Heart failure (HF) has an estimated global prevalence of 1–2% of the adult population and the reported prevalence in Asia is slightly higher, at 1–3%.1–3 In-hospital mortality rates range from 2% to 9.2% across the region, and reported 30-day mortality ranges from 1% in Malaysia to as high as 17% in Indonesia.3–5 The wide range of outcomes may be due to several factors, including social variations and disparities in the income levels of countries, standards of care, the availability and accessibility of early diagnosis, optimal disease-modifying medical treatments, and advanced interventions in the management of HF.3–5 Although systematic reviews have already been conducted to elucidate the epidemiology, patterns of management and outcomes of patients with HF in the Asia-Pacific region, information about the availability and accessibility of diagnostics and treatments for HF, as well as the performance measures of quality of care for HF in the region, is lacking. Hence, the aim of this study conducted by the Asian Pacific Society of Cardiology (APSC) was to describe the gaps in the diagnosis and treatment of HF in the APSC member countries via an online survey.

Methods

Study Design and Survey Questionnaire

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted among medical professionals practising in member countries of the APSC who provide care to patients with HF. The study participants answered an English online self-administered questionnaire containing items that assessed baseline characteristics, opinions on management gaps in HF, estimates of rates of the availability and usage of diagnostic tests and treatment options, and other performance metrics of quality of care for patients with HF. All items were multiple choice, with some questions allowing more than one response. Five cardiologists from Singapore reviewed the items on the questionnaire and indicated their decision to remove, keep, or modify each item. A questionnaire item was considered final by consensus.

Procedure and Study Population

The survey ran from May to September 2022. An invitation to participate in the study was advertised on different social media platforms and distributed to member cardiac societies of the APSC for distribution to their members via email. Selection bias was minimised by distributing the questionnaire to various online platforms to improve visibility. The interested respondents were directed to the online questionnaire. Only eligible respondents who completed the questionnaire were included in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for all variables of interest. Data are presented as the mean with SD, or as frequency with proportion for quantitative and qualitative variables, respectively. Variables investigated included country of practice, speciality, type of institution, perceptions of gaps in the diagnosis and treatment of HF, availability of diagnostic modalities and pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for HF, usual length of hospital stay of patients with HF, availability of in-hospital education, and the availability of post-discharge care. All analyses were tabulated in Excel.

Results

The study involved 257 respondents from 26 countries or regions, most of which were member countries or regions of the APSC. India and Indonesia had the most respondents (Table 1). Forty-four per cent of respondents were cardiologists who were non-HF specialists, while 28% were HF specialists. The majority (64%) practised in tertiary hospitals or regional referral centres.

