The prognoses of heart failure with mildly reduced (HFmrEF) and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) have significantly improved with increasing uptake of contemporary heart failure therapies. This has placed growing importance on the management of other potential life- limiting non-cardiac comorbidities among patients with HFmrEF and HFrEF. In addition to cardiovascular disease, cancer remains a leading cause of mortality globally despite improvements in prevention, screening and treatment.1 Preclinical and epidemiological studies have suggested that patients with heart failure are at increased risk of future incident cancer.2–4 However, routine cancer screening is not commonly discussed during cardiovascular healthcare provision or endorsed by current cardiovascular guidelines. This study sought to describe the uptake and perception of cancer screening among patients with HFmrEF and HFrEF.

Methods

We performed a prospective survey of 200 consecutive ambulatory patients attending a specialised heart failure clinic at a tertiary hospital in Australia from 2022–2023. Patients were included if they were eligible for recommended breast, cervical and/or bowel cancer screening according to Australian guidelines, had HFmrEF or HFrEF (i.e. an ejection fraction of <50%) and no prior history of cancer.

In Australia, three national cancer screening programmes are available on a voluntary basis free of cost: breast cancer screening every 2 years for females aged 50–74 years, cervical cancer screening every 5 years for females aged 25–74 years and bowel cancer screening every 2 years for individuals aged 50–74 years.

Institutional ethics approval was obtained and written informed consent was obtained prior to survey completion. Medical history, socioeconomic factors (geographic remoteness, employment, annual income, education level), participation in cancer screening and perceptions towards cancer screening were recorded.

Perception towards cancer screening was assessed using questions about the awareness of the associations between heart failure and cancer, appropriateness of cancer screening discussions during heart failure healthcare visits, perceptions towards routine cancer screening for patients with heart failure and interest in participating in cancer screening programmes.

The primary endpoint was adherence to recommended cancer screening, defined as up-to-date participation in all cancer screening according to Australian guidelines. Comparisons were made using Χ2 analysis or Wilcoxon rank-sum test between participants who were adherent to cancer screening against those who were not to identify predictors for adherence.

Cancer screening participation rates were also compared with those of the general Australian population as reported by Australian national cancer screening programmes.5

Results

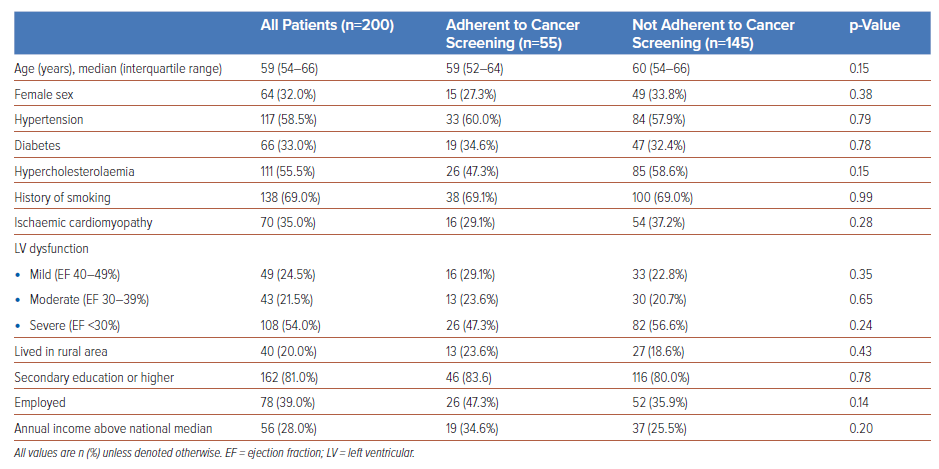

A total of 243 consecutive patients who were eligible for cancer screening in Australia were reviewed to obtain the target population. Of these, 40 patients were excluded due to a prior history of cancer and three declined consent. Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. The median age was 59 years (interquartile range: 54–66 years) and 64 (32%) were female. A total of 117 participants (58.5%) had hypertension, 66 (33%) diabetes, 111 (55.5%) hypercholesterolaemia and 138 (69%) a history of smoking. Seventy participants (35%) had ischaemic cardiomyopathy and 108 (54%) had severe left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction <30%) at time of diagnosis. Forty participants (20%) lived in a rural area and 162 (81%) completed secondary education or higher. Seventy-eight participants (39%) were employed and 56 (28%) had an annual income above the national median. Within the cohort, 44 participants (22%) were eligible for breast cancer screening, 63 (31.5%) for cervical cancer screening and 181 (90.5%) for bowel cancer screening.

