Obesity has become a widespread problem in the Asia-Pacific region, with an alarming rate of increase in its prevalence, notably in countries such as China and India. Obesity is associated with a significant healthcare burden resulting from its associated comorbidities, especially cardiovascular diseases. National guidelines on the management of obesity are available in some countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Newer anti-obesity pharmacotherapies have become available and show efficacy in weight reduction. In this review, we summarise the situation and the burden of the obesity epidemic in the Asia-Pacific region, discuss the diagnosis and risk factors and review the management strategy for patients with obesity.

Epidemiology of Obesity in the Asia-Pacific Region

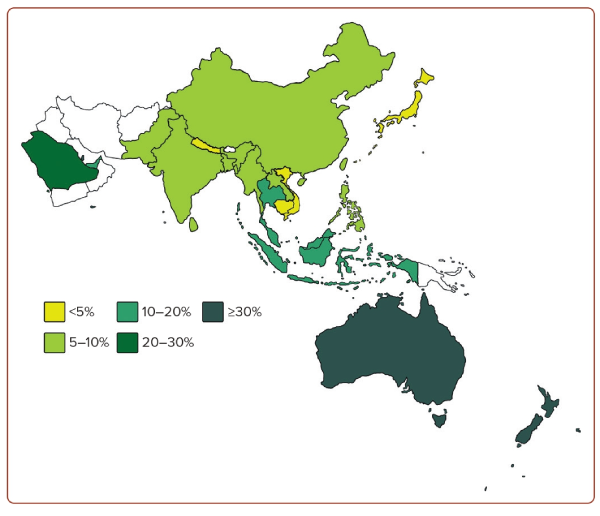

Obesity represents an excessive accumulation of body fat, which leads to impaired health and an increased risk of long-term health complications and mortality.1 Obesity has become a global pandemic. According to the World Obesity Atlas 2023, the global prevalence of obesity (defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m²) is expected to rise from 14% in 2020 to 24% by 2035. It is estimated that more than 800 million adults are affected by obesity. The economic impact is estimated at 2.2% of the global gross domestic product.2 The Asia-Pacific region – comprising over 50 countries across Oceania and the Pacific, South and Southeast Asia, Northeast Asia and Central Asia – contributes to nearly half of the world population.3 Figure 1 shows the prevalence of obesity in the region. In recent years, there have been major concerns over the rising prevalence of obesity in the Asia-Pacific regions, contributed to by the adoption of westernised lifestyles.4,5 The rise is particularly alarming in China and India.5,6 Taking China as an example, it was once considered to have one of the leanest populations in the world. The number of Chinese people with obesity was below 0.1 million in 1975, rising to 43.2 million in 2014, accounting for 16.3% of the global obesity burden.7 Similarly, the number of Indian people with obesity was 0.4 million in 1975, rising to 9.8 million in 2014.7 Hence, it is important to review the latest situation of obesity in the Asia-Pacific region.

Australia has a relatively high prevalence of obesity, reaching 31.3%, as reported in the Australian National Health Survey 2017–18.8 A high prevalence of 20–40% has also been recorded in West Asian countries, such as Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.9 Among Southeast Asian countries, Malaysia records the highest prevalence of obesity, at approximately 20% in the National Health and Morbidity Survey 2019.10 In contrast, the prevalence of obesity in Singapore was 10.5% according to the National Health Surveillance Survey in 2019–2020 by the Ministry of Health.11 Interestingly, there were notable inter-ethnic differences among people in Singapore: 20.7%, 14.0% and 5.9% of people of Malay, Indian and Chinese ethnicity, respectively, were considered obese.12 There are slight variations in the prevalence of obesity in different Chinese populations. In China, the estimated prevalence of obesity was 8.1% in 2018 according to the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, whereas the prevalence was 6.9% in Hong Kong based on the Population Health Survey 2020–2022.13,14 In Taiwan, the prevalence was 8.2% from the Nutrition and Health Survey in 2013–2014.15 In South Asia, the prevalence was 5.5% and 5.4% in India (from the National Family Health Survey 2019–2021) and Bangladesh (from the National STEPS Survey in 2018), respectively.16,17 The prevalence of obesity was reported to be lowest in Japan, at 4.5%, according to the National Health and Nutrition Survey in 2019.18

Childhood obesity has also become another major concern worldwide.19 Countries in the Asia-Pacific region are most vulnerable to the childhood obesity crisis because of rapid economic development and urbanisation, accompanied by trends towards consuming convenient, over-processed junk food. In Asia, countries such as China, Indonesia and India have reported an alarming rapid increase in childhood and adolescent obesity rates over the past decades. According to World Obesity Federation, the prevalence in China increased from 0.9% in 2002 to 8.8% in 2015, and in Indonesia from 1.8% in 2007 to 4.6% in 2015. Elsewhere, in India, the prevalence of obesity increased from 9.8% to 11.7% among adolescents between 2006 and 2009.20

