Approximately 25% of patients hospitalised for acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) are at risk of future re-hospitalisation or mortality within 1 month of discharge.1 Rates of mortality and hospitalisation are equally poor in Malaysia, with 30-day mortality and rehospitalisation reaching levels as high as 13.1–15.7% and 4.1–11.2%, respectively, based on local data.2,3 Over the past decade, there has remained a large emphasis on the optimisation of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) during the ‘vulnerable phase’ following decompensation, with a focus on in-hospital initiation of GDMT to overcome prescription inertia among clinicians.4,5 Unfortunately, pressures on hospital systems restrict the duration of inpatient stay, which often lasts between 5 and 9 days and is often insufficient to concurrently manage acute congestion while attempting to uptitrate GDMT doses.2,3,6

Of the various strategies proposed over the past decade, multidisciplinary team heart failure (MDT-HF) clinics have been shown to be beneficial in increasing key GDMT prescriptions, with strong recommendations made by both the European Society of Cardiology (class 1a) and American College of Cardiology (class 1b), especially in vulnerable patients.7,8 The aim of this study was to report on our experience running an early, post-discharge MDT-HF clinic – the first of its kind in Malaysia.

Methods

Study Centre

A retrospective review was conducted at our institution – Institut Jantung Negara (IJN), Malaysia. IJN is a major cardiac tertiary centre in Kuala Lumpur, and is also the major referral centre for advanced heart failure (HF) care, including heart transplantation, and left ventricular assist device and complex cardiovascular implantable electronic device (CIED) implantation. There is also an active inpatient and outpatient HF service providing multidisciplinary care involving cardiologists, cardiothoracic surgeons, pharmacists, nurse specialists, physiotherapists and cardiac rehabilitation specialists.