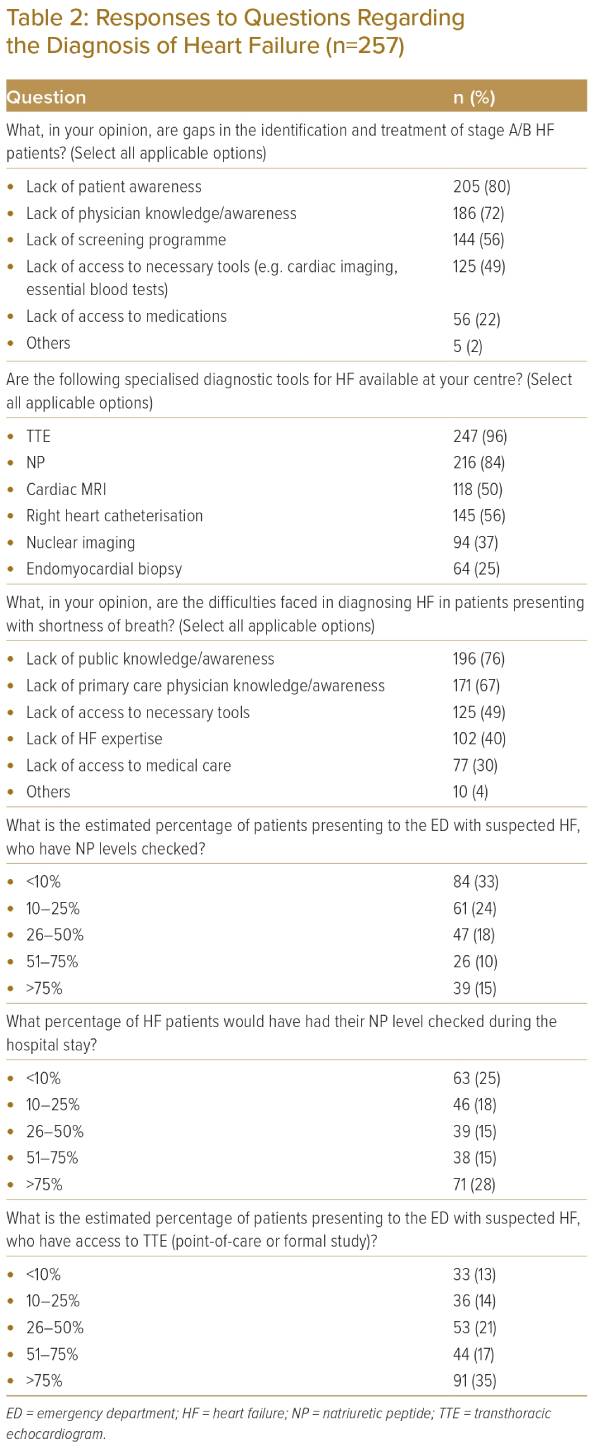

The most commonly mentioned gaps in the identification and treatment of stage A/B HF patients were the lack of patient awareness (80%) and physician knowledge/awareness (72%; Table 2). The most commonly mentioned difficulties faced in the diagnosis of HF in patients presenting with shortness of breath were the lack of public knowledge/awareness (76%) and the lack of primary care physician knowledge/awareness (67%). Regarding the use of diagnostic tests, the following survey findings were noted:

- Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE; 96%) and natriuretic peptide (NP; 84%) were the most commonly mentioned specialised diagnostic tools for HF available at their respective centres.

- Just over half (52%) responded that more than 50% of their patients had access to TTE.

- Many respondents (56%) estimated that 25% or less of the patients presenting to the emergency department with suspected HF had NP levels checked.

- The majority (58%) responded that 50% or fewer of their patients would have NP levels checked during the hospital stay.