Diagnosis of Obesity

BMI, a proxy for measuring body fat, is widely used to define obesity.21 Epidemiological studies have shown that a high BMI meeting the definition of obesity correlates with increased health-related complications and all-cause mortality, including the largest study by the Global BMI Mortality Collaboration.22 While BMI is a practical and convenient measure of obesity in clinical settings, there are several shortcomings. These include the inability to distinguish between excess fat, muscle or bone mass; the variations in the cardiovascular and metabolic manifestations among individuals when obesity is defined solely based on BMI; and the inability to account for sex, age and ethnic differences in differences in body fat composition by BMI.23

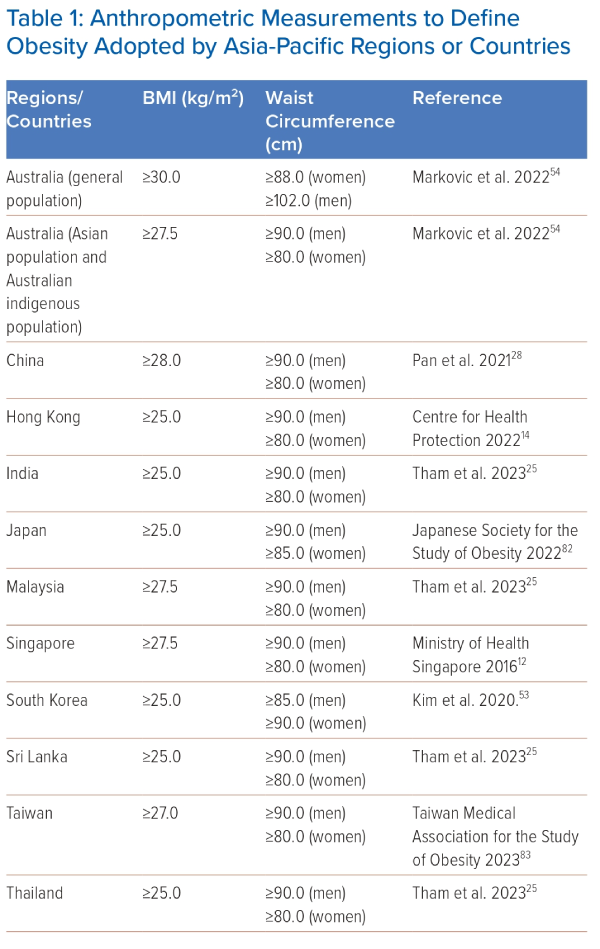

The international definition for obesity is BMI ≥30 kg/m2, based on data derived mainly from white populations. Asian populations have a lower body weight compared with white populations. However, Asian populations tend to have a higher amount of body fat at a given BMI compared with white populations, especially visceral adipose tissue.24 Ethnic differences in body composition have been recognised, and Asian populations develop obesity-related morbidities, including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, at a lower BMI than the international definition of obesity.21 A lower BMI cut-off for obesity has been recommended for Asian populations to improve the identification of individuals at risk of cardiometabolic diseases.25 Most countries in the Asia-Pacific region apply a BMI threshold of 25 kg/m2 or 27.5 kg/m2 to define obesity. Table 1 summarises the BMI cut-off points in the Asia-Pacific region.

Measuring waist circumference (WC) can help to assess visceral adiposity, which has been demonstrated to correlate with a range of cardiometabolic complications.24 There is also a higher prevalence of abdominal obesity in Asian populations, particularly South Asians, than in white populations.24 The International Diabetes Federation criteria for metabolic syndrome recommends using an ethnic-specific threshold for WC as a surrogate marker of abdominal obesity.26 The WHO STEPwise approach to Noncommunicable diseases risk factor surveillance (STEPS) manual recommends that WC should be measured at the midpoint between the superior iliac crest and the lower margin of the last rib in a horizontal plane.27 Most countries in the Asia-Pacific region apply a WC threshold of ≥90.0 cm for men and ≥80.0 cm for women to define central obesity (Table 1).