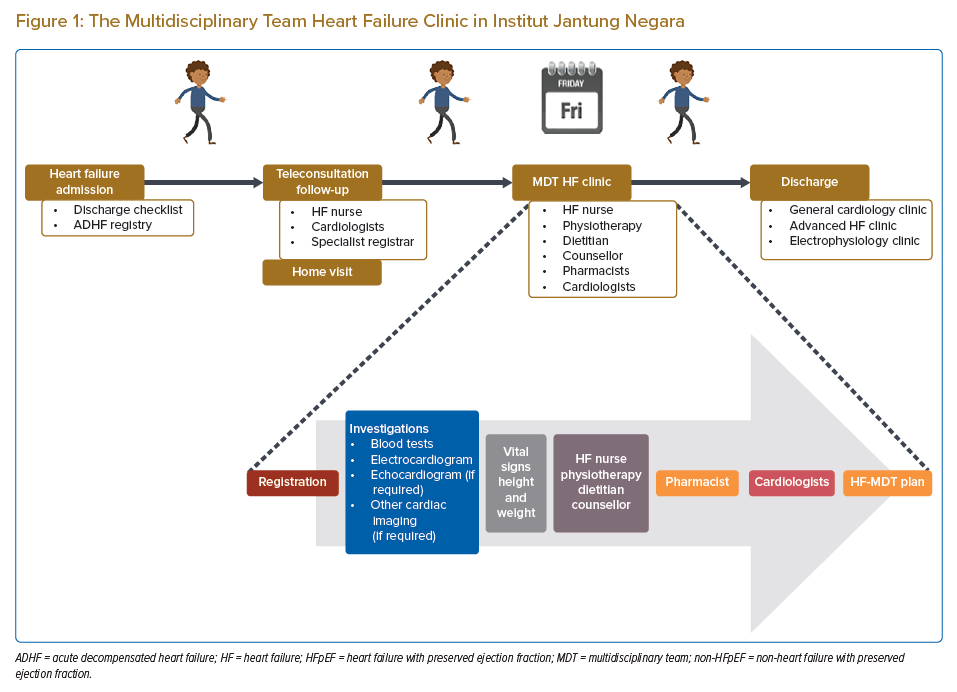

At the institution, all acute admissions for HF are entered into a local database as part of an ADHF registry (Figure 1). Patients admitted for ADHF are also given a discharge checklist to ensure that necessary medications and counselling are provided prior to discharge. Patients are also concurrently screened by our team of nurse specialists and ward nurses for eligibility for follow-up under our teleconsultation or MDT-HF clinic services. The MDT-HF clinic was first initiated in July 2019 and continues to be an ongoing service provided to all clinicians at IJN via formal inpatient referral to the HF team (Figure 1). The HF team consists of two consultant HF cardiologists and one or two specialist registrars. The clinic reviews up to 10 patients per session, together with a team consisting of doctors, HF pharmacists, HF nurses, a physiotherapist, dietitian and counsellor. Patients seen in the MDT-HF clinic include those recently admitted for ADHF and are often seen in the 7–12 days after discharge.

The main objectives in the MDT-HF clinic primarily revolve around improving GDMT optimisation and functional status (i.e. physical and mental wellbeing), symptom monitoring, and monitoring for adverse effects related to pharmacotherapy. During the initial stages of designing the MDT-HF clinic, patients were required to have an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) >30 ml/min/1.73 m2 and have good social support to be eligible for referral, to ensure that they would benefit from the clinic and to limit barriers to successful uptitration of GDMT. However, over time, this requirement was enforced less and less, and the clinic has since included consultations with patients who have end-stage renal failure and those on renal replacement therapy. Given that medication prescription at our institution is fully funded by the institution, good social support was essential in our setting to ensure adherence to GDMT because it is often costly. However, the eGFR level used remains arbitrary with no objective measure per se, and, given that all patients initially seen in our clinic were never excluded, we have since omitted this from our requirement as of June 2022.

Following optimisation of GDMT, patients are subsequently discharged from the MDT-HF clinic (after an average duration of 6–12 weeks of follow-up) to one of the following: a general cardiology clinic for routine care; an advanced HF clinic for consideration of advanced HF therapy (i.e. ventricular assist device implantation or heart transplantation); or an electrophysiology clinic for consideration of CIED, if eligible for either.

Study Design and Study Population

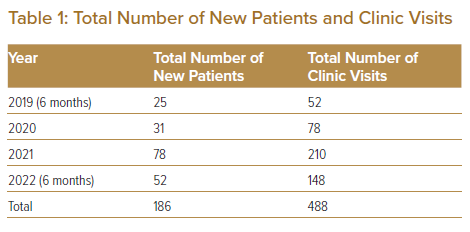

Data from ambulatory patients reviewed in the MDT-HF clinic between 1 July 2019 and 31 June 2022 were obtained through the IJN MDT-HF registry. Selection was through universal sampling. A total of 186 patients and 488 clinic encounters were identified.

Information gathered included baseline demographics, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), comorbidities, clinical variables (systolic and diastolic blood pressure [SBP and DBP], heart rate [HR], symptoms and signs), blood investigations and clinical outcomes. Data on groups of medication prescribed, the pattern of prescription (initiation, increment and decrement of medication doses) and number of GDMTs prescribed were also analysed. Furthermore, information on counselling provided to the patients by both pharmacists and HF nurses was also obtained. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise baseline demographic, comorbidities, vital signs, blood investigation and clinical outcomes. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables are summarised as the mean and SD, or median and IQR.

The IJN Research Ethics Committee (IJNREC) reviewed and approved this study. The committee is constituted and operates according to the Malaysian Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH)–GCP guidelines. The study conforms to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, GCP and the laws and regulations of Malaysia, in which the research is conducted.

