96.9% agree; 0% neutral; 3.1% disagree.

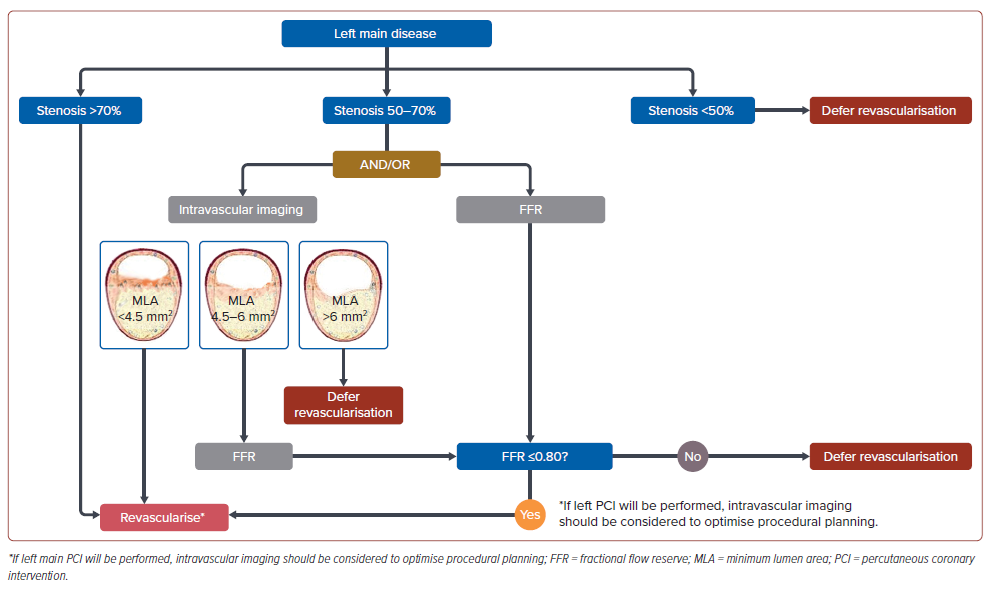

Coronary angiography remains the preferred imaging modality for the evaluation of LM stenosis. However, this modality has limitations, such as high inter-reader variability, especially in intermediate lesions.6–8 Hence, other imaging modalities are recommended to further guide the decision to revascularise LM stenosis. These include intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or optical coherence tomography as well as invasive functional techniques such as FFR.9 Such modalities are recommended to inform clinicians of the severity of the LM stenosis and the decision for revascularisation or deferral. Intravenous adenosine during FFR testing should be considered in the setting of LM disease, especially in ostial LM disease.10

The MLA derived from IVUS is important anatomical information to describe the ischaemic burden of an LM stenosis. Evidence derived from a Korean population found that an MLA ≤4.5 mm2 is associated with a functionally significant LMCA stenosis. Based on this study, this consensus uses MLA ≤4.5 mm2 as a threshold to revascularise. Conversely, an MLA >6 mm2 is generally accepted as the safe and optimal threshold for deferring revascularisation of LM stenosis.

Physiological assessment may also be used to decide between deferral or revascularisation of LM stenosis. Physiological assessment by FFR has been reported to be able to identify visual-functional mismatch in approximately 30–40% of intermediate LM stenosis.11,12 Intermediate lesions with FFR >0.80 could be safely deferred.11,13 A few studies found that an iFR >0.89 is a useful cut-off for deferral of revascularisation of LM stenosis; however, iFR has been associated with excess deaths, and is not recommended.14–17 Given that physiological testing is more readily available in the Asian-Pacific region, this modality should be considered in patients with intermediate LM stenosis or those with an MLA of 4.5–6 mm2 .

Intravascular imaging should be considered when performing LM PCI.18,19 For example, intracoronary imaging is a valuable tool for the assessment and procedural optimisation of patients with LM stenosis planned for intervention. IVUS may be used to assess plaque distribution, which is important for informing the best stenting strategy.

