Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been the leading cause of death in Asia even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, causing 10.8 million deaths annually and accounting for more than half of all CVD deaths worldwide.1,2

In addition to its direct effect on excess mortality, the COVID-19 pandemic has also caused an increase in the number of CVD deaths in Asia. There were interruptions in essential CVD care pathways in primary prevention, diagnostic imaging, acute care, invasive procedures, cardiac rehabilitation and chronic care during the pandemic.3–10

Although there have been a number of reports on how the pandemic has affected the number of CVD-related outpatient visits and hospital admissions, its impact on early to mid-career cardiovascular surgeons’ and physicians’ daily lives and practice have not been well characterised, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic there were reports on physician burnout, largely caused by the overwhelming workload or COVID-19 care, particularly in the critical care setting.11,12 Although critical care intensivists, pulmonologists, infectious disease specialists and general medical physicians played a central role in treating COVID-19 patients, many cardiovascular physicians also contributed to mitigate the impact of the pandemic, often at the cost of their required cardiovascular training, research and even personal time spent with family.13,14 The impact varies at different stages of career, but may be particularly significant for the younger early to mid-career physicians whose careers are in the process of developing.

The aim of this study was to understand the experiences and perspectives of early to mid-career physicians and surgeons involved in cardiovascular care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Asia-Pacific, a region with diverse culture, language and history.

Methods

Established in April 1956, the Asian Pacific Society of Cardiology (APSC) currently represents 23 cardiology societies in the Asia-Pacific region. The APSC young community is a subset of the APSC, and seeks to promote educational and research initiatives among the younger cardiology community in the region. (Supplementary Table 1). Members are generally 45 years old or younger and are early to mid-career cardiologists or cardiothoracic surgeons.15

Study Design and Participants

This study was a cross-sectional survey that was conducted using Google Forms, a web-based survey system. Response collection began on 19 June 2023 and was closed on 2 July 2023, 2 weeks after initiation. A total of 135 members of the APSC young community were sent the questionnaire via email, and a dedicated social group messaging platform was created for the members who had chosen to participate. The questionnaire required approximately 7–8 minutes to complete. Data extraction was performed on 4 July and data cleaning was completed on 10 July 2023. This study received an exemption from review by the Japanese Circulation Society, Institutional Review Board.

Survey Questions

The survey was designed to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2023, as compared with the year 2019 (as the final pre-pandemic year as reference). The survey consisted of the following four subsections: demographic characteristics of respondents; changes in volume of CVD patients; changes in clinical practice and research; and local demand and interest in long-COVID research. Details of the survey are given in Supplementary Table 2.

