Non-compaction cardiomyopathy (NCC) is a genetic condition that occurs due to arrested development in embryogenesis. According to the American Heart Association, NCC is classified as primary genetic cardiomyopathy involving predominantly the distal portion with deep intertrabecular recesses.1 Non-compaction has been categorised as unclassified familial cardiomyopathy because it is not clear whether this is separate cardiomyopathy or an acquired trait shared by many phenotypically distinct cardiomyopathies.2 NCC usually occurs in isolation or is associated with congenital or developmental disorders.3–5 Currently, the prevalence of NCC has not been entirely determined.6

We report a case of biventricular NCC in an adult male who presented with intermittent chest pain.

A 61-year-old man, without known coronary risk factors, presented at our hospital with a 1-year history of chest pain and progressive easy fatigability accompanied with bipedal oedema of 3 months duration. He reported no palpitations, orthopnoea, syncope, febrile episodes or productive cough. Family and personal social history are unremarkable. Clinical examination showed no cardiorespiratory distress, a pulse rate of 77 BPM, a blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg and normal jugular venous pressure of 8 mmHg above the sternal angle. He had an irregular heart rate with no murmur, rubs or gallops, and has clear breath sounds. His extremities did not show any oedema.

The electrocardiogram showed AF in a controlled ventricular response with a ventricular ectopic beat (QRS duration of 0.08 seconds with QTc interval of 0.42 seconds). There were no ST-T segment shifts or ischaemic changes. His 2D echocardiography showed normal left ventricular wall geometry (mass index of 70.9 g/m2 and relative wall thickness of 0.27) with hypokinesia of the inferior wall from base to apex with an ejection fraction of 44.9%, and grade I diastolic dysfunction; the atria were dilated (left atrial volume index of 42.1 ml/m2, right atrial volume index of 39.1 ml/m2); the right ventricle had a normal dimension with adequate contractility; and there was mild pulmonary hypertension with a pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 40 mmHg (Supplementary Videos 1 and 2).

