Tuberculosis (TB) is a rare cause of constrictive pericarditis in the developed world, accounting for <5% of all cases.1 In countries where TB is endemic, tuberculous pericarditis is the most common manifestation of TB in the cardiovascular system and pericardial constriction can still occur in up to 8% of affected individuals despite anti-TB chemotherapy.2,3

Case Presentation

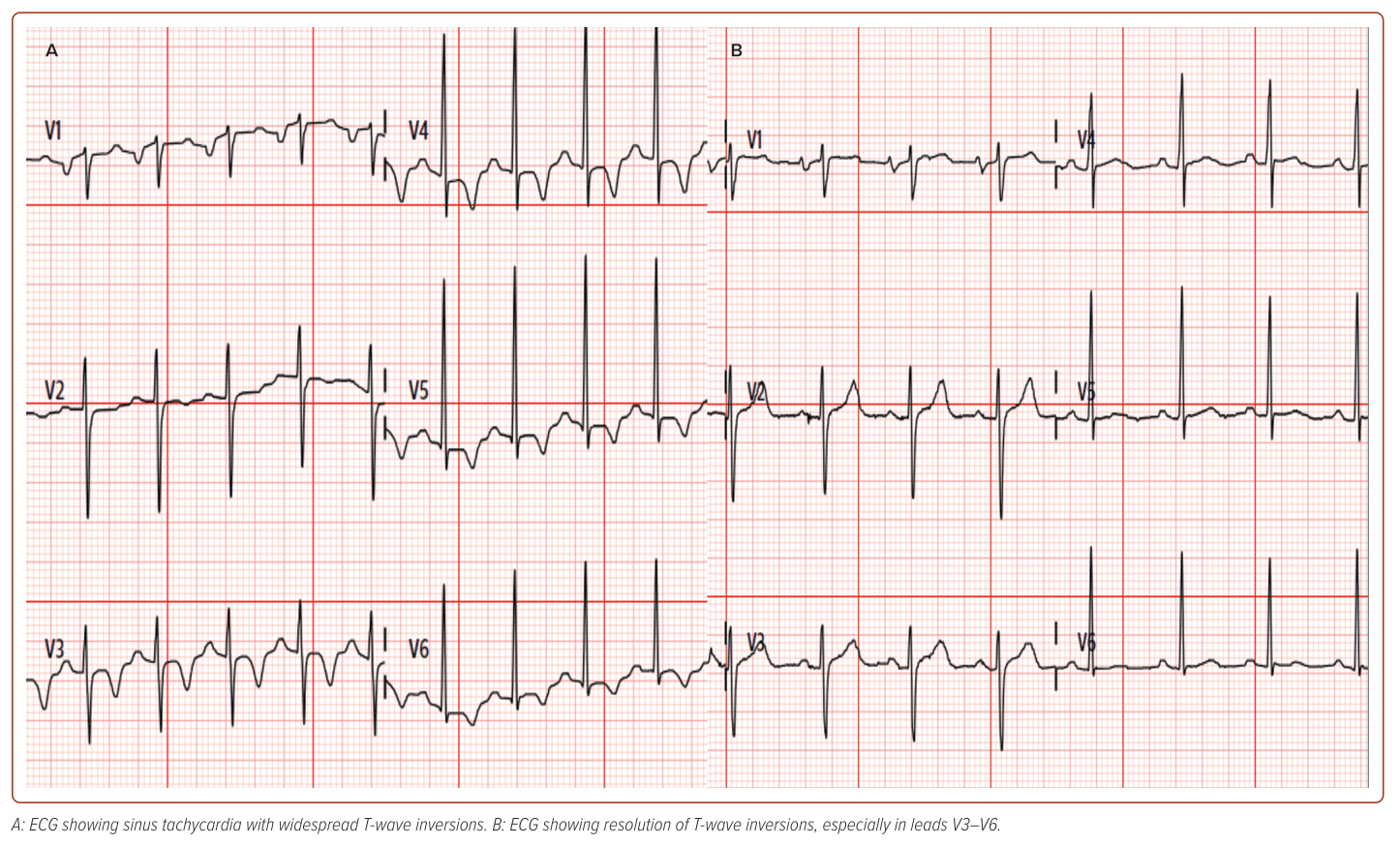

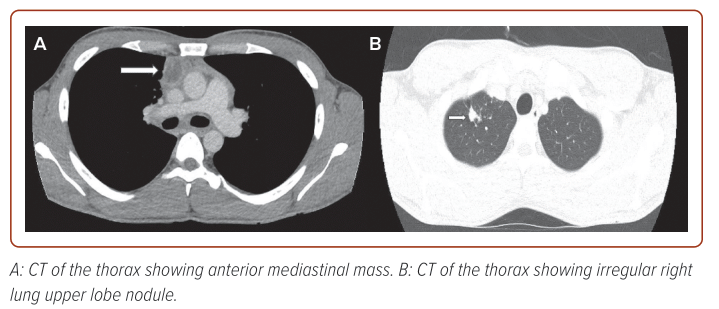

A 27-year-old man with no significant previous medical history, presented with atypical chest pain and sinus tachycardia which he had been experiencing for 1 week. His physical examination was unremarkable. His resting ECG showed sinus tachycardia with widespread T-wave inversion (Figure 1A). His initial blood tests showed raised troponin T (29 ng/l), total white cell count (10.5 x 109/l) and D-dimer (5.4 mg/l). A CT pulmonary angiogram was performed to exclude pulmonary embolism (PE). The CT did not show PE, instead there was an anterior mediastinal mass (Figure 2A) with mediastinal adenopathy and an irregular nodule in the upper lobe of the right lung (Figure 2B)