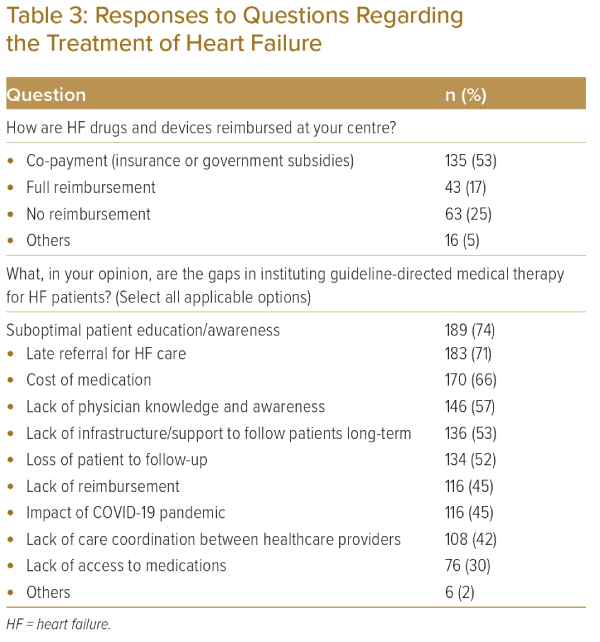

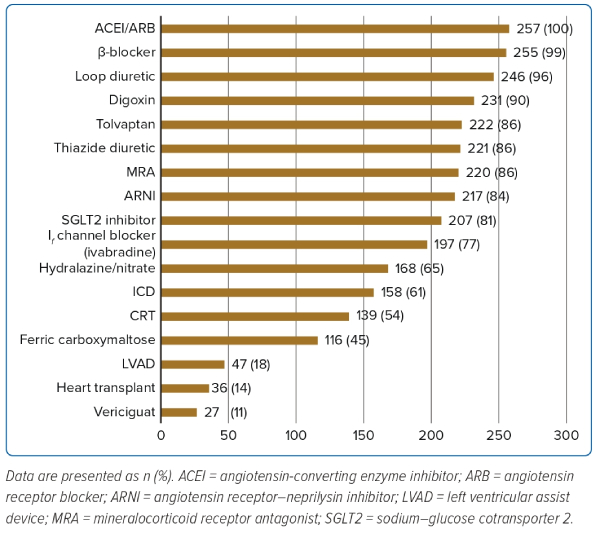

Among the therapeutic options for HF, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) were the most commonly reported available treatment (100%), followed by β-blockers at 99% and loop diuretics at 96% (Figure 1). For mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), angiotensin receptor–neprolysin inhibitors (ARNIs) and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2Is), the proportion of respondents with access was 86%, 84% and 81%, respectively. The majority (53%) reported that HF medications and devices were reimbursed with co-payments while 25% reported no reimbursement and 17% reported full reimbursement. The majority of respondents mentioned the following gaps in instituting disease-modifying medical therapy: suboptimal patient education/awareness (74%), late referral for HF care (71%), cost of medication (66%), lack of physician knowledge and awareness (57%), lack of infrastructure/support to follow patients in the long term (53%), and loss of patients to follow-up (52%) (Table 3).

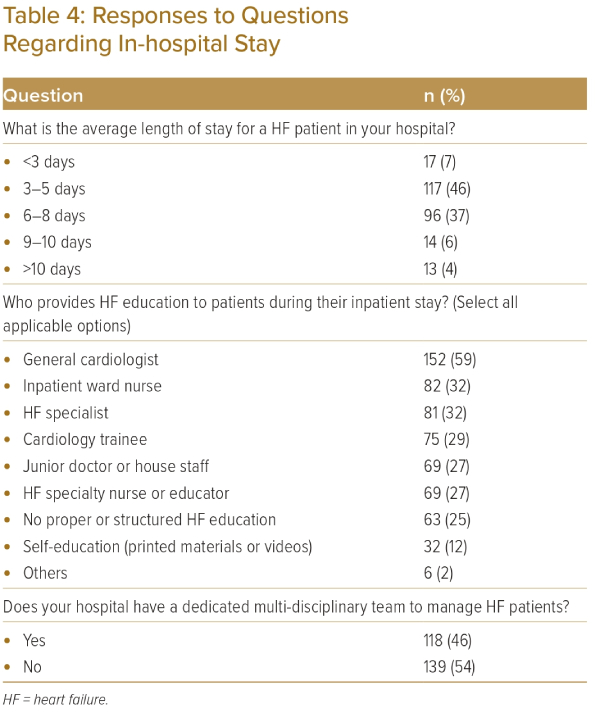

Most of the respondents reported that HF patients stayed in the hospital for 3–8 days (46% responded 3–5 days and 37% reported 6–8 days) (Table 4). Just over half (54%) reported that their institution had no multidisciplinary team for HF. Furthermore, 60% of respondents noted that HF education was conducted by physicians (cardiology trainees, junior physicians or house staff, general cardiologists and HF physicians).

