Paravalvular regurgitation is a known complication in 5–17% of prosthetic valve replacements, and may be treated with either surgery or percutaneous repair in patients with refractory heart failure and/or haemolytic anaemia.1 Percutaneous paravalvular leak (PVL) closure is supported by a class 2a recommendation in the 2020 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) valvular heart disease guidelines, and has been shown to improve functional class and decrease mortality.2,3–5 However, tricuspid PVLs are uncommon and experience with tackling such cases limited, with few case reports in the literature and multiple variations in the techniques used.6–9 We aim to discuss the step-by-step methodology and technical considerations for percutaneous tricuspid PVL closure using a case as a practical illustration.

Case Report

Our patient was a 67-year-old man with rheumatic heart disease treated with a Björk–Shiley aortic valve replacement in the 1980s, and subsequent Carbomedics mitral valve replacement and St Jude tricuspid valve replacement in the 1990s. In addition, he had a significant cardiac history of coronary artery disease and AF and a pacemaker had been inserted for sick sinus syndrome. He presented with right heart failure secondary to severe tricuspid PVL.

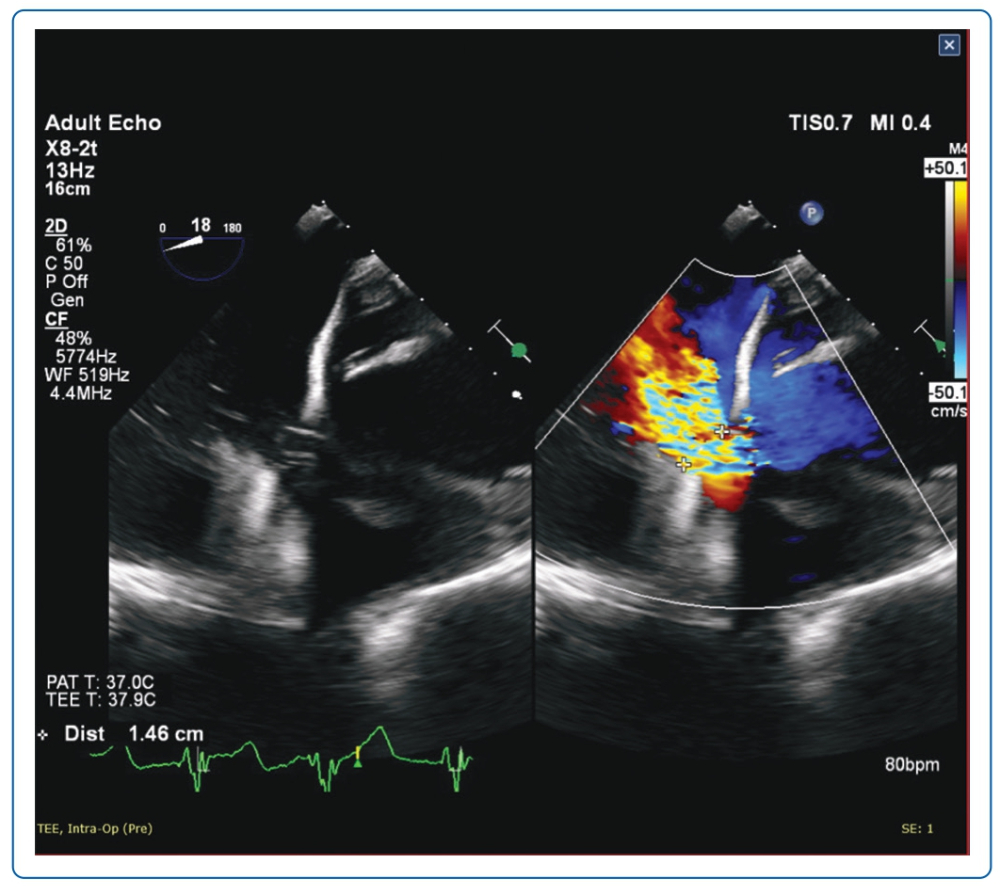

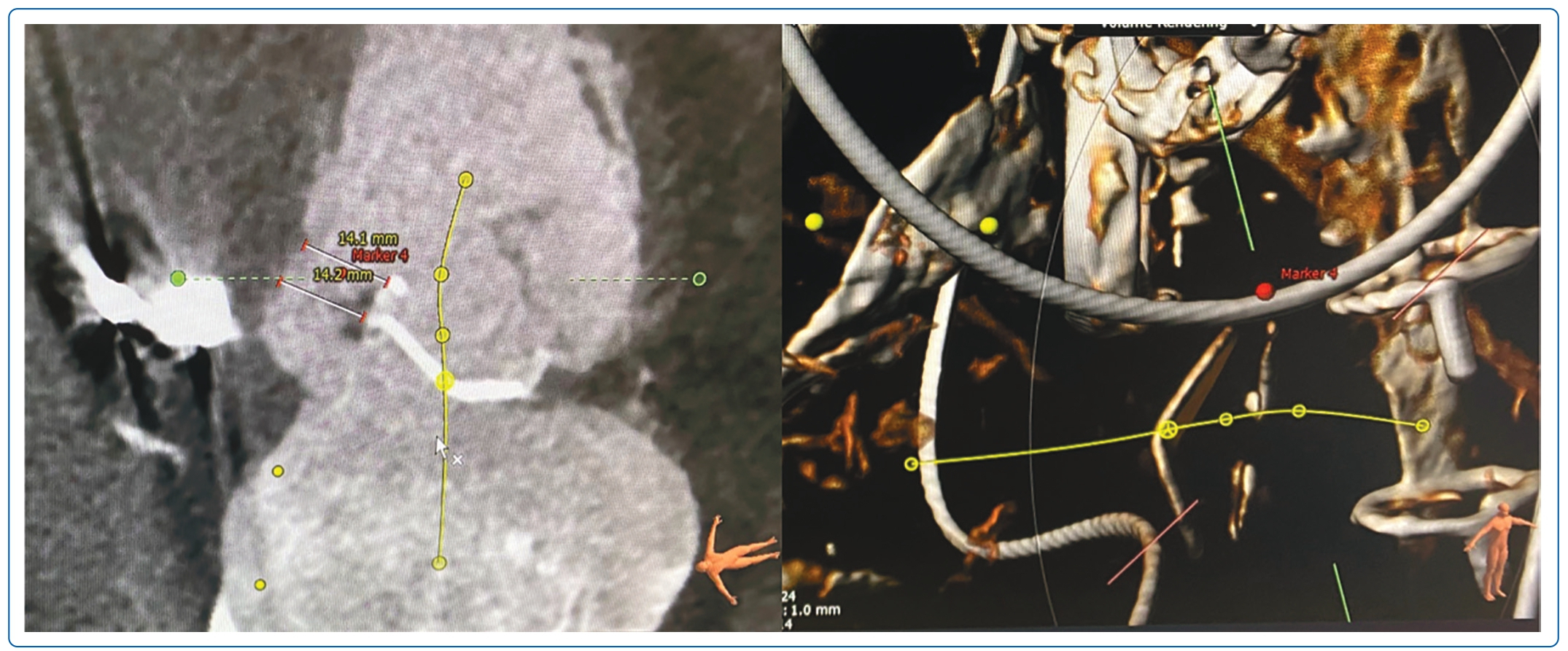

Transoesophageal echocardiogram (TOE; Figure 1) and CT scan (Figure 2) showed severe PVL through a 15 × 13 mm defect at the tricuspid valve medial aspect. The CT scan also identified the optimal fluoroscopic crossing angle to guide the procedure. After discussion with the Heart Team, he was deemed too high risk for a third redo sternotomy and surgical repair, thus the decision was made for percutaneous repair, in accordance with a class 2a recommendation in the 2020 ACC/AHA valvular heart disease guidelines.2