Statistical Analysis

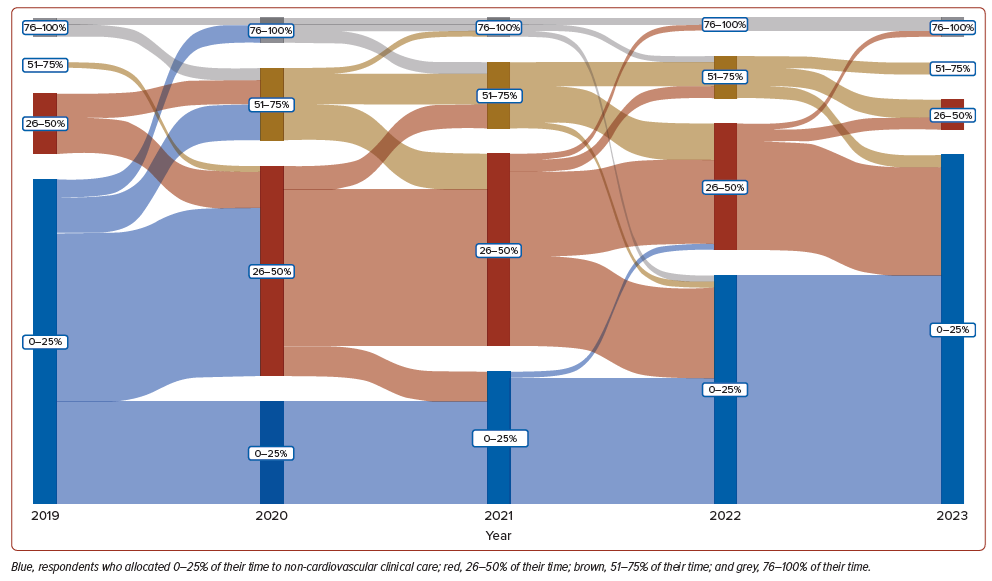

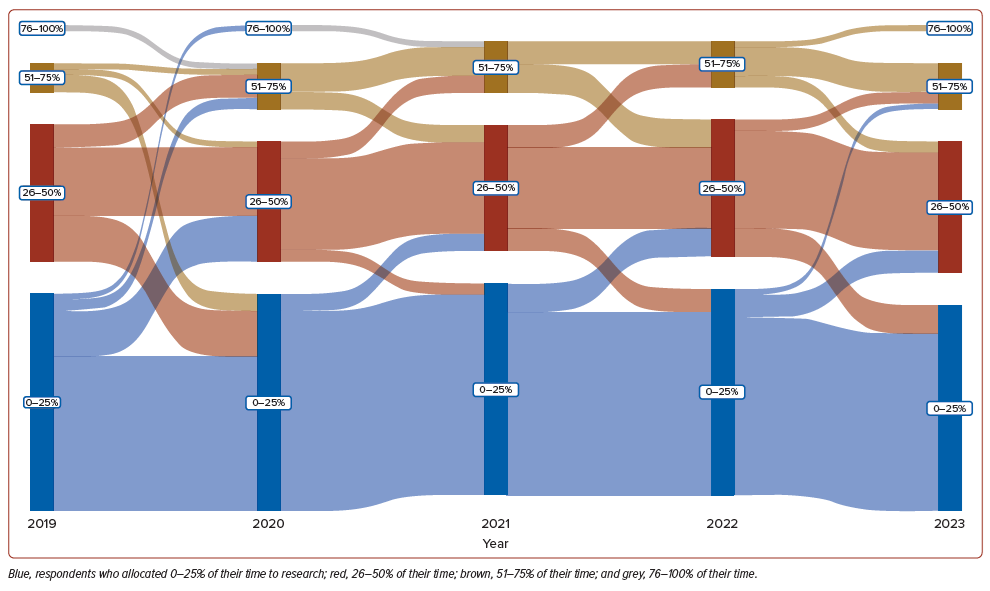

We divided Asian countries into four regions (Eastern, Southeastern, Southern, and Central and Western) according to the United Nations’ geographical regions.16 Distribution and proportions of each characteristic by region are given as mean ± SD, or as percentages. The Sankey diagram, a flow diagram wherein the width corresponds proportionately to the flow rate, was used to illustrate the sequence changes in percentage of time spent on non-cardiovascular care and research prior to, and throughout, the pandemic years. The diagram was plotted using the R package ggsankey. All analyses were performed using R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