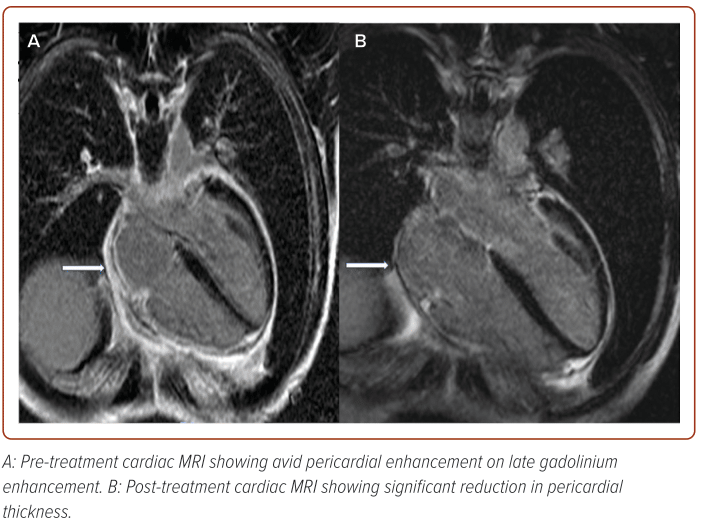

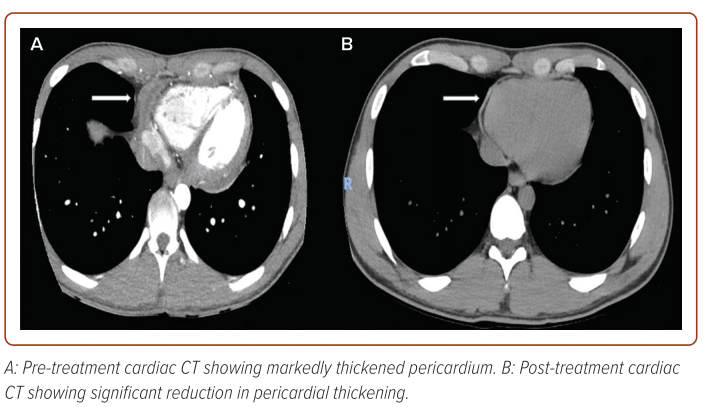

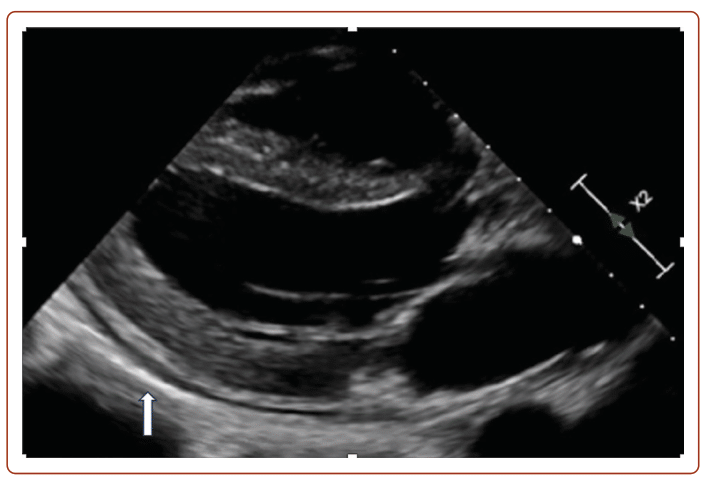

A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed septal bounce, annulus reversus, a thickened and hyperechoic pericardium along the lateral aspect of the left ventricular wall (Figure 3), which was suggestive of constrictive pericarditis. Cardiac MRI reaffirmed diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis with imaging findings of avid pericardial enhancement on late gadolinium enhancement (LGE; Figure 4A) and exaggerated bowing of the interventricular septum towards the left ventricle during inspiration (Supplementary Video 1). A subsequent CT coronary angiogram study was performed which also revealed a markedly thickened pericardium (Figure 5A) with normal coronary arteries. It was important to exclude obstructive coronary artery disease as the cause of the patient’s symptoms and mildly raised troponins. A repeat ECG performed when the patient’s heart rate was lower showed resolution of the widespread T wave inversion.