Results

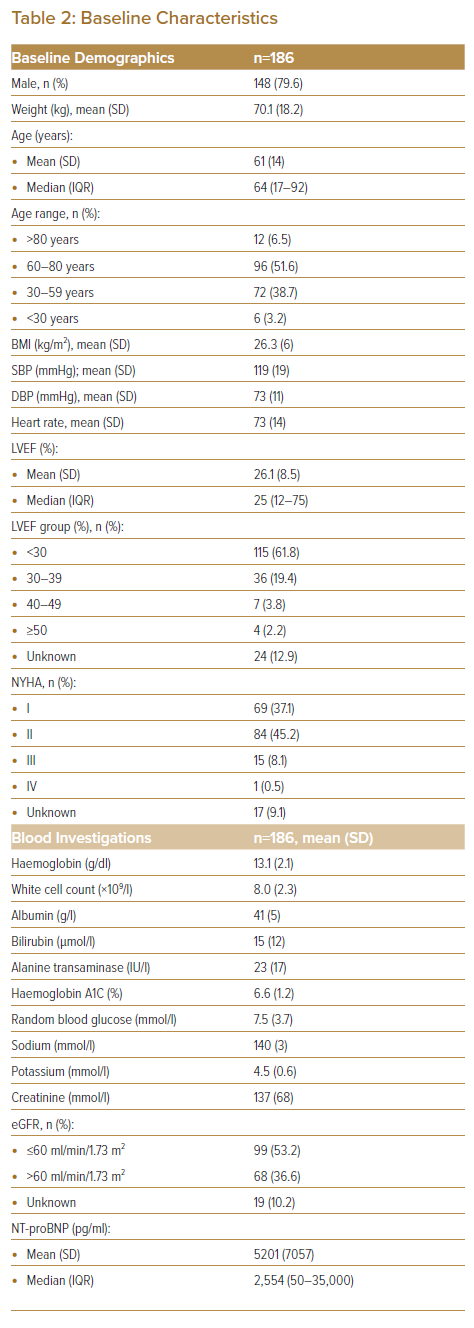

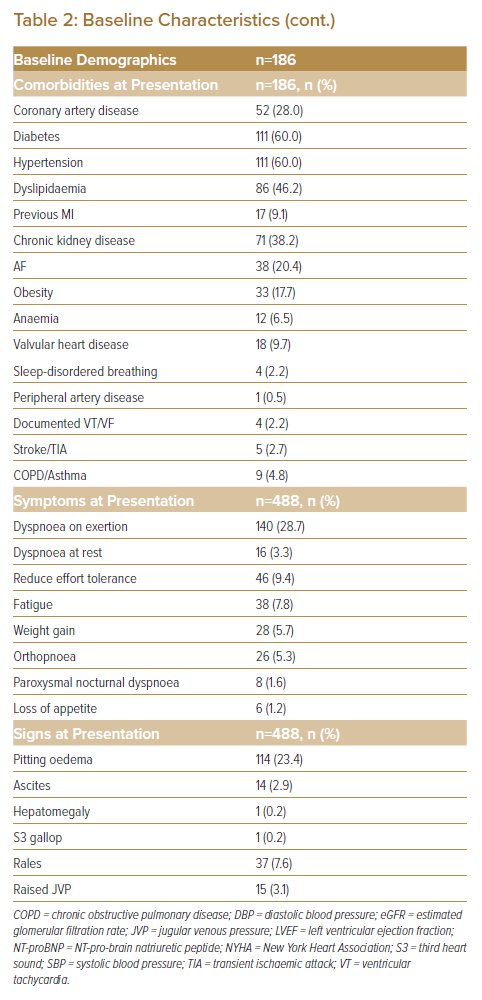

In total, 186 patients were reviewed in the MDT-HF clinic between 1 July 2019 and 30 June 2022, with a total of 488 clinic encounters (Table 1). Of these, 148 patients (79.6%) were male (Table 2). The mean and median age of patients attending the clinic were 61 ± 14 years and 64 years, respectively, the majority (51.6%) of whom were in the 60–80-year age range. Patients were mainly of NYHA functional class II (45.2%), which usually warrants uptitration of medication as per guidelines, thus the need for referral to such services. The mean weight and BMI were 70.1 ± 18.2 kg and 26.3 ± 6 kg/m2. Blood pressure and HR were stable at the time of first clinic review (SBP, DBP and HR 119 ± 19 mmHg, 73 ± 11 mmHg and 73 ± 14 BPM, respectively; Table 2). The mean LVEF was 26.1 ± 8.5%, with the majority of patients having LVEF <30% (61.8%). Although we did not restrict patients with unknown LVEF from being reviewed in the MDT-HF clinic, of the 24 patients with no known LVEF during their initial clinic consultation, all had undergone some form of bedside echocardiography that established the presence of dilated cardiomyopathy with an estimated ejection fraction below 40%.