Risk Factors for the Development of Obesity

The cause of obesity is most commonly multifactorial. From the individual perspective, the development of obesity is attributable to the energy surplus resulting from dietary factors, levels of physical activity and genetic predisposition. This, in turn, is driven by the obesogenic environment under the influence of various socioeconomic and political factors.28 Over the years, lifestyle has changed substantially in the Asia-Pacific region, with rapid socioeconomic developments. There has been a shift from traditional diets to eating patterns that include more high-fat, high-energy foods and drinks.28 For instance, a study based on the China Health and Nutrition Survey packages from 1997 to 2011 revealed a switch in dietary patterns in China from a predominantly plant-based diet to a western-style diet high in fat and animal-based foods with increased fat intake.29 Concomitantly, there is a significant reduction in physical activity following the shifts in occupational and recreational patterns.3 Objective quantification using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire revealed the important issue of lack of physical activity.30

An international prevalence study of physical activity in 20 countries, including the Asia-Pacific region, recorded a rather high percentage (up to 40%) of low levels of physical activity in areas, such as Japan and Taiwan.31 While these lifestyle changes can – in part – explain the increasing prevalence of obesity in the Asia-Pacific region, this is further compounded by the obesogenic environment brought about by economic developments and urbanisation. Economic globalisation and trade liberalisation promotes the mass production and marketing of foods with high added values, with increasing availability and accessibility to cheap but palatable unhealthy foods and sugar-sweetened beverages.32 Technological advances also encourage a more sedentary lifestyle. As a result of production automation, there is a reduction in work-related physical activity. Similarly, the increasing household use of electrical and electronic products promotes a sedentary lifestyle.33

Disease Burden of Obesity: Comorbidities and Complications

Individuals with obesity are predisposed to various obesity-related disorders, including several important cardiometabolic diseases. There is a positive linear correlation between obesity and type 2 diabetes. Excess adiposity likely contributes to insulin resistance and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction.23 A meta-analysis of Mendelian randomisation studies showed that genetically predicted high BMI was associated with type 2 diabetes, with an OR of 2.03 for every 1 SD increase in BMI.34 The China Kadoorie Biobank cohort study reported that each SD higher BMI was associated with 98% and 77% higher risks for diabetes in men and women, respectively.35 Obesity also contributes significantly to hypertension, at least in part related to increased activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone and sympathetic nervous systems.36 Studies in different populations have demonstrated a nearly linear relationship between BMI and systolic blood pressure.37 A multicentre study in China showed that obese individuals had a RR of 1.28 for hypertension upon 8 years of follow-up.38

Furthermore, obesity is associated with dyslipidaemia related to insulin resistance and a lower likelihood of achieving optimal LDL cholesterol targets.39 Dyslipidaemia in obese individuals is characterised by high triglyceride levels, low HDL cholesterol levels with reduced cholesterol efflux capacity, and increased LDL cholesterol levels, with predominantly small dense LDL particles, which are particularly atherogenic. As a result, obesity is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease, heart failure and stroke.40 The Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration, pooling data from 44 cohort studies in the region, showed that obesity was associated with an adjusted HR of 1.17 for fatal coronary artery disease and 1.19 for fatal ischaemic stroke.41 The deleterious effect of obesity leads to haemodynamic and morphological changes in the cardiovascular system, even among individuals without overt cardiac diseases. These changes include left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy and dysfunction, increased LV end-diastolic dimensions, increased circulating blood volume, increased cardiac output, and a decreased stroke work/LV end-diastolic pressure index.42 The adverse effects of obesity on the cardiovascular system can be substantially reversed by weight reduction.42

Interestingly, in the field of cardiovascular medicine, there is evidence suggesting an ‘obesity paradox’ in which obese patients have a more favourable prognosis in certain diseases, such as heart failure, valvular heart disease and stable coronary artery disease.43 This phenomenon seems to be observed only when obesity is classified by BMI, whereas using newer obesity indices that do not incorporate weight still show that greater adiposity is associated with higher risk of heart failure hospitalisation.43,44 These data suggest that these newer anthropometric measurements (such as waist-to-height ratio, relative fat mass and body roundness index) are better indicators of adiposity. These indices, incorporating WC and height, can more accurately reflect intra-abdominal fat and account for sex- and race-based differences in stature and skeletal weight, whereas measurements such as the overall weight or BMI may be confounded by fluid retention in the context of heart failure and unintentional weight loss because of other illnesses.43 In fact, studies show that malnutrition can coexist with obesity, and malnutrition is associated with unfavourable prognosis regardless of obesity status.45

Recently, there has been increasing recognition of the association between obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).7 Obesity is associated with ectopic fat deposition in the liver.23 The pooled prevalence of NAFLD in Asian countries has been estimated at 27.4%.46 The secular trends of obesity and NAFLD are rising in Asia.7 For example, the prevalence of NAFLD rose from 18.2% in 2000–2006 to 20.9% in 2010–2013 in China.47 It was estimated that 63.5% of biopsy-proven NAFLD patients had non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, which has emerged as the most common cause of cryptogenic cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.46

