Heart failure (HF) is a common condition associated with high mortality, recurrent hospitalisations and a poor quality of life. Its prevalence is increasing worldwide due to population ageing and suboptimal control of risk factors, such as diabetes and arterial hypertension.1–3

The therapeutic management of HF has dramatically changed over the past 40 years. In the 1970s, only diuretic agents and digitalis were available to treat patients with HF. Since then, a number of large controlled clinical trials have demonstrated the benefits of several classes of medication to improve the prognosis, hospitalisation rate and the quality of life of people with HF: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis); β-blockers; angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs); mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs); If channel blockers; angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNis); and, more recently, sodium–glucose cotransporter inhibitors (SGLT2is).1–3

These have been tested successfully in people with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), in whom they significantly reduce cardiovascular mortality and HF hospitalisations. All these have a class I recommendation except If channel inhibitor ivabradine, which has a class IIa recommendation. Some of these classes of drugs are also beneficial in HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Two SGLT2is – dapagliflozin and empagliflozin – reduce morbidity and mortality and have a class I recommendation. Spironolactone (an MRA) and ARNis have also showed a reduction in hospitalisation in some subgroups; ARNis seem to be more efficient in women than in men.1–3

The use of these drugs has resulted in a dramatic reduction in risks of cardiovascular death and HF hospitalisations as demonstrated by network analyses; international guidelines recognise the benefits of these drugs and, in particular, the latest guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommend their broad use with a class I recommendation.1–3

Despite these advancements in HF treatment, a number of observational studies have shown that the implementation of guidelines in clinical practice remains suboptimal worldwide and that patients with HF do not receive recommended medications. Moreover, when they are prescribed, underdosage remains a major issue.

The purpose of this article is to review the current situation, analyse the reasons why HF guidelines implementation remains suboptimal and examine the consequences on clinical outcomes.

Prescription Rates and Dosages: A Suboptimal Situation

The ESC HF Long-term Registry, which included more than 12,000 patients from 21 ESC countries between 2011 and 2013, showed that the rate of prescription of major HF medications has been fairly satisfactory in both patients in hospital and outpatients. ACEis/ARBs, β-blockers and MRAs were prescribed in 77%, 72% and 54% of patients at discharge after a hospitalisation for HF and in 89%, 89% and 59% in outpatients, respectively.4 The rate of prescription was higher in outpatients with HFrEF than with HFpEF.5 Only a minority of patients were at target dose as recommended by the ESC guidelines – 29% for ACEis, 24% for ARBs and 17% for β-blockers.

In the CHECK-HF survey, which pooled 5,701 patients with HFrEF from 34 Dutch hospitals, the rate of prescription of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors (RASis) and β-blockers was also high (>80%), but the analysis of individual hospitals showed considerable heterogeneity from one centre to another.6 Most concerning was that 24% of patients treated with an ACEi or an ARB and 45% of patients treated with a β-blocker received <50% of the target recommended dose. These results are in line with data from the QUALIFY registry, which enrolled 7,092 outpatients with HFrEF from 36 countries and found that 52% of the patients treated with β-blockers received at least 50% of the target recommended dose and 15% were at target dose.7

The ASIAN-HF registry enrolled 5,276 patients with HFrEF and an episode of decompensation in the previous 6 months at 46 centres in 11 Asian countries. The rate of prescription of ACEis/ARBs, β-blockers and MRAs was, overall, generally satisfactory (77%, 79% and 58%, respectively), but the investigators noticed substantial regional variations and widespread underdosing: guideline-recommended target dosing was observed in 17% of cases for ACEis/ARBs, 13% for β-blockers and 29% for MRAs.8

More recently, a survey was conducted among 489 hospitals in the US, which enrolled 49,399 patients.9 The rate of prescription of SGLT2is was assessed and, again, considerable heterogeneity was observed between centres. Moreover, only 19 out of 489 hospitals prescribed this drug at discharge in >50% of cases, although this class of drug does not require titration and has few side-effects. It has been suggested that a lack of SGLT2i prescription at discharge was associated with a poor rate of prescription of other recommended medications including β-blockers, ARNis and MRAs at 30 days and 1 year, which suggests it is a reflection of poor adherence to guidelines at large.10

Longer-term surveys have suggested that little changes with time after discharge from the hospital. Analysis of new users of HF medications derived from healthcare databases in the US, the UK and Sweden have shown that, at 12 months, target dosages were achieved in a minority of patients (15% ACEi; 10% ARB; 12% β-blocker; and 30% sacubitril/valsartan) and rates of discontinuation were concerning (55% ACEi; 33% ARB; 24% β-blockers; 27% sacubitril/valsartan; and 40% MRA).11