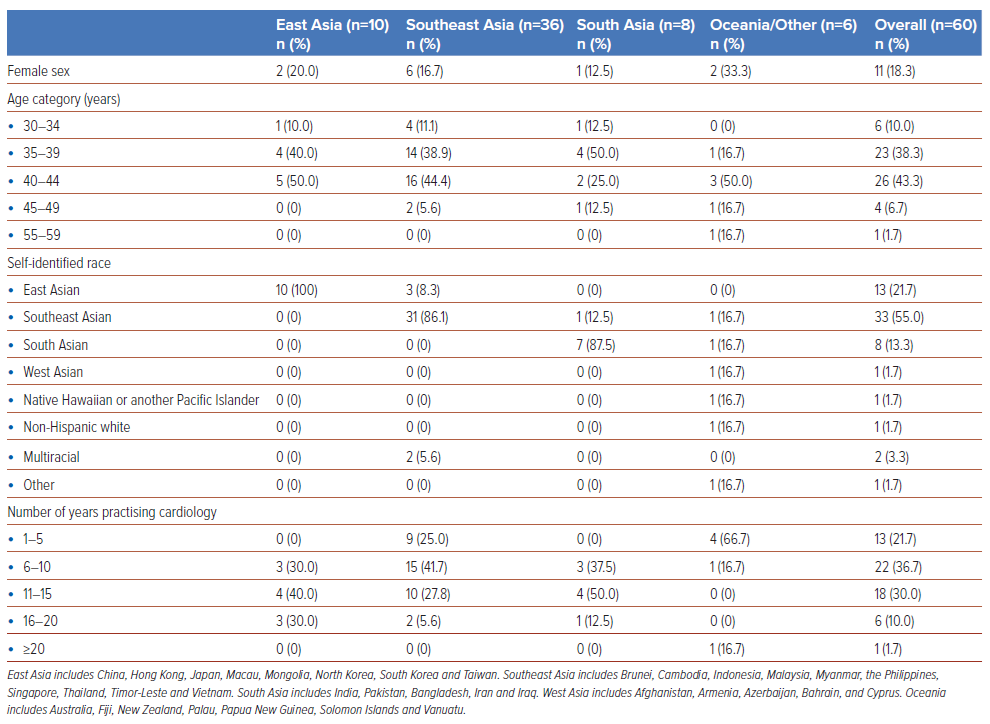

Overall, 60 members (44%) practicing in 23 countries in the Asian Pacific region responded to the survey. The majority of respondents were male (81.7%), and more than half of the respondents self-identified as Southeast Asian (55.0%), followed by East Asian (21.7%) and South Asian (13.3%; Table 1). The age group of 40–44 years was the most represented (43.3%), followed by those aged 35–39 years (38.3%) and 30–34 years (10.0%). The top clinical areas that respondents were involved in were general cardiology (76.5%), interventional cardiology (57.4%), critical care (26.5%), cardiac imaging (26.5%) and advanced heart failure or transplantation (26.5%). Respondents had varying experience in cardiovascular care practice, with the majority (36.7%) having 6–10 years of experience in the practice of cardiology.

Trends in Cardiovascular Care during the Pandemic

In 2020, 70.0% of respondents reported a reduction in patient volume (Supplementary Table 3). However, in 2021 and 2022 an increase in patient volumes was reported by 26.7% and 51.7% of respondents, respectively. By 2023, 60.0% of respondents indicated a rise in overall patient volume. With regard to acute MI (AMI) patients, 65.0% of respondents saw a decrease in 2020; in 2021, 46.7% were still experiencing a decrease. By 2022, 30.0% saw an increase in the number of AMI patients, and 41.7% reported an increase in AMI patients by 2023. In 2020, 80.0% of respondents reported a significant decrease in the number of elective cardiac procedures. Although procedure numbers remained low in 2021 and 2022 (70.0% and 23.3% respectively), by 2023 41.7% observed an increase. Acute heart failure (AHF) case trends varied, with 58.3% of respondents noting a decline in 2020. Subsequent years had fluctuating decreases and no changes.

Trends in Non-cardiovascular Care and Research during the Pandemic

When participants were asked “On a typical week, how has the percentage of time spent on non-cardiovascular care (e.g. care for COVID patients without CV complications) changed before and after the pandemic started?” in 2019, the majority of respondents (80.0%) reported that they dedicated less than a quarter of their work hours to non-cardiovascular care (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 4). However, this shifted in 2020 and 2021, with a larger proportion (48.3% and 40.0%, respectively) devoting 26–50% of their work hours to non-cardiovascular care. By 2022 and 2023, the majority had reverted to dedicating 0–25% of their clinical hours to non-cardiovascular care (60.0% and 90.0%, respectively).

In terms of research, in 2019, 60.0% of respondents allocated 0–25% of their time, 35.0% allocated 26–50%, and 1.7% allocated 76–100% of their time to research (Figure 2). Similar patterns were noted in 2020 and 2021, with the majority (56.7% and 58.3%, respectively) dedicating 0–25% of their time to research. In 2022 the distribution was 55.0% for 0–25%, 33.3% for 26–50%, and 11.7% for 51–75%. By 2023 the breakdown was 58.3% for 0–25% research time and 31.7% for 26–50% research time.