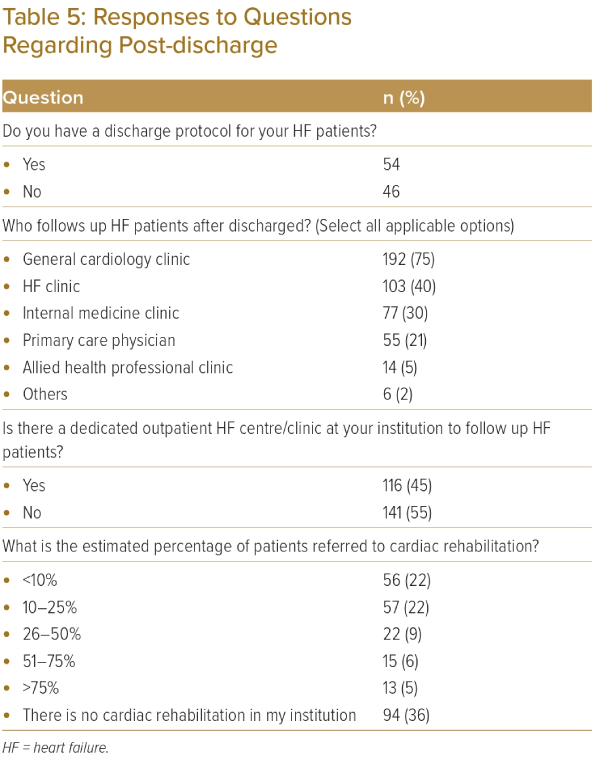

Just over half of the respondents (54%) had a discharge protocol but had no dedicated outpatient HF centre or clinic at their institution to follow up HF patients (55%) (Table 5). The availability of cardiac rehabilitation was also limited.

Discussion

This online survey shows that healthcare professionals in the APSC member countries perceive substantial gaps in the diagnosis and management of HF in their areas of practice. The majority reported that most of their patients with HF have not undergone NP testing, an important test for the diagnosis of HF.6–9 The most accessible and available diagnostic tool was TTE. Among the therapeutic options for HF, ACEIs or ARBs and β-blockers were readily available but MRAs as well as newer and relatively more expensive agents such as ARNIs and SGLT2Is are less available. Gaps in post-discharge care were also identified, namely the lack of a discharge protocol, a dedicated outpatient HF centre or clinic for HF follow-up, and low access to cardiac rehabilitation.

In the Asia-Pacific region overall, HF is usually a clinical diagnosis.5 This is no surprise, given the results of this survey showing the non-universal access to TTE and the low availability of NP. However, the APSC consensus statements on the diagnosis and management of chronic HF recommend that all patients with suspected HF should have their NP levels checked (with N-terminal pro-B-natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP]) and undergo TTE, together with a chest X-ray and an ECG.10 The consensus also noted that a plasma NT-proBNP concentration <125 pg/ml or BNP <35 pg/ml makes a diagnosis of HF unlikely, but if NP testing is not available, TTE may be used to diagnose HF. TTE, although not the diagnostic gold standard, provides useful information on cardiac function such as left ventricular ejection fraction, chamber size, eccentric or concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, regional wall motion abnormalities, right ventricular function, pulmonary hypertension, valvular function and markers of diastolic function.11,12

Several studies have reported similar results concerning low NP use. Data from the Indian College of Cardiology National Heart Failure Registry found that only 29% of HF patients had biomarker data and this limited usage was attributed to socioeconomic factors.13 In the ADHERE-AP registry, only 7.8% and 8.5% of patients hospitalised for acutely decompensated HF (ADHF) had BNP and NT-proBNP measurements, respectively.14 Use of TTE was higher and left ventricular function was assessed in approximately one-half of patients.14 In the Korean HF registry, 76.6% and 79.8% of patients hospitalised for ADHF were assessed for NP levels or left ventricular function, respectively, to support a clinical diagnosis.15 In Australian primary care clinics, TTE was performed in approximately 22% of patients with suspected HF but the rate increased to 64% after a diagnosis of HF was already made.14

While the availability of ACEIs or ARBs, β-blockers and loop diuretics was acceptable, there was a substantial gap in the availability of MRAs, SGLT2Is and ARNIs. The APSC consensus statements recommend an ARNI (preferred)/ACEI/ARB, a β-blocker, an MRA and an SGLT2I for all patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) unless contraindicated; these standard disease-modifying medical treatments should be instituted as soon as possible and uptitrated every 2–4 weeks to target or to the maximally tolerable dose in 3–6 months. These agents are also treatment options for patients with HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction, although with a weaker strength of recommendation, whereas patients with HF with preserved ejection fraction should receive an SGLT2I and ARB/ARNI, and an MRA may also be considered, according to these APSC consensus statements.