A suggested algorithm for the imaging and revascularisation deferral of patients with LM stenosis is shown in Figure 1.

Finally, the decision on the imaging strategy should be made after careful consideration of the availability and accessibility of the various imaging modalities and the incremental information these modalities may provide to the individual patient’s treatment plan.

Indications for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Versus Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting in Selected Patients

Statement 6. Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is recommended for patients with diabetes and multivessel disease involving the LMCA. PCI may be considered in patients who refuse or are ineligible for surgery.

Level of evidence: High.

Level of consensus: 93.8% agree; 0% neutral; 6.3% disagree.

Statement 7. The treatment of LM stenosis in patients with severe chronic kidney disease (CKD) should be individualised.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of consensus: 100% agree; 0% neutral; 0% disagree.

Statement 8. CABG should be considered in patients with LM stenosis and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF; <40%). However, PCI may be considered for those who refuse or are ineligible for surgery.

Level of evidence: Moderate.

Level of consensus: 90.6% agree; 6.3% neutral; 3.1% disagree.

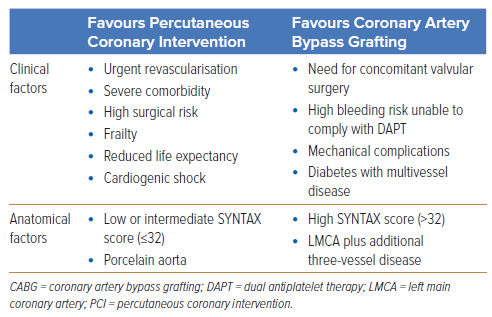

CABG is generally considered the most appropriate treatment for LM stenosis. However, there is growing evidence indicating that PCI can be an alternative to CABG in certain patient subgroups.20 A meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials comparing CABG and PCI showed no significant difference in all-cause death, cardiac mortality, stroke or MI. However, unplanned revascularisation was less frequent after CABG.21 A meta-analysis of individual patient data also found no statistically significant difference in 5-year all-cause death between PCI and CABG. However, spontaneous MI and repeat revascularisation were more common with PCI. In contrast, stroke risk was lower with PCI in the first year.

The European Society of Cardiology suggests PCI as an alternative to CABG in LM stenosis patients with low SYNTAX score (<23).22 Similarly, the American Heart Association gave a class IIa recommendation for PCI in patients with a low risk of procedural complications, a high likelihood of favourable long-term outcomes and clinical features indicating an increased risk of adverse surgical outcomes.23

Overall, PCI of LM stenosis requires an experienced operator and the consideration of multiple anatomical and clinical factors. These factors are summarised in Table 1. It should be emphasised that CABG and PCI are in equipoise in many real-world clinical scenarios. Hence, the decision on the revascularisation strategy should be made through a heart team approach after careful consideration of all important anatomical and clinical factors together with the patient’s preferences.

Additionally, several patient subgroups require special consideration; these include those with diabetes, severe CKD or those with reduced ejection fraction (ejection fraction <40%).

Patients with diabetes are more likely to have complex coronary artery disease, such as multivessel disease or LM stenosis.18 Furthermore, these patients generally have a greater atherosclerotic burden and have poorer outcomes compared with those without diabetes.24

Several subgroup analyses of trials comparing patients with LM stenosis or multivessel disease treated with PCI or CABG found that, in patients with diabetes, PCI was associated with increased revascularisation rates while CABG was associated with a higher risk of stroke.25–30

Given the low likelihood of a low SYNTAX score and the increased atherosclerotic burden in patients with diabetes and LM stenosis, CABG is usually considered the standard of care.31 However, PCI is a reasonable option for patients who refuse or are ineligible for surgery.