There is also sufficient evidence to show that obesity is related to at least 13 types of cancer.48 This may be partly mediated through chronic inflammation and hyperinsulinaemia. Large cohort studies in China have shown the association between obesity and overall cancer risk. Specific types of cancer have been associated with obesity as well. The China Kadoorie Biobank study showed that risks of liver, pancreatic and colorectal cancer increased with higher BMI.38 A Korean population-based study demonstrated the significant association between obesity and the risk of colorectal and kidney cancers in men, and the risk of endometrial, postmenopausal breast, liver, gallbladder, colorectal, ovarian, kidney and pancreatic cancers in women.49 In addition, obesity is associated with mechanical complications, such as osteoarthritis and obstructive sleep apnoea.37

Obesity not only increases the risk of having multiple obesity-related comorbidities in a dose-dependent relationship, but is also associated with an increase in all-cause mortality as shown by the Global BMI Mortality Collaboration.22,50 The association between BMI and mortality is not linear. Most studies have identified a U-shaped relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality, with the nadir of the curve observed at BMI 23–24 kg/m2 among never smokers, 22–23 kg/m2 among healthy never smokers, and 20–22 kg/m2 with longer durations of follow-up.51 This U-shaped relationship is also seen in the Asia-Pacific region.38

Management of Obesity in the Asia-Pacific Region

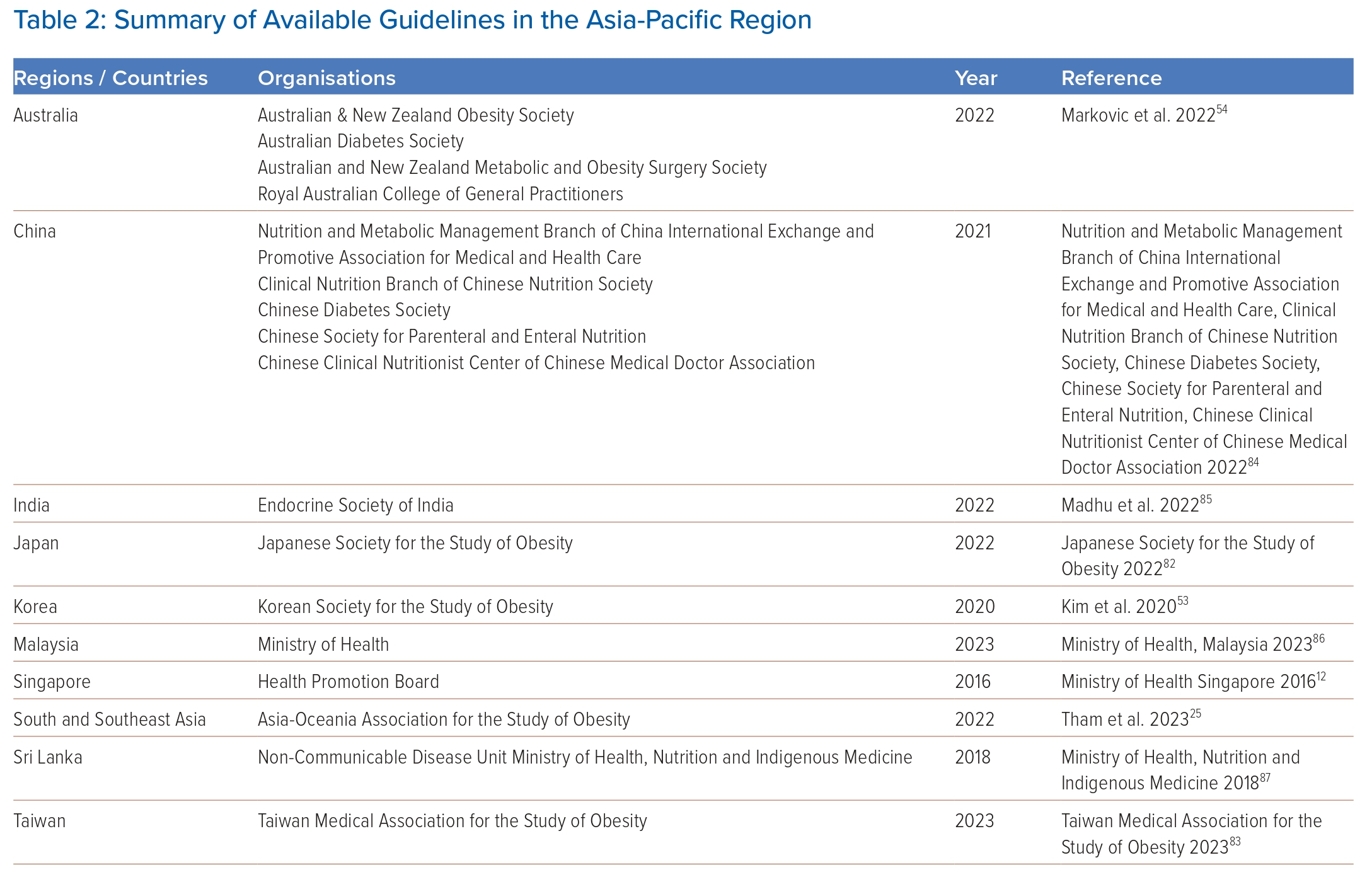

National treatment guidelines have been developed in some countries in the Asia-Pacific region (Table 2), and a recent consensus on the care and management of obesity in South and Southeast Asia formulated by a group of obesity specialists from the region has been released.25 Here, we broadly summarise the suggested strategies for the management of obesity.

