Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults (MIS-A) is an under-reported post-sequela of COVID-19 infection that usually presents 4–6 weeks after the initial infection. Patients are usually young or middle-aged and present with a myriad of signs and symptoms, specifically cardiac, neurological, gastrointestinal and dermatological involvement. Recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to diagnose MIS-A comprise clinical and laboratory evidence, including elevated inflammatory markers and recent SARS-CoV-2 infection.1–5

Case

A 36-year-old woman sought an emergency consultation due to severe chest pain characterised as continuous, sharp and non-radiating, accompanied by diarrhoea and abdominal pain localised at the epigastric area, which was not relieved with any pain medications. She reported no diaphoresis, febrile episodes or palpitations. She had a moderate COVID-19 infection 2 weeks prior to the consultation, up-to-date COVID-19 vaccination and good functional capacity. The patient had type 1 diabetes and was maintained on insulin therapy but no other known comorbidities. She was a non-smoker, did not drink alcohol and had an unremarkable family history for cardiac disease.

Upon arrival at the emergency department, the patient was conscious and coherent but in cardiac distress, haemodynamically unstable with blood pressure as low as 80/60 mmHg on both arms and was tachycardic with a pulse rate of 112 BPM. She had a normal respiratory rate of 19 breaths per minute with no desaturation, pallor or cyanosis. There was no carotid bruit with a jugular venous pressure of 8 mmHg above the sternal angle. On cardiac examination, there were distinct S1 and S2 sounds, with no heaves, thrill, murmur or S3 gallop. Pulses were full and equal on all extremities with no bipedal oedema.