For patients with CKD, the risks of both CABG and PCI should be considered. When treated with CABG, patients with CKD face poor prognosis because of the risk of acute renal failure and other comorbidities.32–34 However, PCI is associated with acute renal failure from contrast media and atheroemboli.35,36

The EXCEL trial compared the effectiveness of PCI versus CABG in patients with LM stenosis with low or intermediate anatomical complexity and a sub-analysis according to baseline renal function was performed. The study found that acute renal failure occurred less frequently after PCI compared with CABG while the rate of the primary composite endpoint of death, MI or stroke at 3-year follow-up were similar.37

In contrast, a patient-pooled analysis of patients treated with PCI found a higher risk of target lesion failure in patients with severe CKD and dialysisdependent patients compared with those without CKD.38 Given the inherently high risk of patients with severe CKD, treatment of LM stenosis patients with severe CKD should be individualised.

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction is a common long-term complication of LM stenosis due to the large area of at-risk myocardium.39,40 The IRIS-MAIN registry showed that, in patients with LM stenosis and moderately or severely reduced LVEF, CABG was associated with a lower risk of the composite outcome of death, MI or stroke compared with PCI.41 Hence, CABG should be considered in patients with moderately or severely reduced LVEF, especially if complete revascularisation cannot be achieved with PCI, given that the surgical risk is acceptable. It should be noted that the IRIS-MAIN study found that the incremental benefit of CABG over PCI diminishes if PCI achieves complete revascularisation.41

Stenting Strategy

Statement 9. . In patients with LM stenosis planned for PCI, complete revascularisation should be considered whenever possible.

Level of evidence: High.

Level of consensus: 93.8% agree; 6.2% neutral; 0% disagree.

Statement 10. Stepwise provisional stenting should be considered for patients with non-complex LM stenosis.

Level of evidence: High.

Level of consensus: 96.9% agree; 3.1% neutral; 0% disagree.

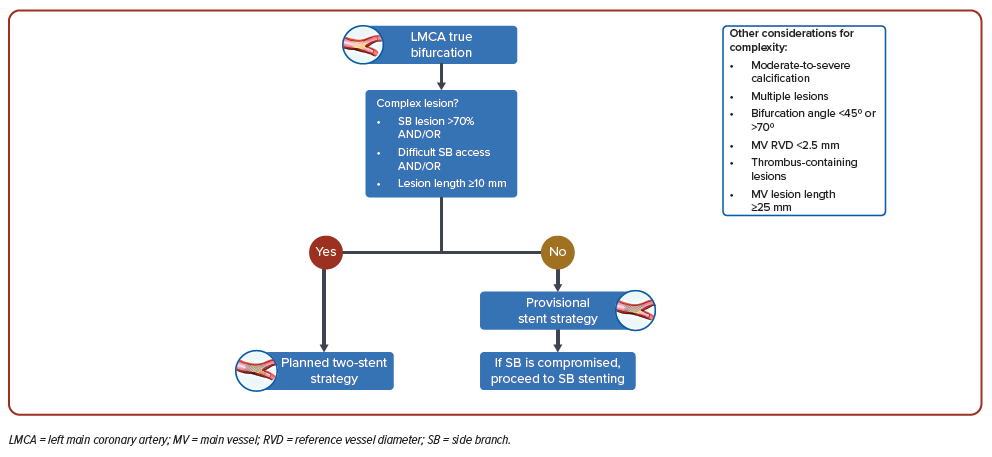

Statement 11. Planned two-stent approach should be considered for complex LM bifurcation stenosis (side branch lesion >70% and/or difficult side branch access and/or lesion length ≥10 mm).

Level of evidence: High.

Level of consensus: 87.4% agree; 6.3% neutral; 6.3% disagree.

LM stenosis is often associated with lesions in other areas of the coronary circulation. Evidence indicates that complete revascularisation should be attempted as much as possible because incomplete revascularisation is associated with poorer patient outcomes, regardless of the revascularisation strategy.18,42 Furthermore, for most patients, surgery and PCI achieve similar rates of the composite outcome of death, MI and stroke at the 5-year follow-up.43 Accomplishing complete revascularisation requires assessment of the extent and complexity of the coronary artery disease and careful planning by the heart team.

