The Eustachian valve (EV) is a congenital remnant arising from the fossa of the inferior vena cava (IVC).1,2 Rarely, it can appear as an elongated structure and allow for the appearance of various right atrial masses or structures.3,4 This case report describes a unique case of a misinterpreted EV mimicking an inter-atrial septal (IAS) defect.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with acute onset of dyspnoea, epigastric pain and vomiting. The patient was known to have hypertension but was otherwise well before admission. Clinical examination revealed a respiratory rate of 30 breaths/minute, oxygen saturations of 88% at room temperature requiring oxygen supplementation, and a temperature of 36.4°C. However, there was no evidence of central or peripheral cyanosis. Her jugular venous pressure was raised, measuring 4 cm vertically from the sternal angle. There was diffuse rhonchi on auscultation, with reduced breath sounds on both bases of her lungs. There was also a grade 3 diastolic murmur detected on auscultation of the patient’s precordium, with a loud second heart sound and gallop rhythm appreciated. A chest X-ray showed evidence of acute pulmonary oedema, which the patient subsequently received treatment for using IV furosemide.

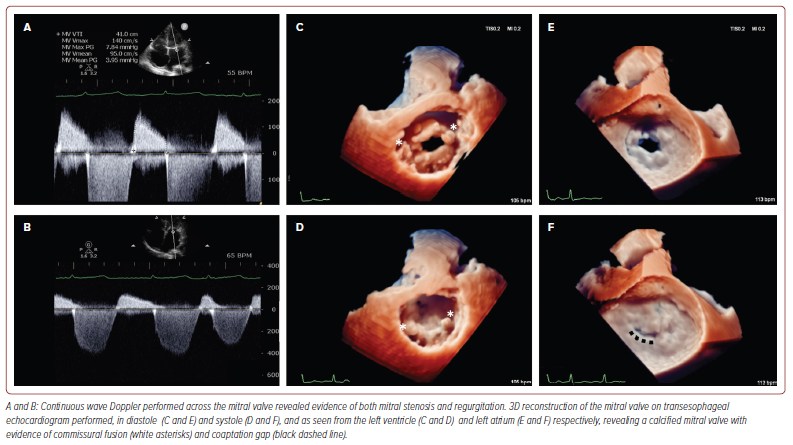

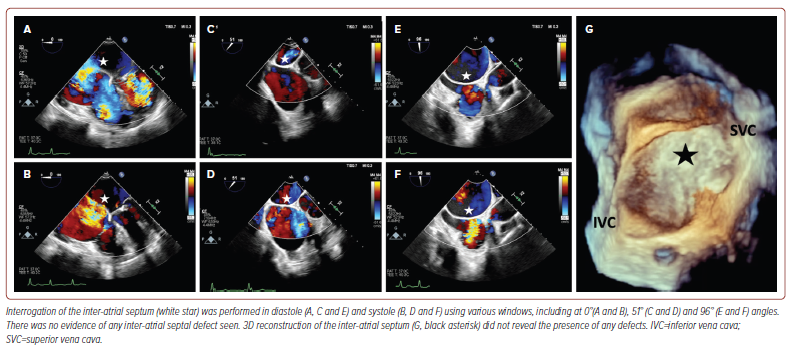

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed a reduced left ventricular (LV) systolic function (LV ejection fraction 35%) with normal wall thickness. The right ventricle had normal dimensions and function and there was biatrial dilatation with a left atrial volume index of 54 ml/m2 and a right atrial volume index of 42 ml/m2. In addition, TTE revealed evidence of moderate mitral stenosis, with a mitral valve mean gradient measuring 3.95 mmHg with a pressure half-time of 190 ms and mitral valve orifice area of 1.2 cm2 on planimetry. There was also moderate mitral regurgitation (vena contracta width (VCW) 0.5 cm and an effective regurgitation orifice area of 0.35 cm2, but with blunting of pulmonary vein systolic flow) and severe, functional tricuspid regurgitation (tricuspid valve annulus diameter 4.2 cm, VCW 0.8 cm, hepatic vein systolic flow reversal and dense triangular jet on continuous wave Doppler). Overall, the likely aetiology for the mitral valve pathology was felt to be rheumatic in nature. Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) was then performed, with 3D reconstruction to corroborate the findings of TTE (Figure 1). In addition to thoroughly evaluating the valves, the IAS was interrogated on TOE revealing an absence of any defects (Figure 2 and Supplementary Video 1).