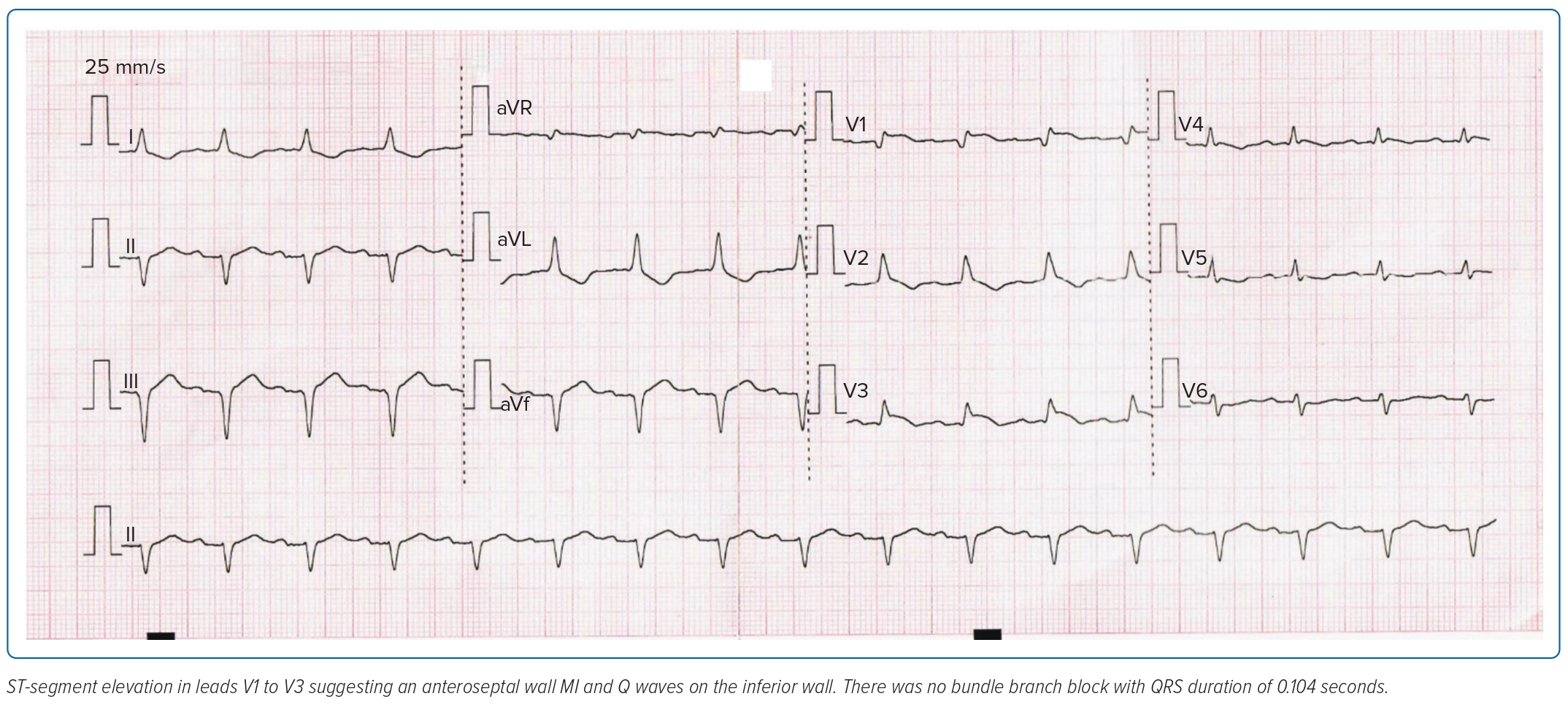

An ECG showed anteroseptal wall MI with Q waves on the inferior wall (Figure 1) with elevated cardiac enzymes (troponin T >2,000 ng/l and creatine phosphokinase 669 U/l). A repeat SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcriptase PCR assay was negative.

The patient was initially given fluid resuscitation of 1 l crystalloid solution and hooked to a low-dose dobutamine drip. She was also started on an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) regimen of aspirin 300 mg, clopidogrel 600 mg, enoxaparin 60 mg and rosuvastatin 40 mg.

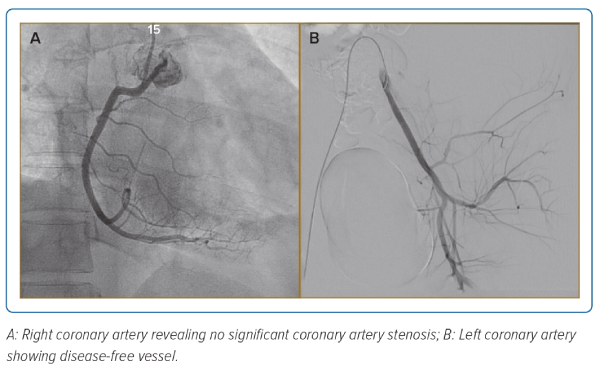

The patient underwent a coronary angiogram, which revealed no significant coronary artery stenosis (Figure 2), ruling out coronary artery disease as the cause of cardiac pathology and leading to a working diagnosis of MI with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA). Diagnosis of MINOCA is made immediately upon coronary angiography in a patient presenting with features consistent with an acute MI with the following criteria:

- a positive cardiac biomarker and clinical evidence of infarction evidenced by either symptoms of ischaemia or ECG changes suggestive of infarction, specifically significant ST-T changes, new onset left bundle branch block or pathological Q waves

- non-obstructive coronary artery on angiogram; and

- no clinically overt specific cause for acute presentation.6–8

MINOCA can be due to myocarditis, coronary or myocardial disease, pulmonary embolism or stress cardiomyopathy. Further diagnostic tests were performed to identify the underlying cause. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed hypokinesia of the entire interventricular septum and inferior left ventricular (LV) free wall from base to apex with a mildly reduced ejection fraction (EF) of 43.3%. There was also elevation of inflammatory markers, specifically ferritin (456.9 ng/ml) and C-reactive protein (CRP; 24.0 mg/l). Other pertinent findings included HbA1c 7.8% and normal amylase and lipase levels.

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were elevated at five to seven times the upper limit of normal with normal bilirubin levels. Immunological test showed an antinuclear antibody (ANA) ratio of 1:80 with a fine speckled pattern and normal complement levels. The patient was admitted to the cardiac care unit for closer monitoring.

One of the pertinent differentials to consider in similar cases is stress cardiomyopathy because it is prevalent in this specific age group with similar presenting symptoms and requires mainly supportive treatment. Triggers of stress cardiomyopathy are physical or emotional stressors that cause excessive activation of the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in increased catecholamine production, leading to endothelial injury. The classic morphological pattern of LV regional wall motion abnormality is apical hypokinesia, akinesia or dyskinesia (apical ballooning) with basal hyperkinesia.9

In the present case, there were no specific triggers of stress cardiomyopathy and the pattern of LV wall motion seen on TTE was different. The patient was assessed as MINOCA with myocarditis as the aetiology.