Approximately 70% of patients with LM stenosis have non-complex lesions and would benefit from a one-stent strategy.44,45 In these patients, a stepwise provisional stent strategy aiming to initially cover with a single stent from the most relevant and diseased vessel back into the main stem is appropriate and reassessed for the need for subsequent stenting.46,47 The EBC MAIN study (n=467) found that, in patients with true LM bifurcation lesions, a stepwise provisional stent strategy was associated with a trend towards a lower risk of the composite endpoint of death, MI or target lesion revascularisation at 12 months (p=0.34).48

In contrast, a planned two-stent approach should be considered for patients with complex LM bifurcation stenosis. The DEFINITION II trial (n=653) found that in patients with complex LM bifurcation lesions, patients treated with a planned two-stent approach experienced fewer target lesion failures at 1 year compared with those treated with a stepwise provisional approach (HR 0.52; 95% CI [0.30–0.90]; p=0.019).49 The risk of target vessel MI (HR 0.43; 95% CI [0.20–0.90]; p=0.025) and clinically driven target lesion revascularisation (HR 0.43; 95% CI [0.19– 1.00]; p=0.049) was also lower in the planned two-stent-approach group.

A suggested algorithm for the stenting strategy of patients with LM stenosis being considered for PCI is shown in Figure 2.

Dual Antiplatelet Therapy

Statement 12. For patients with chronic coronary syndrome LM stenosis, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for 6–12 months post-PCI should be considered. However, DAPT duration should be individualised to balance the patient’s individual ischaemic and bleeding risk.

Level of evidence: Low.

Level of consensus: 93.8% agree, 3.1% neutral, 3.1% disagree.

PCI in the treatment of LM stenosis may be a complex procedure, which increases the risk of stent thrombosis. Hence, DAPT must be initiated to prevent this complication. International guidelines recommend a longer duration of DAPT in patients who undergo complex PCI because of the high risk of ischaemic events.9,50,51 The multicentre Euro Bifurcation Club – P2BiTO – registry found a DAPT duration of <6 months to be associated with a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) compared with a DAPT duration of 6 to 12 months (14% versus 10%, respectively; p<0.001). A longer DAPT duration (>12 months) did not reduce the risk of MACE any further.52 However, a longer DAPT duration may be associated with an increased risk of bleeding. Therefore, DAPT duration should be individualised to balance the patient’s individual ischaemic and bleeding risk. Factors that favour a shorter DAPT duration include old age (>75 years), severe CKD and other comorbidities and medications that increase bleeding risk, the use of a single stent, the use of IVUS, main vessel reference diameter >3 mm and the use of drugeluting stents.

Limitations and Conclusion

The 12 statements presented in this paper aim to guide clinicians based on the most up-to-date evidence and collective expert opinion from Asia-Pacific. However, given the varied clinical situations and healthcare resources present in the region, these recommendations should augment clinical judgement rather than replace it. The use of PCI in the management of LM stenosis should be individualised, considering the patient’s clinical characteristics as well as patient and caregiver concerns and preferences. Clinicians should also be aware of the challenges that may limit the applicability of these consensus recommendations in their centre, such as access to specific interventions and technologies, availability of resources including the competency level of clinical staff, accepted local standards of care and cultural factors. Nonetheless, these consensus statements may help create and improve protocols and pathways for the use of PCI in the management of LM stenosis in centres across the Asia-Pacific region to best benefit patients.

Clinical Perspective

- Intravascular imaging or physiological testing is recommended to assess left main coronary artery stenosis (LM stenosis) with intermediate diameter stenosis.

- The decision on the revascularisation strategy (percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting) should be made through a heart team approach after careful consideration of multiple anatomical and clinical factors together with the patient’s preferences.

- In patients with LM stenosis planned for percutaneous coronary intervention, complete revascularisation should be considered whenever possible. Stepwise provisional stenting should be considered for patients with non-complex LM stenosis, but a planned two-stent approach should be considered for complex LM bifurcation stenosis.

- Clinicians should also be aware of the challenges that may limit the applicability of these consensus recommendations in the management of LM stenosis in their centres.