Blood investigations during each visit, on average, were relatively stable aside from creatinine (137 ± 68 mmol/l), eGFR (53.2% of patients with levels ≤60 ml/min/1.73 m2) and NT-pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP; mean and median of 5,201 ± 7,057 pg/ml and 2,554 pg/ml, respectively; Table 2). Common comorbidities included diabetes (60.0%), hypertension (60.0%), dyslipidaemia (46.2%) and chronic kidney disease (38.2%). The commonest symptoms reported in the clinic were dyspnoea on exertion (28.7%) and reduced effort tolerance (9.4%), and the commonest sign was pitting oedema (23.4%).

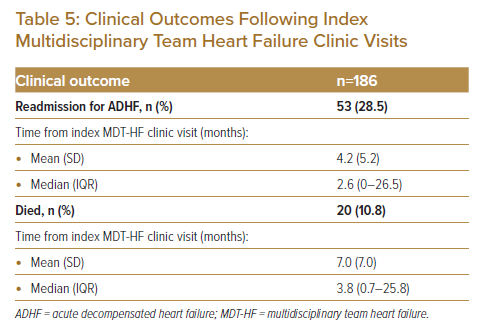

Of the medications prescribed at last clinic review (Table 3), with regard to HF, a substantial proportion of patients were prescribed angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI) (85.5%), β-blockers (83.9%), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) (86.0%) and diuretics (88.2%). There was also a high degree of statin (88.2%) and aspirin (61.8%) prescription. When analysing prescription patterns during each clinic visit, a high proportion of new prescriptions and further uptitration were for ARNI (9.8% and 40.0%, respectively), β-blockers (7.6% and 18.6%, respectively), and MRA (8.2% and 11.9%, respectively). The majority of downtitrations were for diuretics (20.7%), followed by ARNI (5.7%). Of the 28 encounters that had required downtitration of ARNI, 20 of these cases were due to symptomatic hypotension, while the remaining eight were due to worsening renal function beyond the recommended allowance for creatinine rise (with or without hyperkalaemia). A large proportion of patients were on either three or four GDMTs by their last clinic review (37.6% and 49.5%, respectively; Table 3).