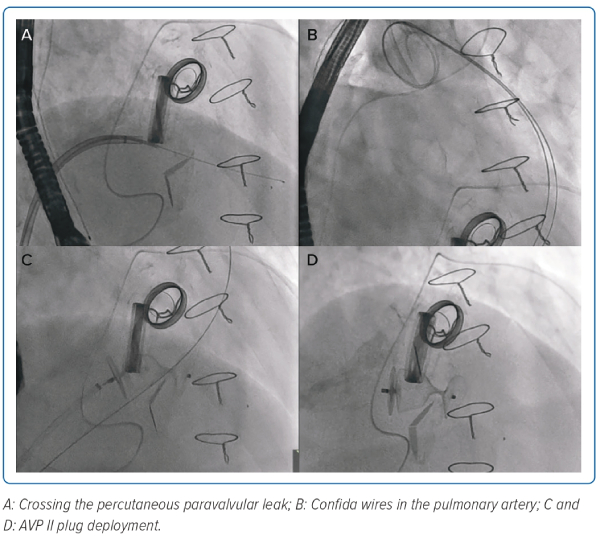

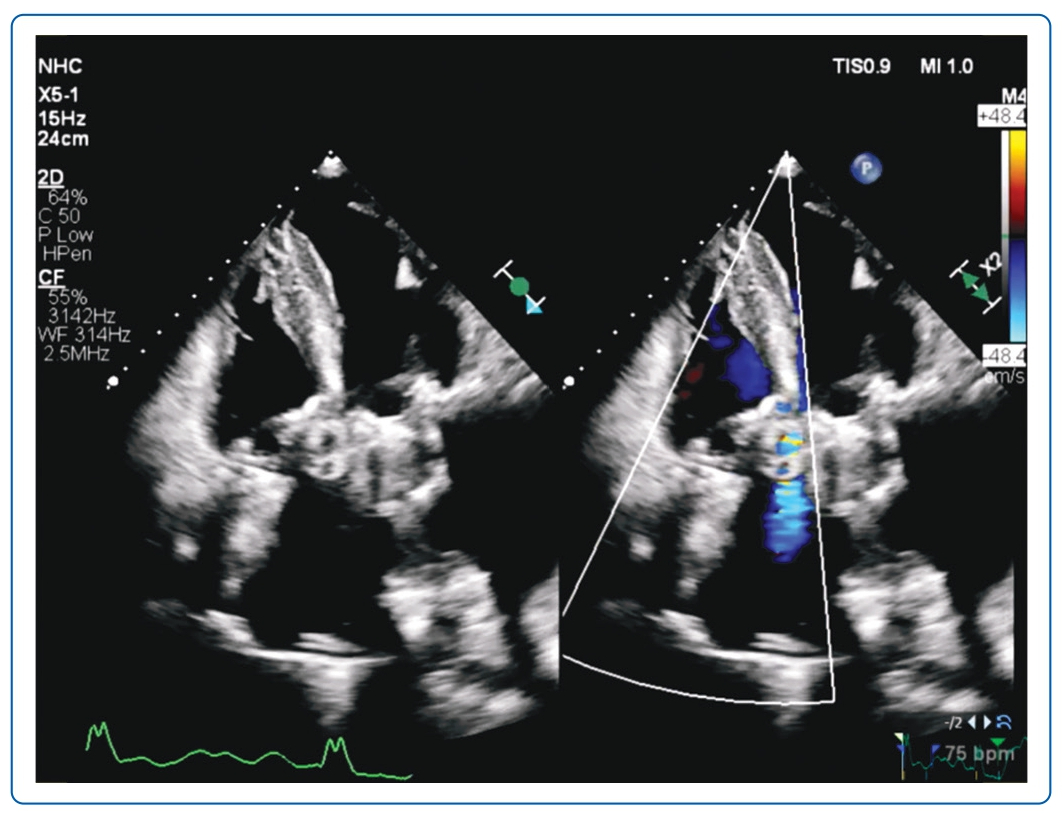

A 20 Fr right femoral venous access was obtained and pre-closed with two Perclose ProGlides (Abbott). The PVL was crossed using the CT pre-determined fluoroscopic angle with an Agilis (Abbott) sheath and telescoping 5 Fr multipurpose catheter (Figure 3A). The Terumo glidewire (Terumo) was exchanged for a Confida pigtail wire (Medtronic). The Confida wire initially provided inadequate support when placed in the right ventricle (RV), and thus was repositioned to the pulmonary artery (PA; Figure 3B). A second Confida wire was introduced to maintain access across the PVL. A 20 mm Amplatzer Vascular Plug II (AVP II) plug was introduced via a 7 Fr Shuttle sheath and deployed (Figure 3C). The second Confida wire was removed and the AVP II plug was released (Figure 3D) after confirmation of reduction in PVL, device stability and no impedance of mechanical valve function on TOE and fluoroscopy. Repeat transthoracic echocardiogram 6 months later showed significant improvement with mild residual PVL (Figure 4, Supplementary Videos 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Discussion

There are several important clinical considerations highlighted for this complex procedure. Firstly, the use of imaging (CT and 3D TOE) was crucial.10 These allowed for more accurate determination of the PVL site for crossing and dimensions for ideal sizing. A combination of the predetermination of the optimal fluoroscopic angle for crossing by CT and 3D TOE also allowed precise catheter positioning for ease of traversing the PVL. Where available, the use of hybrid fusion imaging (fluoroscopy, TOE, CT) may further facilitate the performance of the procedure. Secondly, the use of a 20 Fr right femoral venous sheath allowed for the simultaneous deployment of two plugs if necessary. The access site was also preclosed with Perclose to allow for better haemostasis post-procedure. Thirdly, the placement of the Confida wire in the PA instead of the RV provided increased support for introduction of the various catheters and devices. In rare cases, a veno-venous loop technique can also be used for added support as described by Pu et al.6 Additionally, introducing the second Confida wire helped maintain access across the PVL to avoid the difficulty of recrossing the PVL should the need arise. Lastly, it is imperative to confirm device stability and no device interaction with the mechanical valve leaflets both on fluoroscopy and TOE before release.

Conclusion

This case highlights the challenges faced and provides clinical pearls in dealing with percutaneous tricuspid PVL closure. -web-resources/image/1.png)

Clinical Perspective

- Using CT and 3D transoesophageal echocardiography allowed determination of the percutaneous paravalvular leak site and size and, in particular, for CT, the optimal fluoroscopic angle for crossing.

- Using a 20 Fr right femoral venous sheath allowed for the simultaneous deployment of two plugs if necessary.

- Placing the Confida wire in the pulmonary artery instead of the right ventricle provided improved support for the introduction of catheters and devices. Additionally, introducing the second Confida wire helped maintain access across the percutaneous paravalvular leak.

- It is imperative to confirm device stability and no device interaction with the mechanical valve leaflets on fluoroscopy and transoesophageal echocardiography before release.