A similar observation came from the PINNACLE registry in the US, which enrolled 11,064 patients with HFrEF and worsening HF.12 On average, dosages of ACEis/ARBs and of β-blockers remained unchanged 6 months after the worsening event and the majority of patients were treated with <50% of the target recommended dosage, suggesting therapeutic inertia after discharge. This lack of change in dosage was also observed in the international QUALIFY registry, which showed that, after 18 months of follow-up, changes in dosage of ACEis, ARBs, β-blockers, ivabradine and MRAs remained uncommon.13

Factors of Poor Guideline Adoption

Patient Factors

A number of factors inherent to a patient can limit the use or titration of recommended medications. Side-effects, contraindications and comorbidities, such as lung disease, kidney dysfunction or frailty, are among the most common ones.

In the CHECK registry, older age was associated with a lower rate of prescription of recommended medications as well as a reduced likelihood of uptitration.6 In QUALIFY, the target dose of ACEis at baseline was less likely to be achieved in patients with chronic kidney disease and age was a limiting factor for β-blockers.7 At the 18-month follow-up, age, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic kidney disease were independent predictors of non-uptitration of β-blockers.7

Other factors, such as depression, cognitive disorders or cancer, may also limit adoption of guidelines.

Age is often associated with poor adherence to treatment although, in the absence of side-effects or contraindications, observational studies have suggested that guideline-recommended therapies are beneficial. The Swedish heart failure registry showed that the prescription of RASis was beneficial regarding overall mortality and a composite endpoint in octogenarians.14

Sex plays a role, and surveys have suggested that women tend to be less often treated by recommended medications than men.15 A number of factors, including the impact of societal traditions, lower economic status and older age may explain this inequality.

Side-effects are a limiting factor in the adoption of guidelines. The most common ones are hypotension, fatigue (β-blockers) and bradycardia (β-blockers) or renal dysfunction (MRAs and RASis). To limit the incidence of these side-effects, a check of co-prescription of drugs that may induce hypotension or bradycardia or impair renal function, but are not otherwise necessary for the management of HF, should be carried out in a systematic fashion.

Polypharmacy is routine in the management of HF and is another limiting factor, particularly in elderly patients with cognitive disorders where family members or care professionals may need to be involved to prevent mistakes. Moreover, some patients are reluctant to take many pills every day and the role of each medication needs to be clearly explained.

Finally, patient education and awareness of the goals of HF treatment and of the warning signs and symptoms of imminent decompensation is important because this condition is associated with acute decompensation.

Economic and Organisational Factors

The cost of medications and, more broadly, the lack of healthcare resources are limitations to adherence to guidelines, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

The REPORT-HF study, which covered 44 countries, included 8,969 patients with HFrEF hospitalised for acute HF. It showed that the proportion of patients treated by RASis, β-blockers and MRAs is lower in low- and middle-income countries and in people without health insurance.15 Similarly, the transition from hospital to outpatient facilities is often poorly organised, leading to medical inertia and a lack of titration when needed.

Physician Factors

Variations in knowledge and practice may play a role in guideline adoption. GPs are often less aware of the objectives of treatment and, compared to cardiologists, tend to focus more on immediate symptom relief than on longer-term key outcomes, such as survival or hospitalisations. A lack of time or resources also play a role in deprived countries and in rural areas. The complexity of treatment with the multiple drugs recommended and their potential interactions with non-cardiovascular drugs can also be a hurdle. Perception of guidelines and their usefulness may also play a role in the physician’s adherence.

Guideline Factors

Guidelines are often perceived as being too long and too complex, highlighting the need for concise recommendations with clear, simple flowcharts. In addition, the dissemination of guidelines through scientific channels, such as scientific societies, may differ between countries.