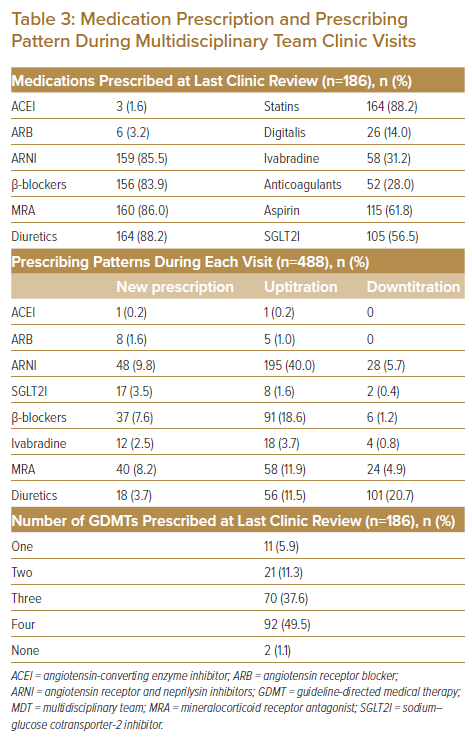

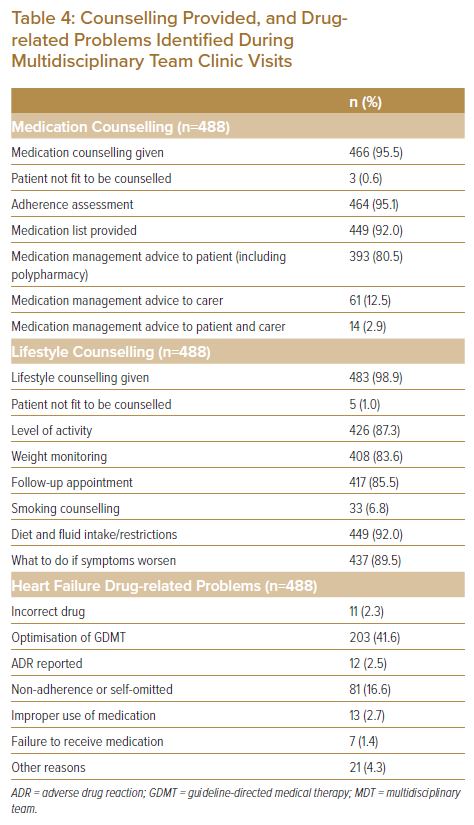

Although a large proportion of counselling provided during the MDT-HF clinics centres around appropriate medication use, management of polypharmacy and other medication-related issues (i.e. adherence, self-cessation), a reasonable amount of time is spent on other non-pharmacotherapy-related areas, such as diet and fluid restriction (92.0%), levels of activity permitted (87.3%), weight monitoring (8.36%) and steps to undertake in the event of worsening symptoms (89.5%; Table 4). Common problem areas related to medication identified included difficulty in optimisation of GDMT (41.6%) and non-adherence or self-omission (16.6%) of medication prescription. Of the 186 patients, 28.5% had readmission at some point during the study period, which occurred in the 4.2 ± 5.2 months after their index MDT-HF clinic visit on average (Table 5). None of the patients, however, had any readmission events in the 30 days after their index admission. Furthermore, 10.8% of patients died in the 7.0 ± 7.0 months after their initial visit (Table 5). Of the 20 deaths that occurred, 16 of those were due to worsening ADHF events and four were due to ventricular arrhythmia.

Discussion

Many factors have been linked to poor uptitration of GDMT in HF patients. These can be largely divided into three main problem areas: healthcare systems factors (e.g. restrictive policies and pricing in using pharmacological therapies, inadequate information technology advances or poor access to speciality and/or multidisciplinary care); clinician factors (e.g. prescribing inertia or gaps in knowledge regarding efficacy, safety or tolerability of new agents); and patient factors (e.g. financial constraints, poor health literacy, fear surrounding changes in management or healthcare services in general).9 Early, post-discharge MDT clinics aim to bridge the gap between multispecialty accessible care and optimum HF care, which is particular pertinent to avoid decompensation of clinical state that often occurs during the vulnerable phase of the disease trajectory.4

The younger, male-predominant population seen in our MDT-HF clinic is unsurprising and reflects previously reported data on ADHF in Malaysia.2,3,6 The majority of patients had HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), which again is unsurprising given that it is this group that would most benefit from initiation and uptitration of GDMT.10–12 Furthermore, the majority of ADHF patients in Malaysia consist of patients with HFrEF, which is often ischaemic in aetiology.2,3,6,13,14 The high rates of cardiometabolic risk factors (i.e. hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia and chronic kidney disease) in our patients also mimic that of these registries and studies, and further support this observation.2,3,6

The deranged renal function in our cohort is a testament to the issue often faced by clinicians in the inpatient setting: acute renal impairment that causes prescription inertia of key pharmacotherapy, despite it being proven repeatedly that rising creatinine following GDMT is not detrimental (and in fact is expected in the majority of cases as an indicator of optimisation).15–18 This further highlights the importance of early follow-up and close monitoring in this group of patients to avoid missing opportunities for treatment uptitration. This is further supported by the raised NT-proBNP levels on clinic presentation, which illustrates the high degree of vulnerability in this cohort.4,11,19