Opinions were sought from a multidisciplinary team consisting of a haematologist, a cardiothoracic surgeon, an infectious disease specialist and two radiologists. The main differentials for this patient included lymphoproliferative disease, germ cell tumour, thymic neoplasm or disseminated TB. A tissue biopsy of the anterior mediastinal mass was crucial for diagnosis and treatment. Hence the patient underwent a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical biopsy of the anterior mediastinal mass, which revealed frank pus within the mass. Histological examination was consistent with thymic tissue with necrotising granulomatous inflammation with absence of malignant changes. A tissue and pus acid-fast bacilli culture isolated mycobacterium TB complex. Hence, it was conclusive that this patient had disseminated TB, which is defined by the presence of two or more non-contiguous sites (lung, thymus, cardiac) resulting from haematogenous dissemination of mycobacterium TB.4

The patient was started on 9 months of anti-TB chemotherapy with 3 months of a tapering course of oral prednisolone. Subsequent clinical management for consideration included pericardiectomy if there were no signs of improvement. After 6 weeks of treatment, a repeat cardiac MRI showed complete resolution of constrictive physiology (Supplementary Video 2) and significant reduction in pericardial thickness (Figure 4B). A subsequent chest CT scan 3 months into treatment revealed near complete resolution of the anterior mediastinal mass, regression of mediastinal adenopathy and smaller right upper lobe nodule, with a significant reduction in pericardial thickening (Figure 5B). Before initiating the anti-TB chemotherapy and oral steroids, a repeat ECG was performed (Figure 1B) when the patient’s heart rate was lower and it showed resolution of the widespread T-wave inversion, especially in leads V3–V6. This showed that the patient’s initial widespread T wave inversion on presentation was likely to have been related to his tachycardia.

In addition, the patient was referred to an immunologist to exclude rare primary immunodeficiencies as he was negative for retroviral infection and there was no strong contact history for TB infection among close contacts such as family members in the same household or work colleagues.

Discussion

Based on a literature review, this is the first case of tuberculous constrictive pericarditis in Singapore demonstrating resolution of constrictive physiology after treatment initiation.

A Multimodality Imaging Approach for Diagnosis of Constrictive Pericarditis

Diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis involves a multimodality imaging approach. Echocardiography is usually the first-line diagnostic tool for these patients. Echocardiographic hallmarks include bounce of the ventricular septum, with the septum shifting toward the left ventricle with inspiration, a reduction in mitral E velocity in the first beat of inspiration by usually more than 25% compared to the first peak expiratory E velocity, a reduction in the tricuspid E velocity in the first beat of expiration by more than 40% compared with the first peak inspiratory E velocity, increase of diastolic flow reversal in the hepatic vein with expiration and preserved or increased tissue Doppler-derived early diastolic mitral annular velocity (e′), with the lateral e′ frequently being lower than the medial e′ (annulus reversus).

CT and cardiac MRI are frequently used as second-line imaging modalities in patients with signs of constriction. CT may, among others, accurately assess pericardial thickness and detect the presence, extent and localisation of calcification within the pericardial space. Cardiac MRI may also detect pericardial thickening and is able to assess the presence and extent of pericardial inflammation. Functional alterations, such as respirophasic variation in septal motion, may additionally be shown by cardiac MRI using cine sequences.5 This patient had all the pertinent features of constrictive pericarditis on his echocardiogram, cardiac CT and cardiac MRI.

Current Treatment Guidelines on Tuberculous Constrictive Pericarditis and Controversy

The patient was initiated on guideline-directed therapy for tuberculous constrictive pericarditis.4 Six months of anti-TB chemotherapy is a class 1 recommendation for TB pericarditis. This patient was started on daily doses of rifampicin 600 mg, isoniazid 300 mg, ethambutol 1,000 mg, pyrazinamide 1.5 g and pyridoxine 20 mg for 2 months. He was then switched to the same dosages of rifampicin, isoniazid and pyridoxine for 7 months. While continuation beyond a 6-month period potentially increases the risk of adverse side-effects with limited gain in benefits, it was decided to extend TB treatment beyond 6 to 9 months in view of the high burden of disease. The patient was also started on an additional 11 weeks of a tapering dose of oral prednisolone: 60 mg for 4 weeks; 30 mg for 4 weeks; 15 mg for 2 weeks; then 5 mg for 1 week. This is a class 2b indication based on European Society of Cardiology guidelines.6