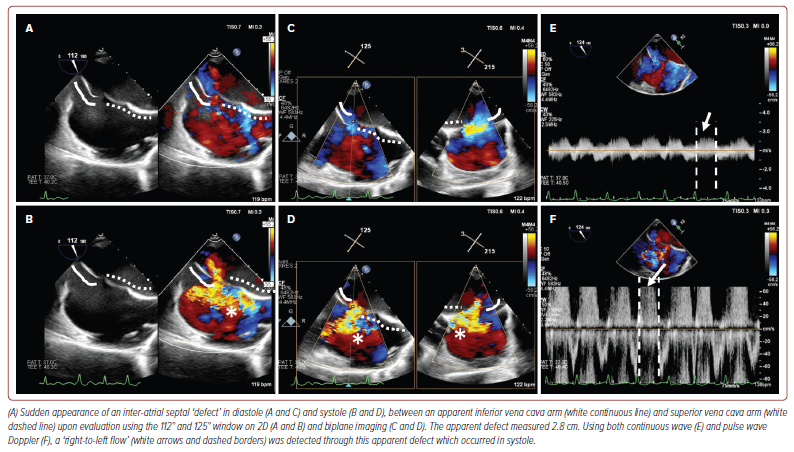

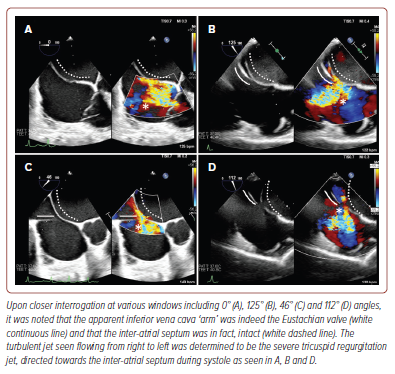

Surprisingly, upon TOE evaluation using the 112° and 125° windows, an interatrial ‘defect’ measuring 2.8 cm had suddenly appeared, with turbulent flow seen through this ‘defect’ on colour-flow Doppler (CFD; Figure 3 and Supplementary Video 2). The turbulent jet originated from within the right atrium and moved towards the IAS, and was also apparent on both continuous wave and pulse wave Doppler imaging. This was peculiar as we were expecting higher left atrial pressures seeing the predominantly rightward shift of the IAS. However, on closer interrogation using various windows, it became clear that one of the ‘arms’ of the apparent IAS defect was instead an elongated structure arising from the borders of the IVC, measuring between 2.0 to 2.5 cm in length suggestive of an EV (Figure 4 and Supplementary Video 3). Employing CFD alongside multiplanar imaging, it was shown that the turbulent jet was in fact the severe tricuspid regurgitation and that there was indeed continuation of the IAS with no breakthrough of the jet surpassing the IAS boundaries. The case was subsequently discussed in a multidisciplinary meeting with consensus that there was no inter-atrial defect and that management via percutaneous mitral commissurotomy could be pursued.

Discussion

Persistent EV often occurs following incomplete regression of the sinus venosus during birth.3 When present, it commonly appears as a crescentic fold of endocardium arising from the anterior rim of the IVC.1,2

Rarely, persistence of this vestige may manifest in various ways including that of a mobile, elongated appendage protruding within the right atrium.2,3 It may cross the floor of the atrium from the IVC and insert into the lower portion of the IAS adjacent to the atrioventricular valves or have a higher insertion which allows it to mimic a divided right atrium, mimicking a cor triatriatum.1,3,4 In any event, an EV measuring above 10 mm is usually considered to be large.5

Often persistent EV are incidentally discovered via TTE and most patients with persistent EV remain well and require no treatment.2 However, large EV may coexist with an atrial septal defect or patent foramen ovale and have been reported to increase right-to-left shunting leading to cyanosis during early infancy and requiring surgical intervention. Large EV may also produce IVC flow obstruction and potentially lead to challenging advancement of procedural catheters and wires across the IVC – an important consideration, considering the rising popularity of transcatheter-based interventions.2,6,7 Other potential, albeit rare, complications include endocarditis and thrombus formation over the valve in at-risk individuals, for example, IV drug users and those with coexisting congenital heart defects.3,8

Our case highlights another potential issue in the presence of a large EV. Occasionally, a large EV can be mistaken for other structures including cor triatriatum dexter, right cystic masses or a vegetation arising from the tricuspid valve, which often may warrant other modalities of cardiac imaging to help uncover the true diagnosis of the EV.1,3,6

Rarely, a large EV may be misdiagnosed as an arm of an IAS defect as demonstrated in our case and reported in a handful of other cases.4,9 There have been reports of misinterpretation leading to inappropriate surgical or percutaneous closure of the interatrial septum and EV, which have led to restricted inflow into the right atrium.4 Although the haemodynamic consequence of such closure remains unknown and possibly benign, nevertheless it is still pertinent to ensure that such misinterpretation is avoided to circumvent any unnecessary interventions.

As seen in our case, misinterpretation of an apparent IAS defect had occurred due to several factors, including the presence of a severe, functional tricuspid regurgitation jet directed towards the interatrial septum alongside the presence of significant biatrial dilatation which commonly exist with IAS defects. However, we quickly realised the discordant finding of a lack of clinical cyanosis and rightward shift of the IAS (suggestive of raised left atrial pressure), despite the apparent ‘right-to-left shunt’, which led us to perform additional interrogation.

Conclusion

Benign masses in the right atrium, including EV, are commonly reported from echocardiography. Giant, elongated EV are rare but important structures to identify during routine TTE and TOE. Misinterpretation of giant EV for other intracardiac structures can be systematically avoided if there is a clear understanding of the right atrial anatomy and physiology.

Clinical Perspective

- Eustachian valves are an embryological remnant that can persist into adulthood, although this is not common.

- Rarely, Eustachian valves can be large enough to deceptively mimic interatrial septal defects.

- Good understanding of atrial anatomy and right atrial flow is needed to avoid misinterpretation.