Prescribing patterns observed in our MDT-HF clinics parallel the goals of running such a clinic: a strong focus on initiation and further uptitration of the ‘four pillars of heart failure’.10–12 The majority of patients were on either ARNI, β-blockers or MRA. Fewer patients were on sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2Is), possibly because the evidence for SGLT2I use in HF patients was still in development during the initial period of establishment of the MDT-HF clinic.11 Of note, aspirin and statin use was also high in our MDT-HF patients, again due to higher rates of ischaemic cardiomyopathy. It was reassuring to observe how a large proportion of patients attending the MDT-HF clinic were on either three or four GDMT (87.1% combined; Table 3).

The counselling provided during our MDT-HF clinic aims at providing holistic care to HF patients.7,8,20 Alongside education on self-care and medication management, there is an emphasis on providing structured physical and psychological support following hospitalisation, given that this may be traumatic for many. In fact, rates of mood disorders are among the highest with regards to the associated comorbidities in HF, with 20% of HF patients experiencing depression, half of whom have severe depression.11 Frailty, sarcopenia and cachexia also provide unique challenges in HF patients, underlining the need for a multidisciplinary approach incorporating physiotherapy, nutrition and rehabilitation services.11 Lifestyle counselling and consultation enable gaps in care to be identified, which then lead to referrals to a physiotherapist, occupational therapist or counsellors when indicated. The establishment of a structured service, such as an MDT-HF clinic, enables these adjunct services to be more accessible to patients. Unfortunately, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire score was not incorporated into the design of the initial MDT-HF clinic, which would have assisted in highlighting gaps in the care of HF patients, specifically pertaining to psychosocial domains.21,22 As of June 2022, efforts are being made to improve on the design of the clinic, and incorporation of the score is being carefully considered.

There is still much debate with regard to streamlining the terms of the models of care and services provided, focusing largely on whether it is best delivered in a community versus a hospital setting; and whether remote monitoring and management can be incorporated into such comprehensive care, especially given the recent COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on healthcare systems worldwide.7–9,23–26 Nevertheless, adoption of an MDT approach has been shown to be cost-effective; it has improved adherence to medical treatment, reduced the length of inpatient stay, and can lead to lower hospital readmissions and mortality.

Limitations

This analysis is limited by a small sample population with no validation analysis performed to compare experiences with other MDT efforts worldwide. However, to our knowledge, our MDT-HF clinic experience was unique in its set-up and there have not been any other reports published locally or regionally. Therefore, the analysis provided remains valuable for future research and development. Furthermore, unfortunately, data on HF patients seen in the ambulatory setting in our centre prior to the establishment of the MDT-HF clinic are not readily accessible for comparison. We thus decided to keep the manuscript descriptive, at best, to share our local experience in piloting an MDT-HF clinic. It would be beneficial, however, to compare the data presented in our paper with those of other clinical settings (i.e. primary care management, general cardiology clinics or other dedicated HF clinic initiatives) to understand the true extent of benefit from running an MDT-HF clinic before expansion of such services regionally, especially in key endpoints, such as mortality and readmissions.

Conclusion

Although definitions may differ between healthcare systems, MDT-based services undeniably offer evidence-based, holistic care to patients, regardless of the disease or condition being managed. This is especially important in complex, chronic conditions such as HF. Hopefully, our description of the establishment of the first MDT-HF clinic targeted at transitional care will encourage the development of similar services across the region, and subsequently improve outcomes in HF patients, which remain poor in our region.

Clinical Perspective

- Optimisation of guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) during the ‘vulnerable phase’ of heart failure is key.

- Multidisciplinary team heart failure clinics have been shown to be beneficial in increasing key GDMT prescriptions.

- Furthermore, adopting a multidisciplinary team approach has been shown to be cost-effective, has improved adherence to medical treatment, reduced length of inpatient stay, and can lead to lower hospital readmissions and mortality.