Discussion

As defined by WHO, a diagnosis of myocarditis is established based on histological Dallas criteria in endomyocardial biopsy. As this is an invasive test, the position statement of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Disease established diagnostic criteria for clinically suspected myocarditis consisting of clinical presentation and diagnostic criteria of newly abnormal ECG changes, myocardiocytolysis, abnormalities on cardiac imaging and tissue characterisation by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging.10

Our patient was eventually managed as having post-viral myocarditis. In about one-third of patients, MINOCA is caused by previous viral infection, specifically adenovirus, parvovirus B19 (PVB19) and Coxsackie virus.11 There are emerging data regarding SARS-CoV-2 infection causing viral myocarditis.

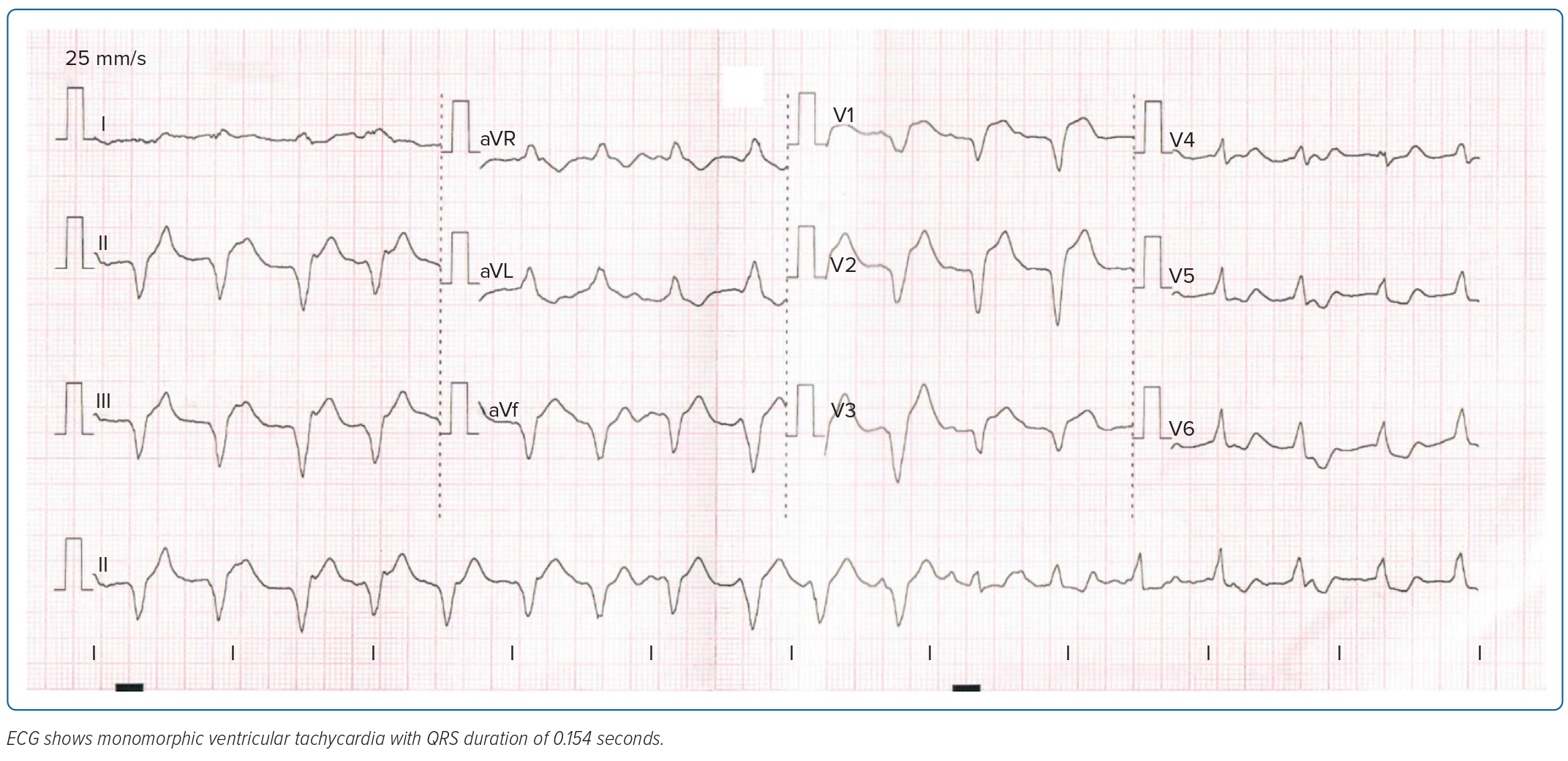

On the second day of admission, the patient was scheduled for CMR imaging, but this was deferred due to recurrence of chest pain. She was conscious with stable blood pressure, but still had febrile episodes and monomorphic ventricular tachycardia on ECG (Figure 3). The patient was initially managed as having non-sustained ventricular tachycardia and was started on an amiodarone drip. Work-up was negative for bacterial growth in both blood and urine specimens. There was persistence of elevated inflammatory markers but still no source of infection.

As the patient recently had COVID-19, was hospitalised for more than 24 hours and had no other likely diagnosis but had fever accompanied by diarrhoea on admission with elevated inflammatory markers and signs of cardiac dysfunction, she fulfilled CDC criteria for MIS-A, and was consequently started on IV immunoglobulin (IVIg) and steroid pulse therapy.12 As there is a paucity of data concerning the management of MIS-A, recommendations were adapted from those in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). In a study of MIS-C by Patel et al., IVIg ameliorates inflammation by targeting interleukin-1β, which is expressed by activated neutrophils.5

Our patient had a good response to treatment and on the 10th hospital day a repeat TTE showed improvement in overall LV systolic function and an increase in LVEF to 55%. There were also decreases in inflammatory markers (ferritin 180.8 ng/nl and CRP 12.0 mg/l). The patient was stable throughout her hospital stay. Outpatient follow-up two weeks after discharge revealed patient improvement with no recurrence of chest pain. She returned to work with complete resolution of symptoms. Diagnostic tests showed an increase in EF to 60% with resolution of hypokinesia in the entire interventricular septum and LV free wall. ALT and AST levels returned to baseline. Other routine diagnostic tests were all normal.