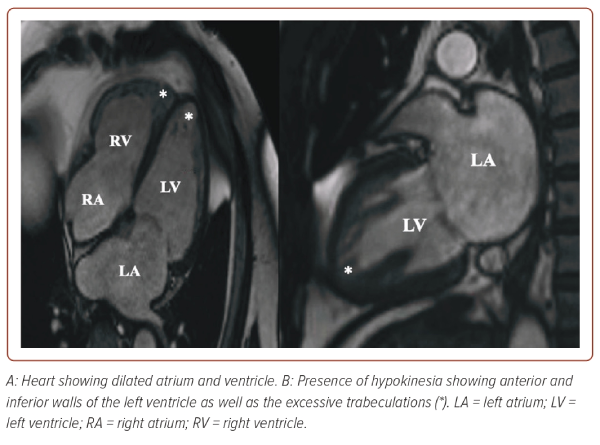

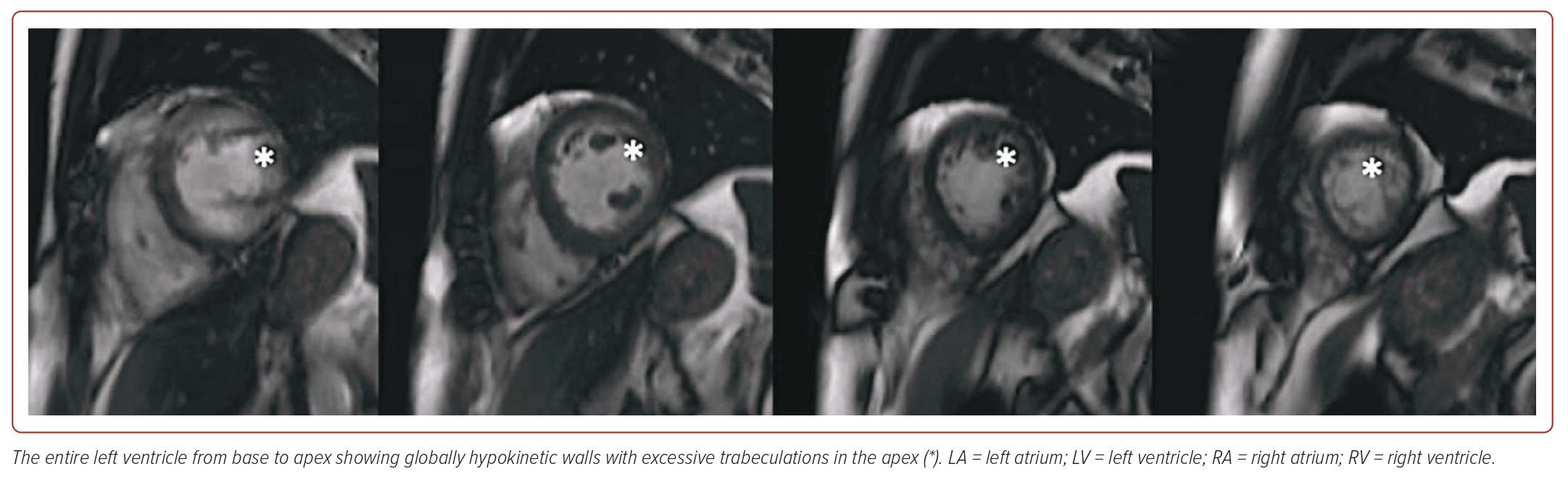

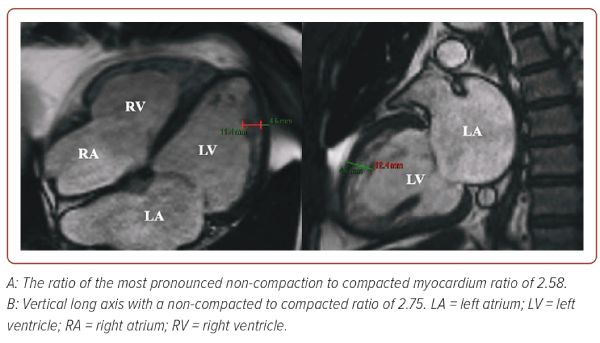

The patient underwent a coronary angiogram, which revealed normal coronary arteries. Cardiac MRI (CMRI) confirmed a dilated left ventricular cavity with global hypokinesia, reduced systolic function (calculated ejection fraction of 41%), and excessive trabeculation in the midventricular to apical segments, with a non-compacted to compacted ratio of 2.58. There was also cavity dilation in the right ventricle with hypokinesia, reduced systolic function, and excessive trabeculation in the apical segment (Figures 1 and 2). The patient was referred to an electrophysiologist and started on anticoagulation and possible cardioversion. Subsequently, he was stable throughout the hospital stay and was discharged with the following medications: carvedilol, losartan, rosuvastatin, trimetazidine, and clopidogrel, and the patient adhered to these.

Discussion

The characteristic of NCC is a compacted epicardial layer with a loose, interwoven meshwork and prominent trabeculations and recesses that occur due to arrested compaction during early embryogenesis.7 The prevalence of biventricular NCC is not well studied because it is an uncommon condition. Apart from lack of knowledge, the similarity of NCC to other diseases of myocardium and endocardium may also cause the rarity of this condition.3

Several genetic studies have postulated the association of NCC with other cardiomyopathies and may have one common genotype but have highly variable phenotypic expression.3,8 Hence, physicians still have uncertainties regarding whether non-compaction can be regarded as an isolated entity or as one of the traits of other cardiac diseases or complex syndrome.9 As demonstrated in this case, our patient had biventricular non-compaction associated with left ventricular dilation with significant systolic dysfunction.

The most common form of non-compaction non-completion involves only the left ventricle since the ventricular apex is usually the last segment to complete the compaction process. However, with normal morphogenesis, the termination of myocardial maturation may lead to several extensions of non-compaction. Only a few studies have reported that less than half of patients involve the right ventricle.10–12 There is still no specific criterion to diagnose right ventricular non-compaction.