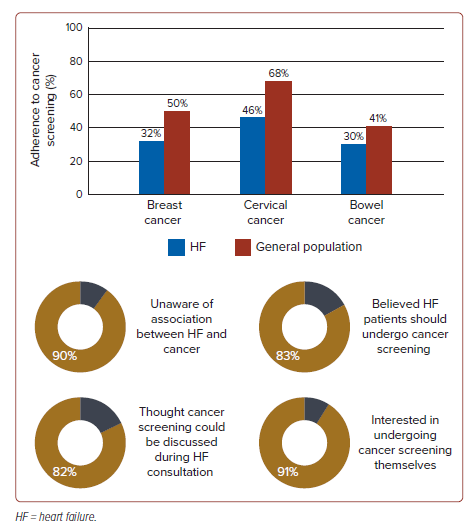

There were 55 participants (28%) adherent to cancer screening. When analysed individually, 14 participants (32%) were adherent to breast cancer screening, 29 (46%) to cervical cancer screening and 55 (30%) to bowel cancer screening. There were no significant differences in medical history and socioeconomic factors between those who were and were not adherent to cancer screening (Table 1). Rates of cancer screening were lower in the study population compared with the general Australian population for all three cancer types: 32% versus 50% for breast cancer, 46% versus 68% for cervical cancer and 30% versus 41% for bowel cancer (Figure 1).5

Within the cohort, 179 participants (90%) were unaware of the associations between heart failure and cancer. There were 163 participants (82%) who thought discussions about cancer screening were appropriate during cardiovascular consultation. A total of 166 participants (83%) believed all patients with heart failure should undergo routine cancer screening and 181 (91%) were interested in undergoing cancer screening themselves.

Discussion

In this study of 200 patients with HFmrEF and HFrEF, we found a low uptake of recommended breast, cervical and bowel cancer screening among patients, despite the availability of free national cancer screening programmes in Australia. Established chronic disease has been associated with reduced uptake of cancer screening, presumably because of low perceived utility in the setting of competing comorbidity risk.6

This study has replicated similar results within a heart failure cohort and suggests that poor uptake of cancer screening may not be because of a lack of interest among patients, but lack of awareness of the importance of cancer screening among patients and/or healthcare providers. Heart failure patients often have regular long-term follow-up, creating an opportunity for patients to be educated about cancer screening within existing models of care, which could involve primary care providers and nurse practitioners.

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations, including the small patient population and single-centre setting. Only participants who attended clinic follow-up were reviewed, thus potentially introducing selection bias towards a more adherent population. Because of Australian recommendations, participation in screening for other cancers that may be recommended in other countries, such as prostate and lung cancer, was not assessed. The survey used was limited in assessing other factors that could limit voluntary participation in cancer screening, such as quality of life, frailty, mental health and other significant comorbidities. Finally, the survey did not include interventions to promote cancer screening among patients and thus could not assess change in behaviour over time.

Conclusion

There was reduced uptake of breast, cervical and bowel cancer screening among patients with HFmrEF and HFrEF. There was interest for participation in cancer screening among patients and further efforts could be targeted at improving patient and cardiovascular healthcare provider education on cancer screening.

Clinical Perspective

- Patients with heart failure have low adherence to recommended cancer screening.

- This is because of a lack of awareness on the importance of cancer screening.

- There is interest for cancer screening participation among heart failure patients.

- Education on cancer screening among patients with heart failure should be improved.