Conclusion

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has a high cumulative incidence and infectivity rate, causing great burden across the world. However, there is a paucity of data regarding the complications that the disease may cause. Knowledge of these issues is essential to a physician.

Based on the current and most recent available recommendations from the MIS-A case definition by the CDC, our patient satisfied all the given criteria, namely recent SARS-CoV-2 infection and fever at the time of presentation accompanied by severe cardiac illness presenting as myocarditis and EF <50% with secondary clinical criteria of hypotension and diarrhoea, which was further strengthened by laboratory evidence of elevated inflammatory markers (CRP and ferritin). The characteristics of MIS-A are not well understood, but can be attributed to endotheliitis or autoimmune disease, in association with other hyperinflammatory phenotypes and other consequences of COVID-19. There are currently no recommendations on how MIS-A causes MINOCA, but we hypothesise that it could be due to an inflammatory response causing involvement of the myocardium resulting in reduced cardiac function.

The collaborative efforts of subspecialties, in this case early recognition of MIS-A and prompt administration of necessary treatment, led to a decreased burden of disease and a good overall prognosis. Effective strategies that may lead to favourable outcomes may include adequate clinical knowledge of MIS-A, a high index of suspicion among patients with COVID-19, prompt intensive care admission and immediate corticosteroid treatment.

Clinical Perspective

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-A) is a rare but severe complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection and can occur at around 2–12 weeks after the initial infection.

- Diagnostic criteria include a myriad of symptoms, specifically cardiac, neurological, gastrointestinal and dermatological involvement accompanied by laboratory evidence showing elevated inflammatory markers and a recent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- Treatment for MIS-A includes corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin and immune modulators.

- Early recognition of MIS-A and prompt administration of necessary treatment leads to decreased burden of disease in the patient and a better overall prognosis.