As previously described, the diagnosis of ventricular non-compaction is usually made through 2D echocardiography and CMRI although currently there are still no universally accepted diagnostic criteria. Use of these diagnostic tests primarily evaluates the thickness between compacted and non-compacted myocardial layers and the degree of myocardial fibrosis.10 However, for 2D echocardiography, the apical region cannot be fully assessed, which leads to underestimation of the degree of non-compaction. Hence, CMRI has been an imaging choice to confirm or rule out NCC because it gives a more detailed description of the cardiac morphology. A ratio of compacted to non-compacted myocardium >2.3 produces the highest sensitivity (86%) and specificity (99%).12 Several CMRI criteria are used based on linear measurements at end diastole (Petersen method), end systole (Stacey method), mass ratio between total and trabeculae mass (Jacquier method) or fractal dimension (Captur method).13 For this patient, we used the Petersen criteria wherein the ration of the NC to compacted myocardium was measured at the most pronounced trabeculations perpendicular to the solid myocardium using long axis steady-state free precession cine images (Figure 3).

In a study conducted by Rocon et al., a combination of 2D echocardiography and CMRI increases the diagnosis of biventricular NCC given the following variables: left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) by CMRI, right ventricular end-systolic volume (RVESV) by CMRI, right ventricular systolic dysfunction (RVSD) by 2D echocardiography, and right ventricular lower diameter (RVLD) by CMRI providing accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity rates of 75.5, 77, 75%, respectively.12

To the best of our knowledge, there is no specific criterion for diagnosing RVNC in the literature to date.

NCC displays a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations ranging from utterly asymptomatic individuals to severely reduced function, including congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, systemic venous thromboembolism and even death.7,9 The pathophysiological mechanisms of non-compaction remain uncertain.1 However, the development of systolic dysfunction may be attributed to impaired microvascular function causing subendocardial ischaemia. Diastolic dysfunction may be a result of abnormal relaxation and restrictive filling caused by prominent trabeculations.3,6,10 For arrhythmia, observed patterns ranged from AF to ventricular tachycardia.8

The management of biventricular NCC primarily depends on the clinical manifestation as there has been no specific treatment protocol.14 Patients with a reduced ejection fraction should be treated with standard medical therapy for heart failure. As demonstrated in this study, the presence of reduced systolic function with atrial fibrillation predisposes our patient to be high risk for our high patient risk of thromboembolism. The formation of thrombus may be due to local thrombi within the deep intertrabecular recesses.6,14

A study by Thavendiranathan et al. showed a low occurrence of thromboembolism (5% of the overall population; n=65) by administering warfarin for patients with NCC with ventricular dysfunction (LVEF <30%), atrial fibrillation, and previous history of embolic events with known ventricular thrombi.5,15

Annual ambulatory ECG monitoring is performed to assess arrhythmia, preventing the sudden risk of cardiac death.9 Neurological referral can also be appropriate as NCC usually involves other neurological disorders with manifestation such as stroke or seizure.10 Genetic counselling is recommended for family members for sudden cardiac arrhythmia risk stratification as part of the AHA guidelines.1 It consists of genetic history extending to at least three generations for follow-up of patients with NCC.5 However, this test is very costly in our current setting. Hence, echocardiographic screening is suggested.

Conclusion

Biventricular NCC is rare. However, non-compaction can be seen as a spectrum of phenotypic manifestations because it may be a form of cardiomyopathies. Although it is a rare type of cardiomyopathy, non-compaction should be considered a possible cause of anginal and heart failure events when more frequent aetiologies are excluded. A high index of suspicion for NCC is considered on the basis of heart failure symptoms and the absence of coronary artery disease. It causes arrhythmias, heart failure and predisposes to thrombus formation. The goal of therapy must depend on the clinical manifestation.

Clinical Perspective

- A high index of suspicion for non-compaction cardiomyopathy (NCC) is considered on the basis of heart failure symptoms and absence of an ischaemic cardiomyopathy.

- NCC causes arrhythmias, heart failure, and predisposes to thrombus formation. The goal of therapy must depend on the clinical manifestations.

- Biventricular NCC is rare. However, non-compaction can be seen as a spectrum of phenotypic manifestations because it may be a form of cardiomyopathies.

- Although it is a rare type of cardiomyopathy, non-compaction should be considered as a possible cause of anginal and heart failure events when more frequent aetiologies are excluded.