Targets of Weight Loss

Achieving weight loss is the key to attain amelioration or remission of obesity-related complications, and multidisciplinary collaborative care is vital to achieving the optimal outcome. In addition to the physician, dietician or nutritionist, a physiotherapist, psychologist or psychiatrist and obesity nurse or educator should be included.25,52 Setting the target weight loss requires a thorough discussion with patients, along with establishment of a good therapeutic rapport, and frequent consultations may be required.

Most guidelines recommend an initial 5–10% weight loss over 6 months as an appropriate short-term treatment goal.11,25,53 If this is not attainable, prevention of further weight gain as an alternative may be recommended. In the long term, patients should be encouraged to lose more weight if possible.11 Some suggest that the target weight loss may be set according to the initial BMI, and BMI thresholds may differ between ethnic groups.54 For example, in the Australian guideline, the following target weight loss is suggested: for people with BMI 30–40 kg/m2 or abdominal obesity without complications, 10–15% weight loss is recommended, which can be achieved through supervised lifestyle interventions or pharmacotherapy; for people with BMI 30–40 kg/m2 or abdominal obesity with complications, or BMI >40 kg/m2, 10–15% weight loss is recommended, which can be achieved through intensive lifestyle interventions, pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery; and for people with BMI >40 kg/m2 and complications, a target weight loss of >15% is recommended and they should be referred to specialist care and be managed through a combination of lifestyle interventions, pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery.54

Lifestyle Interventions

Lifestyle interventions are critical components in the management of obesity and cover three main aspects: medical nutrition therapy, physical activity and behavioural changes. In terms of medical nutrition therapy, reduced caloric intake is the key. A diet contributing to a daily caloric deficit of at least 500 kcal below the estimated daily energy requirements should be recommended.52,53 Although various specific diets, such as ketogenic diets, have emerged with claimed benefits in weight loss, they may be associated with significant alterations in macronutrients. Clinicians should advise patients to focus on achieving caloric restriction rather than specific diets.55

Physical activity is vital to achieve weight loss. Physical activity combined with dietary interventions is more effective than dietary intervention or physical activity alone. It also brings about weight-independent health benefits, such as reducing cardiovascular risks. The recommendations are for at least 150–300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or 75–150 minutes of vigorous aerobic exercise a week, together with strength training exercises for 2 days or more in a week.52 Individuals who are inactive should gradually step up the intensity of exercise.

Behavioural changes are the third crucial component in achieving weight loss. Developing a habit is essential to sustain weight loss in the long term. The relevant elements in this aspect include education, goal setting, self-monitoring (weight, food intake and exercise), stimulus control and stress reduction.52 When treating obesity, it is crucial to identify and treat any concurrent eating disorders, such as binge eating. Individuals with obesity should be advised to quit smoking and drinking.53