Asian data from a systematic review had similar trends of higher use of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors (52–90%), which are generally lower than the rates in Europe (89%). The use of β-blockers ranged from 32% to 78% (versus 87% in Europe).3 The majority of patients received diuretics (76–99%) and 19–53% were prescribed digoxin. An Australian study of 1.93 million adults attending primary care showed that HF guideline-based therapy remains suboptimal, and the proportion of eligible patients receiving optimal treatment for HFrEF is relatively low.16

A more recent literature review reported rates of RAAS inhibitors ranging from 51% to 75%, which were lower than those from ADHERE (83%), EHFS II (80%) and UKNHFA (91%).5 The use of β-blockers from ASIAN-HF (79%) and INTERCHF (61%) was similar to western studies (61–86%). The review also reported a low use of aldosterone antagonists (19–53%), similar to western data, and noted that there was a preference for spironolactone due to the lack of regulatory approval of eplerenone in many countries in the region and probably the high cost in countries where it is available.5

Our survey found that HF patients stayed in the hospital for 3–8 days (45.5% responded 3–5 days and 37.4% reported 6–8 days). These aligned with rates reported in the Reyes et al. study, in which the median length of stay ranged from 5 to 9 days across the region (versus 8 days in Europe and 5 days in the United States).3 Our survey also found that during admission, HF education was largely the burden of physicians; this could be an area of improvement by allowing more nurses and allied healthcare professionals to educate patients and by maximising the use of digital and printed media. Such education interventions have been shown to deliver quality improvements (e.g. higher rates of guideline-directed medical therapy at discharge and discharge process care measures, including diet counselling, weight monitoring instructions, and scheduling of outpatient clinic follow-up).17

Multiple gaps were also identified in the long-term care of patients (e.g. poor follow-up and access to cardiac rehabilitation), and this was also reported in other studies.18 These gaps were also reflected in the respondents’ opinions on the gaps in instituting disease-modifying medical therapy, wherein lack of infrastructure and support to follow up patients in the long term (10.5%) and loss of the patient to follow-up (10.1%) were among the most commonly mentioned. The other gaps mentioned were suboptimal patient education/awareness, the cost of medication (13.3%), and the lack of physician education/awareness (11.4%). It is important to address these gaps because these can adversely affect treatment adherence and long-term patient outcomes. Addressing these gaps would need collaboration with multiple sectors, including health ministries, payers and insurers, healthcare institutions across all levels of care, and the community.

The reader should be aware of the limitations of the study. These include the underrepresentation of many countries, with the majority of the respondents coming only from four countries, namely India, Indonesia, Singapore and Australia (n=137, 53%). These four countries alone vary largely in terms of economic development, healthcare systems, policies and financing structures, and similar variations are observed in the other participating countries. There is also heterogeneity between the public and private sectors in the participating countries. These variations may limit the generalisability of the study results. The study also used an online survey that asked respondents about their opinions and personal estimates of quality-of-care performance; these may deviate from the actual rates in their institutions and may introduce recall bias.

The authors also acknowledge that highlighting and quantifying the gaps in HF management would be insufficient to develop concrete solutions to address these gaps. Qualitative responses would have been helpful to identify the specific challenges faced by each APSC member country, which vary widely across various aspects, as previously mentioned. Nonetheless, with these findings, we encourage the various APSC member countries to conduct qualitative studies and quality improvement initiatives on HF management. Several quality improvement tools and programmes have already been initiated in the Asia-Pacific region from which the APSC member countries can adopt or build upon.17,19–21

Conclusion

This study found that healthcare professionals in the APSC member countries perceived substantial gaps in the availability of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions for HF in their areas of practice. NP testing was less available than TTE, which is the primary diagnostic modality for HF in the region. MRAs and newer but more expensive disease-modifying medical therapies such as ARNIs and SGLT2Is were also not available in many centres. Furthermore, many centres in the region reported gaps in the post-discharge care of patients with HF.

Clinical Perspective

- Clinicians treating patients with heart failure (HF) in the Asia-Pacific region identified substantial gaps in the management of HF.

- These gaps include poor access to important diagnostic tests (such as natriuretic peptide testing) and treatments (>10% with no access to mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors).

- These gaps should be addressed to ensure that patients with HF receive appropriate long-term care to optimise patient outcomes.