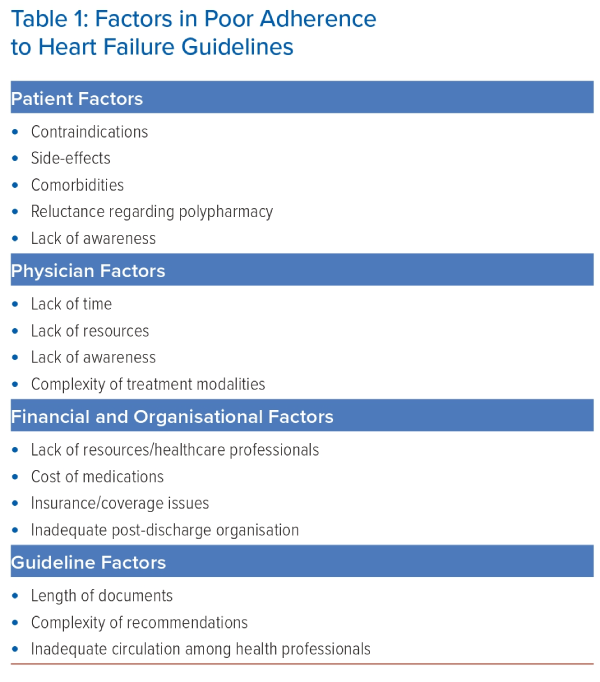

All the factors discussed above are often combined and play a major role in the insufficient implementation of guidelines; Table 1 gives a summary of them. A recent survey of cardiologists found the six most important barriers to guideline-recommended medical therapy, by descending order, were: treatment side-effects/intolerance; complexity of treatment regimen; low blood pressure; cost/reimbursement issues; kidney dysfunction; and older age.16

Impact on Clinical Outcomes

Various observational studies have shown that adherence to guideline-recommended therapies is associated with improved clinical outcomes. In the BioStat survey, a low dosage of ACEis/ARBs and of β-blockers was a strong predictor of mortality, with a particularly poor outcome in patients receiving <50% of the target dose.17

In the ASIAN-HF registry, higher dosages of ACEi/ARB or β-blockers were associated with a lower risk of experiencing the composite endpoint of all-cause death or hospitalisation for HF at 1 year compared to those not taking them; the lowest risks were observed in patients taking >50% of the target recommended dose.

In the QUALIFY registry, a score was built using both rates of prescription (in HFrEF patients without contraindications) and dosages.18 Patients with the highest score (better adherence) had a significantly lower rate of HF death and of the composite of HF death or cardiovascular mortality at 18 months.

The benefit of prescribing all recommended medications was also demonstrated in a cross-analysis that pooled data from EMPHASIS-HF (eplerenone), PARADIGM-HF (sacubitril/valsartan) and DAPA-HF (dapagliflozin), and compared patients treated with modern therapies combined with β-blockers with those receiving conventional treatment with ACEis and β-blockers. The modern therapy provided 2.7–8.3 more years of survival, without cardiovascular death or HF hospitalisation, than traditional dual therapy.19

Another argument for the need for speed after an HF hospitalisation comes from the STRONG-HF study, which showed that a rapid uptitration of recommended therapies, regardless of ejection fraction, was safe and associated with a reduction in 6-month mortality in patients hospitalised for decompensated HF.20

Proposed Solutions

To improve the situation, we need to develop simple, concise guidelines that are easily readable by all healthcare professionals and to reserve full-text documents for experts or the academic sector. This is all the more important as guidelines and position papers are the leading source of information for healthcare professionals.16

To address organisational limiting factors, disease management programmes involving cardiologists, GPs, nurses and dietitians should also be encouraged to fill the gap when a patient is discharged to prevent therapeutic inertia and reduce the risks of hospitalisation readmission and mortality. This includes the development of HF specialist centres and HF nurse training courses, since HF nurses can replace doctors in patient follow-up. The financial burden would need campaigns targeting decision-makers, urging them to offer guideline-recommended therapies at a reasonable price to HF patients in low- and middle-income countries, as well as a minimal coverage.

Patient education is also key to increasing awareness of the disease and the potential benefits of the different treatments available as well as to provide detailed diet recommendations.

Telemonitoring and, possibly, artificial intelligence could be employed to detect early signs or symptoms of decompensation and to adopt corrective measures thereby limiting the rate of rehospitalisations. However, their role to help the implementation of guideline-recommended therapies in stable chronic heart failure is unclear.

Conclusion

Despite major progress in the therapeutic management of HF, implementation of guidelines remains suboptimal. This is related to multiple factors related to patients, healthcare professionals, cost, the organisation of healthcare systems and, finally, the structure of guidelines.

Joint efforts by cardiologists, GPs, nurses and other healthcare professionals, policymakers and payers are needed to improve this situation and reduce the burden of HF.

Clinical Perspective

- Despite evidence derived from large clinical randomised trials, implementation of guidelines for the management of heart failure remains suboptimal.

- Both rates of prescription and dosages achieved for each recommended heart failure class of medication are below target.

- Reasons for poor adoption include factors related to patients (side effects, contraindications, comorbidities, age, sex and polypharmacy), economic and organisational factors (cost of medications and health insurance coverage), physicians (awareness of the goals of treatment) and guideline complexity.

- Poor adoption is associated with poor outcomes (mortality and rehospitalisation).

- Solutions include patient education, disease management programmes, telemonitoring and campaigns targeting decision-makers to offer drugs at an affordable price.