Pericardiectomy for symptomatic treatment is a class 1 recommendation and would be considered in the event of no improvement after 4–8 weeks of medical therapy. Pericardiectomy, however, is costly, invasive and associated with a mortality rate of 6–12%.7

The efficacy of concomitant steroid therapy during anti-TB treatment remains controversial. Several studies of patients with tuberculous constrictive pericarditis have concluded that tuberculostatic treatment combined with steroids might be associated with fewer deaths and a less frequent need for pericardiocentesis or pericardiectomy, although these differences were not statistically significant.3,8 However, in a retrospective observational study by Kim et al. in 2020, it was demonstrated that more than 80% of patients with tuberculous constrictive pericarditis showed complete resolution of restrictive physiology on echocardiogram after 6 months of anti-TB chemotherapy and 3 months of steroids.9 Our patient described in this case study would have been classified as a responder to both anti-TB and steroid therapy.

While further prospective image-guided studies are required, both the Korean study and our case report point to suggestions for steroid therapy and potentially an upgrade in recommendations for steroid therapy in future guidelines involving treatment of tuberculous constrictive pericarditis.

Approach to Patients with Anterior Mediastinal Mass and Rarity of Tuberculous Thymus

The classic mnemonic for the differential diagnosis of anterior mediastinal mass is the proverbial 4 Ts – thymoma, teratoma, ‘terrible’ lymphoma and thyroid – and obtaining a histological and bacteriological confirmation of the aetiology of the anterior mediastinal mass was fundamental before starting therapy.10

TB of the thymus or the anterior mediastinum is an extremely rare cause of anterior mediastinal mass. Only 15 cases of thymic TB have been reported in the literature in the past 7 decades worldwide.8 It has been suggested that thymic TB in infants and children is most likely primary TB, unlike in adults, where it represents remnants of post-primary localised mediastinal TB.11,12

Immunity Status of Patients with TB Constrictive Pericarditis

It is important to determine the retroviral status of patients with tuberculous constrictive pericarditis as steroids should be avoided in HIV-associated tuberculous pericarditis due to the increased risk of malignancy.3,6 This patient was retroviral negative and had no other apparent risk factors for TB such a strong contact history. Hence, despite not being recommended in any guidelines, the patient was referred to an immunologist to exclude primary immune deficiency diseases.

Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases is an inherited disorder that causes genetic defects in the mononuclear phagocyte/helper T-cell pathway, resulting in a defect in the interferon-gamma and interleukin-12 pathway. It increases the risk of mycobacteria infection including TB and fungal infections.13

The other condition – anti-interferon-γ antibody – is a rare cause of adult onset immunodeficiency leading to disseminated mycobacterial infection, but typically non-TB mycobacteria rather than Mycobacteria tuberculous.14

Conclusion

In this rare case of tuberculous constrictive pericarditis due to disseminated TB there was a dramatic response to partial treatment with anti-TB chemotherapy and steroids. While tuberculous constrictive pericarditis is traditionally thought to be irreversible, based on our experience and a recent retrospective observational study, it can be responsive to anti-TB chemotherapy and steroids. The initial approach for patients who present with anterior mediastinal mass requires a multidisciplinary and multimodality approach and a consideration of the more common differentials, the 4Ts, histological examination and confirmation is critical before starting therapy. Last, while not directed by guidelines, it may be prudent to refer patients with disseminated TB with no apparent risk factors for TB to an immunologist to exclude primary immune deficiency disease, such as Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases and anti-interferon-gamma antibody.

Clinical Perspective

- Constrictive pericarditis is rarely caused by tuberculosis (TB) in developed countries. The current class 1 recommendation for treatment of tuberculous constrictive pericarditis is anti-TB chemotherapy and pericardiectomy, should medical therapy fail.

- Multimodality and multidisciplinary approaches are required for the diagnosis and management of tuberculous constrictive pericarditis from disseminated TB and patients who present with anterior mediastinal mass.

- Current guidelines only have a class 2b recommendation for steroid therapy due to lack of strong evidence showing efficacy in treatment. As with this case, a recent retrospective observational study showed high rates of reversibility of constrictive pericarditis with steroid therapy, indicating that timely steroid and anti-TB chemotherapy can obviate the need for pericardiectomy.

- Further prospective imaging-guided studies are required for future guidelines for the treatment of tuberculous constrictive pericarditis to have a stronger evidence base for steroid therapy.

- It may be prudent to refer patients with disseminated tuberculosis with no apparent risk factors for tuberculosis to an immunologist to exclude primary immune deficiency disease, such as Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases and anti-IFN-γ autoantibodies.