Pharmacotherapy

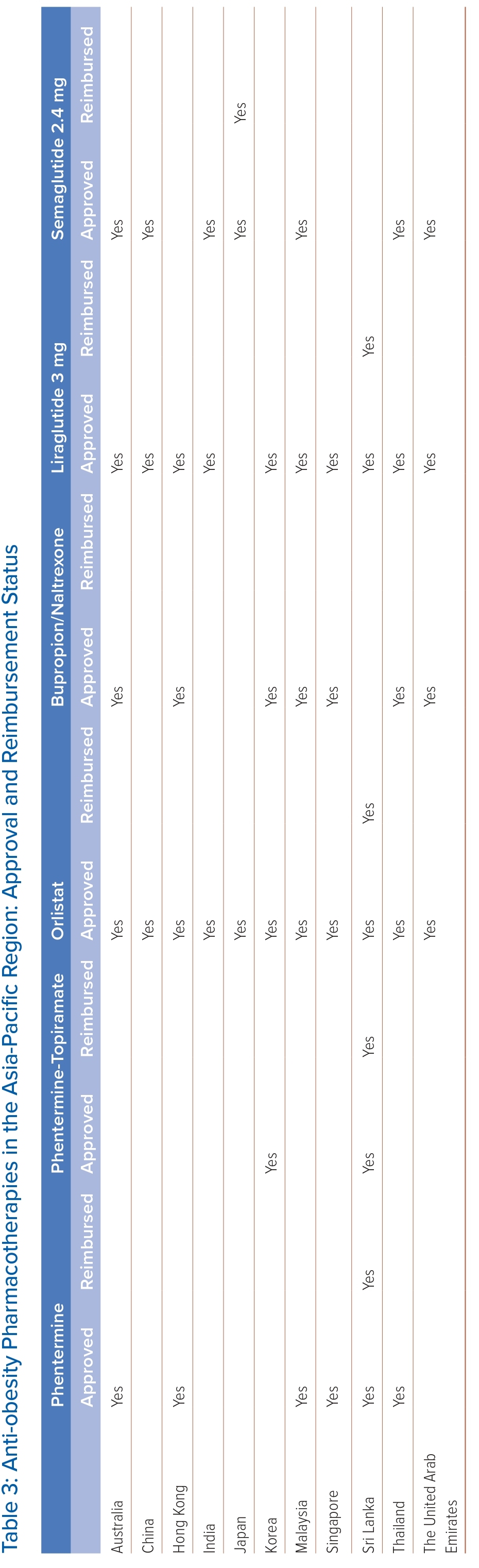

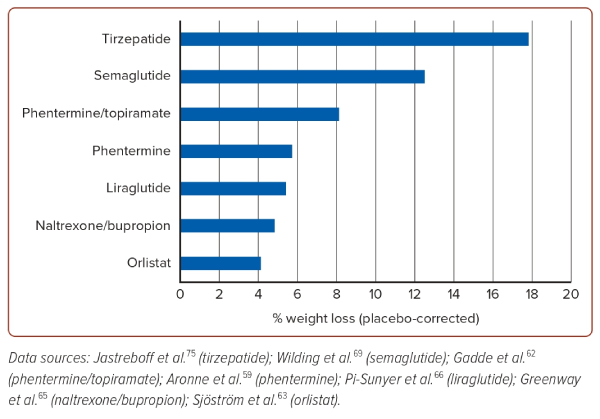

Anti-obesity pharmacotherapies are used when initial dietary and lifestyle interventions fail to reach the weight-loss target. These medications target peripheral and central pathways to decrease energy intake by reducing appetite and increasing satiety. Table 3 summarises the pharmacotherapies approved and reimbursed for obesity in the Asian-Pacific region. In some countries, the use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), such as liraglutide and semaglutide, is reimbursed for treatment of diabetes only but not for obesity. Following the international guidelines, all the anti-obesity pharmacotherapies listed in Table 3 may be considered in patients with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 or ≥27 kg/m2 in the presence of obesity-related complications.56 Nonetheless, some guidelines propose lower BMI thresholds, reflecting that Asian people develop obesity-related complications at lower BMI than white people.25 For example, the 2009 consensus statement recommends pharmacotherapy in Asian Indian adults with BMI ≥27 kg/m2 or ≥25 kg/m2 in the presence of complications, while the South Korean guideline published in 2020 suggests a BMI threshold of 25 kg/m2.53,57 The choice of anti-obesity pharmacotherapy is individualised based on the desired weight loss, accessibility and cost, route of administration and adverse effect profile. Their efficacies are shown in Figure 2. Currently available treatments can also be divided into those with and without additional cardiovascular benefits. Cost is one of the major barriers to access of the newer more potent anti-obesity pharmacotherapies, especially since long-term treatment is usually required.

Phentermine is a centrally acting adrenergic agonist that suppresses appetite. As monotherapy, it is approved for short-term use (<12 weeks) in obesity and is associated with 5.7% placebo-corrected weight loss.58 Adverse effects are related to its impact on the sympathetic nervous system, including hypertension, tachycardia, dry mouth and insomnia. It should not be used in patients taking anti-depressants, or in those with coronary artery disease, arrhythmia or uncontrolled hypertension.59

Topiramate is an anti-convulsant with the effect of appetite suppression. In three randomised controlled trials (EQUIP, CONQUER and SEQUEL), a combination of phentermine and topiramate was associated with up to 8.1% placebo-corrected weight loss.59,60 Phentermine combined with topiramate is approved for the long-term treatment of obesity with long-term safety and efficacy demonstrated in the SEQUEL study with a duration of 108 weeks.59 Given the associated metabolic acidosis, topiramate should be used cautiously in patients with kidney stones. It has also been reported to be associated with acute glaucoma.61 Women of childbearing age taking this drug should be advised on effective contraception because of the risk of oral clefts from exposure to topiramate in utero.59 Drug withdrawal should be done gradually to avoid seizures, particularly in patients on the highest doses.