Clinical Care, Research and Personal Life during the Pandemic

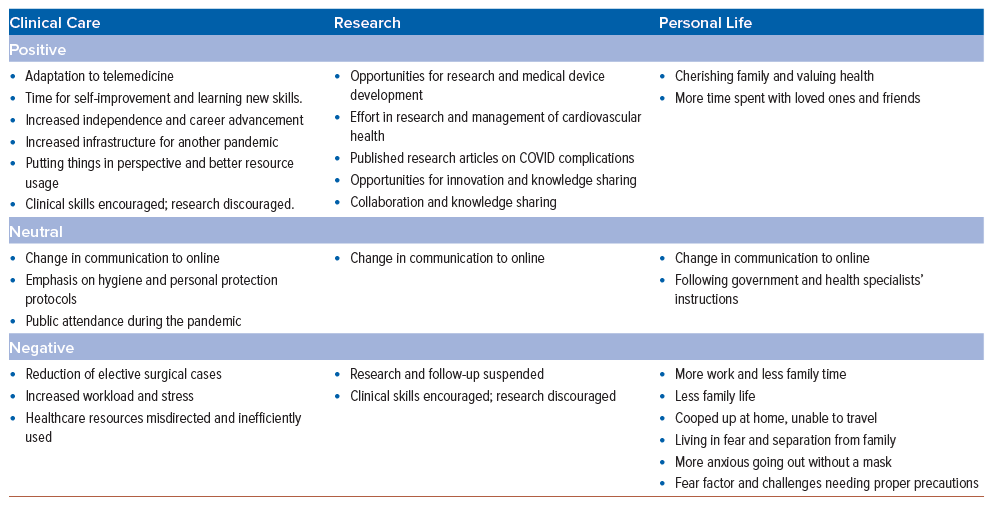

The majority of the respondents reported significant changes in clinical care, research and personal life during the pandemic (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 5). On a positive note, respondents reported that the healthcare sector has shown remarkable adaptability, with the adoption of telemedicine and the implementation of better resource management. Researchers have seized opportunities to develop medical devices, and some have succeeded in publishing articles on COVID-related complications, fostering collaboration and knowledge sharing. Many have embraced the value of family and health, cherishing quality time with loved ones while dedicating time to self-improvement and skill-building. On the negative side, some of the respondents reported facing increased workloads, reduced family time, higher stress, and limitations on research time, affecting progress. Moreover, the fear factor and challenges of living through the pandemic caused anxiety and feelings of being cooped up at home.

Public Interest, Research Funding and Respondent Interest in Long COVID

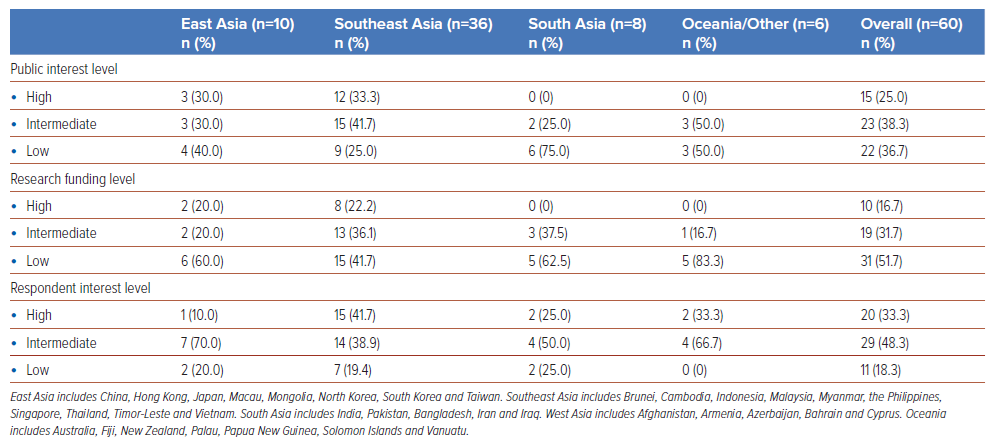

Public interest in long COVID was considered high by 25.0% of respondents, moderate by 38.3% and low by 36.7% (Table 3). In terms of research funding availability for long COVID, 16.7% of respondents reported high levels of funding, 31.7% reported moderate funding, and 51.7% reported low funding. Respondents from South Asia (63%) and Oceania or other regions (83%) reported low funding for long-COVID research. With respect to the respondent’s personal interest in understanding long COVID, 33.3% of respondents expressed high interest, 48.3% showed moderate interest, and 18.3% indicated low interest. Notably, respondent personal interest in understanding long COVID was highest in the Southeast Asia region, with high public interest and funding available.

Discussion

This survey study, conducted 1 month after the WHO lifted the state of public health emergency, explored the experiences of early to mid-career physicians and surgeons engaged in cardiovascular care in a multistate Asia-Pacific healthcare provider community.17 The research identified distinctive aspects and insights, shedding light on the unique challenges and opportunities faced by these healthcare professionals during the critical period from the early stages of the pandemic to its mid-term impact. Some individuals managed to find silver linings, while others struggled to shift their clinical work to non-cardiovascular care. This led to overwhelming workloads, reduced family time, higher stress, and limited research opportunities, hindering professional growth. As we move forward into the post-COVID era, a prominent challenge emerges: meeting the requirements of patients struggling with long COVID. This concern is particularly pronounced in the Southeast Asia region, reflecting both a strong individual interest among respondents and a substantial level of public attention and dedicated funding aimed at tackling this issue.