Orlistat inhibits gastric and pancreatic lipase, reducing fat absorption by up to 30%. The use of orlistat has been reported to be associated with 4.1% placebo-corrected weight loss over 1 year.62 The XENDOS study supports the safety of orlistat over 4 years.63 Adverse effects of the medication include flatulence and steatorrhoea, which may limit drug adherence. Adopting a low-fat and high-fibre diet can reduce some of the adverse effects.11 When used in the long term, orlistat may lead to deficiencies in fat-soluble vitamins and the development of oxalate kidney stones.54

Naltrexone/bupropion consists of naltrexone (an opioid antagonist) and bupropion (a dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor) that acts centrally on the hypothalamic hunger system and the mesolimbic reward centres of the brain. In the landmark COR-I study, the use of naltrexone/bupropion was associated with 6.1% weight loss, compared with 1.3% weight loss in the placebo group.64 Its main adverse effects include nausea and vomiting, which can be reduced by a gradual up-titration of the dosage. It is contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled hypertension, seizure disorders, use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors, eating disorders and drug or alcohol withdrawal.11

Pharmacotherapy with Additional Cardiovascular Benefits

GLP-1 RAs are an important class of anti-obesity pharmacotherapy. They act on the hypothalamus leading to increased satiety, decreased appetite and delayed gastric emptying. Liraglutide and semaglutide are the two agents currently approved for the treatment of obesity. Common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, constipation and diarrhoea, which may be reduced by gradual dosage titration. GLP1-RAs are contraindicated in individuals with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 and pregnancy.59 Liraglutide 3 mg was evaluated in the SCALE study among patients with obesity, which showed a weight loss of 8.0% with liraglutide compared with 2.6% in the placebo group over 56 weeks.65 There is evidence suggesting that clinically relevant weight loss may be achieved at lower doses of liraglutide in Asian populations. A study in Japan including patients with diabetes using doses of liraglutide of 0.3–0.9 mg daily showed weight loss of 5% at 12 months and 4% at 24 months.66 Another study in Taiwan including patients without diabetes using liraglutide 0.6 mg or 1.2 mg daily showed a similar weight loss of 6.4% for 0.6 mg and 5.6% for 1.2 mg.67

Semaglutide 2.4 mg was evaluated in the STEP trials among patients with obesity, which showed a weight loss of 14.8% with semaglutide compared with 2.4% in the placebo group in STEP-1.68 STEP-8 compared the weight loss associated with the use of semaglutide 2.4 mg and liraglutide 3.0 mg among patients with overweight/obesity. The study revealed a 15.8% weight loss with semaglutide, significantly higher than the 6.4% weight loss with liraglutide.69 Semaglutide is a major breakthrough in the treatment of obesity as the degree of weight loss achieved is nearly twice that seen with other approved anti-obesity treatments. Furthermore, this class of agents have demonstrated cardiovascular protective effects in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Both liraglutide and semaglutide reduced the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events among the population with type 2 diabetes in large randomised controlled trials – LEADER and SUSTAIN-6 – respectively.59,70,71

The cardiovascular effects of semaglutide in patients with obesity have been evaluated in the SELECT trial. Results from the SELECT trial showed that once weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg significantly reduced the risk of the primary outcome of cardiovascular death, MI or stroke by 20% in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease and overweight or obesity, but who did not have diabetes. Semaglutide decreased body weight by 8.5% in the trial and also reduced the progression to diabetes.72 In patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and obesity, semaglutide 2.4 mg significantly reduced weight and improved heart failure symptoms and exercise function in the STEP-HFpEF trial.73

Emerging Therapies

Tirzepatide is an injectable dual GLP-1 receptor and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor agonist approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Given its potent weight loss properties, tirzepatide is being evaluated for the treatment of obesity and has been granted fast track designation by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In the SURMOUNT-1 trial of 2,539 participants with obesity, tirzepatide was associated with 15% weight reduction with 5 mg weekly doses, 19.5% with 10 mg doses and 20.9% with 15 mg doses, in contrast to the 3.1% weight loss with placebo.74 The most commonly reported adverse effects are gastrointestinal, such as nausea or diarrhoea. There are data available on the use of tirzepatide among patients with diabetes in the Asia-Pacific region. The SURPASS J-combo trial showed an impressive weight loss of 5.1% in the 5 mg group, 10.1% in the 10 mg group and 13.2% in the 15 mg group.75 Consistent with the results from the SURPASS J-combo trial, the sub-analysis of the East Asian participants from the SURPASS trial programme also found tirzepatide as safe and effective as in the whole study population.76 The FDA approved tirzepatide for chronic weight management in adults with obesity in November 2023.