Our findings add to the existing literature in three ways. First, the experiences of early and mid-career physicians and surgeons in the Asia-Pacific region were captured across the entirety of the COVID-19 pandemic, extending beyond the earlier phase of the pandemic. During the initial stages of the pandemic, several reports highlighted the impact of the pandemic on the volumes of coronary intervention procedures and how it disrupted training opportunities for early-career professionals.5–9,13,14 Our study captured similar respondent-perceived trends throughout the Asia-Pacific region, and also identified that the majority of physicians and surgeons who specialised in cardiovascular care were heavily involved in care outside of their specialty during this time of crisis. Further assessment is required to understand the mid- to long-term consequences of the disruption in cardiovascular training, which could potentially jeopardise quality of care, given that procedure volume serves as a benchmark for hospital-based quality care delivery.18,19

Second, respondents indicated a substantial reduction in the number of cardiovascular patients arriving at hospital in 2020. This was followed by a gradual return to baseline levels, but the projection for 2023 suggests a concerning surge in cardiovascular patients, possibly indicating a push-back effect that could strain capacity, especially in areas with restricted access to primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention.20 While certain East Asian countries foresee a decline in cardiovascular deaths, other regions might face contrary trends due to ongoing increases, driven by the escalating prevalence of obesity as a rapidly growing metabolic risk factor.21–23 Additionally, projections for CVD-related hospitalisations remain unexamined and necessitate validation through conventional databases. Addressing the potential delayed indirect impact of the pandemic could involve enhancing outreach to high-risk individuals residing in the region.

Last, the respondents exhibited a reasonable degree of interest in long-COVID research, most noted among cardiovascular specialists from Southeast Asia. Long COVID, defined as ongoing, relapsing or new symptoms or conditions that are present 30 or more days after infection, is a major clinical and public health concern.24 While cases of acute COVID infection were traditionally categorised as requiring predominantly non-cardiovascular medical attention, long COVID presents via a more comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach.25 Chest pain, palpitations, exercise intolerance and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome are some of the most commonly observed cardiovascular symptoms associated with long COVID. It is worth noting that the level of awareness about this condition, both among the public and in the medical community, can vary significantly across different regions. Nonetheless, at least 65 million individuals globally are projected to be affected by long COVID, and with cases on the rise daily, an escalation in patients reporting these symptoms is expected. In Pakistan, 83.7% of patients reported residual symptoms even 1 month after COVID-19 infection, while in India, the figure was 29% for individuals affected by acute COVID, and in Bangladesh the prevalence of long-COVID symptoms at 12 weeks was 16.1%.26–29 This underscores the need for enhanced recognition, understanding and management of long COVID as it continues to affect an increasing number of individuals.

Limitations

There are several limitations to consider. First, the sample size is too small to conclusively determine the impact of COVID-19 on cardiovascular practice in the Asia-Pacific region. However, this multinational survey could provide valuable insights for future, larger-scale research in this field. Second, given that this is a retrospective questionnaire survey, recall bias cannot be disregarded. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that the APSC young community members may not fully represent the experience of all of the senior and junior cardiologists in the Asia-Pacific region. This could introduce a selection bias, potentially tilting towards individuals who are particularly driven and engaged in both clinical and research endeavours. As a result, the perspectives shared might predominantly reflect the more exceptional experiences rather than capturing the broader sentiment in the entire professional community.

Conclusion

Our post-pandemic survey highlighted challenges faced by early to mid-career cardiovascular physicians in the Asian Pacific network, including adapting to non-cardiovascular care while contending with reduced cardiovascular training opportunities, heavier workloads, time constraints, stress and limited research options. In the future, the pandemic’s aftermath might lead to an influx of cardiovascular patients, straining capacity in regions with limited preventive access. Physicians at this stage of their career face unique challenges that should be considered and addressed when timing and resources are appropriate. As future emergencies loom, adaptable and resilient systems will be crucial to uphold cardiovascular care standards in the Asia-Pacific region. Finally, addressing long COVID’s cardiovascular effects could evolve into a major public concern.

Our study identified challenges faced by early and mid-career cardiovascular physicians in the Asia-Pacific region, adapting to non-cardiovascular care while managing heavy workloads and constrained training opportunities. This study emphasises the significance of establishing adaptable systems to maintain cardiovascular care standards and address evolving requirements such as long COVID, particularly in anticipation of future emergencies in the Asia-Pacific region.

Clinical Perspective

- This survey study conducted 1 month after the WHO lifted the COVID-19 state of public health emergency highlights difficulties experienced by early to mid-career cardiovascular physicians in the Asia-Pacific region.

- Challenges included adapting to non-cardiovascular care, reduced cardiovascular training opportunities, heavier workloads, time constraints, stress, and limited research options.

- Addressing the cardiovascular effects of long COVID could become a significant public concern.