Surgical Management: Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery

Bariatric surgery has a proven role in achieving sustained weight loss, improving obesity-related comorbidities and reducing mortality. Bariatric surgery mainly addresses weight loss, whereas metabolic surgery focuses on improving type 2 diabetes.77 Bariatric surgery can be divided into restrictive, malabsorptive or mixed procedures. Restrictive techniques decrease stomach size, leading to easier satiety, such as sleeve gastrectomy. Malabsorptive procedures bypass segments of the bowel, causing a certain degree of macronutrient malabsorption, such as duodenojejunal bypass. Mixed interventions combine restriction and malabsorption. Examples include Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and biliopancreatic diversion.77 Worldwide, sleeve gastrectomy and RYGB are the most commonly performed procedures (53.6% and 30.1% of total bariatric surgeries, respectively, in 2016).78

The Asia-Pacific Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Society summarised the current status of bariatric/metabolic surgery in the Asia-Pacific region after meeting in Tokyo in 2018.9 In many East and Southeast Asian countries, the BMI threshold for bariatric surgery is ≥35 or ≥37 kg/m2, and that for metabolic surgery is ≥27.5 or ≥32 kg/m2 in patients with diabetes or two other obesity-related diseases. In West Asia and Australia, the BMI threshold for bariatric surgery is higher (≥40 or ≥35 kg/m2 with obesity-related disease), and that for metabolic surgery is not always defined.9

Studies specifically among Asian populations show that bariatric surgery is effective and safe.79 A Japanese multicentre retrospective survey between 2005 and 2015 revealed a 20–30% weight loss over 5 years after bariatric surgery. At 3 years post-operatively, the remission rate of obesity-related comorbidities was 78% for diabetes, 60% for hypertension and 65% for dyslipidaemia.80 Careful postoperative surveillance is essential for possible complications requiring reoperation, psychiatric disorders and nutritional problems, such as iron deficiency and osteoporosis. These require a concerted effort from a multidisciplinary team.

Overall, access to bariatric surgery in the region has increased.9 Sleeve gastrectomy and RYGB accounted for 69% and 10% of bariatric surgeries, respectively, in the Asia-Pacific.79 However, according to a recent survey, several problems still remain. These include the lack of awareness and comprehension, public insurance coverage, as well as training and national registries.12 With the emergence of highly effective medical anti-obesity treatments, such as semaglutide and tirzepatide, the positioning of bariatric surgery in the treatment algorithm for patients with obesity will likely be modified in the future.

Population-level Approaches to the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity

Individuals with obesity are often stigmatised and obesity is frequently viewed by society with disdain rather than compassion. The notion that obesity is a chronic disease, such as diabetes and hypertension, is not widely recognised nor accepted. It is not the fault of the individuals with weight issues. Prejudice has begotten a lack of action, despite clear evidence of the economic and social, let alone health benefits, of sustained recognition and implementation of national strategies to address it.

The Asia-Pacific region is culturally diverse, and there are differences in socioeconomic and political factors between nations, as well as between rural and urban areas within countries. Healthcare systems vary widely and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. A concerted multinational population approach is required, with political and social advocacy to remove the stigma and address obesity as one of the immediate health threats to our region. The difficulties faced by low-income families must not be overlooked, and individuals with obesity should be able to receive treatment and support, even in low- and middle-income countries. As part of this strategy, the fundamental rights of all individuals to have access to housing, food safety and healthy options at affordable prices need to be addressed. The prevention of obesity is important and would involve public health initiatives, novel interventions like sugar tax and regulation of food advertising. Government subsidy of medical assessment, management, interventions and medications specifically for the purpose of obesity treatment is required together with investment in the research and development of new therapeutics and the evidence to support it. Implementation science and community engagement can help to make a sustained impact on societies’ long-term struggles with obesity.

Conclusion

The obesity pandemic has reached the Asia-Pacific region, and obesity is posing a significant healthcare burden to the region from its associated comorbidities. National guidelines on the management of obesity are available in some countries in the Asia-Pacific region, showing that the problem of obesity is being recognised by healthcare professionals and government bodies. While obesity is increasingly being acknowledged as a disease entity, continuous effort is still necessary to ensure sufficient awareness. Anti-obesity pharmacotherapies and bariatric surgeries with proven efficacy are available. Nonetheless, the accessibility and reimbursement criteria are potential issues in tackling obesity. Furthermore, to halt the progression of the obesity pandemic, intervention at the population level with implementation of relevant public health policies with an emphasis on prevention is necessary.81–86

Clinical Perspective

- There is an escalating obesity epidemic in the Asia-Pacific region, along with a rapid rise in childhood obesity.

- Differences exist in diagnostic criteria, management strategies and treatment accessibility between countries in the region.

- There are major challenges in prevention and in access to anti-obesity interventions.